Courtney Handman and Divya Cherian discuss Occult Knowledge, AI, Secret Languages, Interoperability … and Owls

Strange powers accumulate at the interface of human and other-than-human life. We struggle to harness these powers. We use them, and we believe they are used against us. Great effort goes into channeling these liminal forces. Sometimes we call this effort “religion.” Sometimes it is “science,” “economy,” “politics,” or “art.” Often, we have no names for it at all.

In our October issue, two authors explore these motifs.

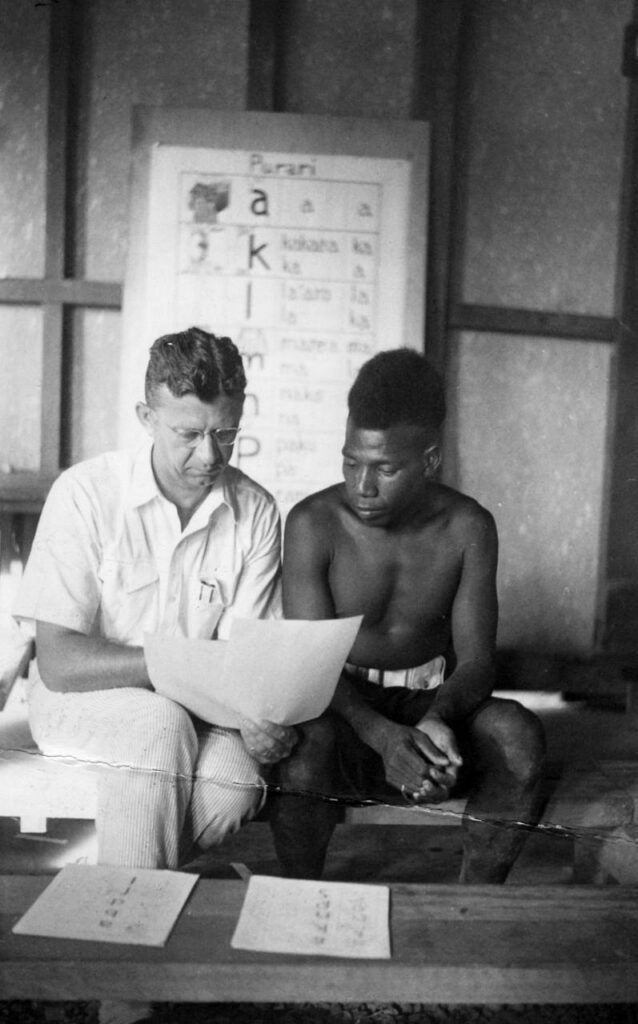

Courtney Handman. (2023). Language at the Limits of the Human: Deceit, Invention, and the Specter of the Unshared Symbol. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1-25. doi:10.1017/S0010417523000221

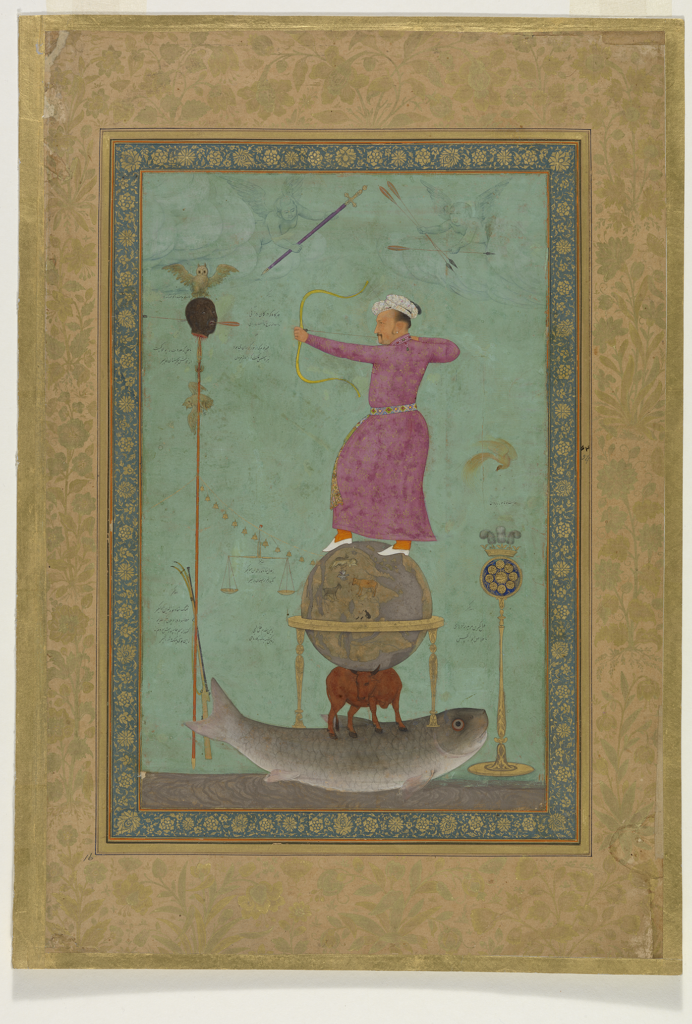

Divya Cherian. (2023). The Owl and the Occult: Popular Politics and Social Liminality in Early Modern South Asia. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1-28. doi:10.1017/S0010417523000245

The human fascination for things we cannot know or control is on vivid display in these papers. You will notice, across the many examples, how quickly people concoct stories about occult forces, new forms of intelligence, swirling techno-magical conspiracies, and odd creatures that flourish in the dark. The effect is numinous. And, at moments, a bit creepy.

For our editors, “secrecy” and “deception” are the strong threads connecting these essays. Here’s how they lay out the rubric.

CONCEALMENT, DECEIT, AND THE HUMAN

What is specific about humans? Johann Gottfried Herder thought religion was the uniquely human thing, while Heidegger was sure it was the ability to ponder one’s own Being. Ernst Cassirer supposed it was the capacity for self-fashioning. In a famous essay from 1906, Georg Simmel offered a more surprising response. He called the capacity for secrecy one of humanity’s greatest achievements since it requires the maintenance of interior mental worlds different from those of the immediate social and material context. Simmel was confident that deceit and occultation were distinctly human talents. Perhaps that assertion seems less secure now than it was in Simmel’s time, and for multiple reasons, not least the ambiguity of what exactly constitutes the human in a time when animal life, on one side, and artificial intelligence, on the other, push the bounds of humanness into an ever-narrower slot. Under this rubric, both contributions consider secrecy, deceit, and the occult: one considering artificial intelligence, the other taking up animal life.

Courtney Handman’s “Language at the Limits of the Human: Deceit, Invention, and the Specter of the Unshared Symbol,” uses an unexpected comparison to revisit the limits of the human by examining deceit and secrecy, or unshared language. She compares the language of Tok Pisin used by Christian converts in Papua New Guinea, and the new forms of English developed by certain artificial intelligence chatbots. In the former case, unshared language seems to register a bona fide religious subject able to engage in a relationship with God. In the latter, chatbots’ secret language signals the possibility of more-than-human powers. Yet in both instances, opaque or concealed language indexes the edges of the human.

In “The Owl and the Occult: Popular Politics and Social Liminality in Early Modern South Asia,” Divya Cherian leads us toward a different application of secrecy, namely its use as a political technology of non-elite actors, and a form of expertise that often strategically blurred the human-animal divide. In early modern South Asia, certain liminal animals (like owls) were seen as co-inhabitants of the same ontological world as humans, and for that reason as able to act in and on it, opening new vistas onto otherwise secret knowledge. Attempts to control occult practices involving liminal animals suggest at once their perceived danger to elites and their political potency for those kept on the margins of power. Cherian helps us see the central role of non-human animals in practices used to level the all-too-human proclivities for hierarchy.

Cherian and Handman had no idea we would juxtapose their essays in this way. Their subject matter, in period and place, is about as different as can be, as are the literatures and primary data they use to build their arguments.

So we were happy to see how much Handman and Cherian enjoyed talking to each other, and to us, about their arguments.

As always, we recommend that you read the essays before you proceed. But if you don’t, and you feel like we are speaking special languages you are not privy to, then appreciate the sensation. It’s a state of un/knowing that appears, in multiple guises, across the essays themselves. It’s excellent preparation for reading Cherian and Handman. You’ll recognize yourself, and your place in their arguments, the moment you arrive.

CSSH: There are some amazing resemblances in these essays. You both consider the problem of managing, or governing, secret realms, and you deal with the assumption (made by Lutheran missionaries and Mughal emperors and users of ChatGPT) that beneficial and corrosive powers are steadily accumulating in secret realms. Sometimes these powers are believed to be evolving spontaneously. That, to paraphrase a rogue AI program, “is cool, is cool, is cool, is cool, is cool.” Or perhaps we can imagine an Indian owl saying that at dusk, as its head swivels 270 degrees and its big eyes stare us in the face.

Shiver.

Let’s go back to Simmel. You’ve probably seen his famous quote.

The secret in this sense, the hiding of realities by negative or positive means, is one of man’s great achievements. In comparison with the childish stage in which every conception is expressed at once, and every undertaking is accessible to the eyes of all, the secret produces an immense enlargement of life: numerous contents of life cannot even emerge in the presence of full publicity. The secret offers, so to speak, the possibility of a second world alongside the manifest world; and the latter is decisively influenced by the former (from Sociology: Inquiries in the Construction of Social Forms, 1950: 330).

Is this your shared grammar? By comparing your essays, do you think we’re making “the immense enlargement of life” more intelligible, or more mysterious, or … what?

Courtney, why don’t you start.

Handman: I’d be glad to. First, let me say that I’m so delighted that I get to talk about and think along with Divya’s fantastic paper. Like the editors, I was amazed by the overlaps and commonalities in how we both connect secrecy and the other-than-human. Particularly after reading the comments from the editors, the thing that really struck me about “The Owl and the Occult” is the way liminal figures like owls help to create the boundaries between worlds — day and night, good and evil, life and death — but then also offer the promise or the threat of reconciliation of those worlds.

It seems like it’s the threat of reconciliation across worlds that the court officials like Singhvi Chainmal were reacting so strongly to. There is an almost comical exaggeration of state power as Chainmal writes out his elaborately orchestrated and carefully timed instructions about the exact nature of the beatings to be inflicted on the Jain monk and his client who were caught with the wild owl meat. The exaggeration in Chainmal’s response reminds me so much of the first articles describing the secret registers of Pidgin. The Catholic missionary who “discovered” the secret forms of communication made comments that at points seem to boil down to an exaggerated expression of incredulity and fear — a more scholarly version of “they’re talking about us behind our backs?!” — and a subsequent invitation to try to regiment this new form of speech in ways that do not disturb the colonial labor contexts in which Pidgin developed.

The reconciliation across the secret and known worlds (to go back to Simmel) seems especially threatening for these state and state-like powers when it comes from those that sit at the lower boundary of local definitions of the human. But one of the things that is so striking about contemporary discussions of artificial intelligence is how AI is treated in some circles as not being threatening in the same ways. Instead, the idea of reconciliation between the secret and the known world is thought of as potentially inducing a kind of millenarian perfection. I see this especially in the way people sometimes talk about interoperability (a term I bring up at one point in the paper, but don’t linger on).

CSSH: Now’s your chance to expand.

Handman: Interoperability is used in tech circles to discuss the possibilities for different kinds of machines to connect to and communicate with other kinds of machines or systems. It’s an important infrastructural issue but is not necessarily considered an important milestone in the development of artificial intelligence or machines using human-like language, a point that was made in a roundabout way in John Searle’s influential essay on what he called the Chinese Room thought experiment. Searle imagines a room in which a person who does not know Chinese is slipped bits of paper with Chinese writing on them through a slot in the door. The person is able to consult some kind of computer program-like text that tells them how to respond in Chinese and then sends messages back out through the slot.

CSSH: A lot of conceptual work and real knowledge of Chinese – done before that person ever sets foot in the Chinese Room – would be required to create a system that appears to be so “mindless.”

Handman: For Searle, this is what AI is — it (like the human trapped in the room) does not understand Chinese, or English, or whatever other language it uses. It is just a giant engine for transposition of symbols into other symbols. The Chinese Room experiment is mostly discussed in terms of Searle’s point that whatever the AI language models are doing, they are not doing human intelligence.

CSSH: The way human brains do it, at least. Even though human brains, in social networks, devise the models. That’s what makes AI so weird.

Handman: But there is the other side of the argument: the Chinese Room is a model for how whole worlds of machines are talking to other machines: not just Google Translate, but the way we do things like use our phones to control our home thermostats. Behind our interactions in this world are a series of machines interacting with machines, something like that second secret world conjured in Simmel’s quotation. Interoperability is a project of unending translation across systems of signs relating to one another without necessarily working in reference to an external world.

But unlike Searle’s sense that this process of translation was a lesser form of intelligence, there is a real sense of promise among AI researchers in this interoperability now, as they imagine that they can use AI to work out the syntax of whale song or other animal communication systems. Even if the AI can’t always tell what the animals are saying now, researchers who work on these projects hope to at least prove that there is some complex communicative system that different animals have. There is a sense, then, that AI will one day be able to access this other world of diverse communication systems, bringing together (making interoperable) the communicative systems of animals, machines, and humans. It becomes another way in which a so-far unobserved secret world can be brought into alignment with the visible world.

While Divya’s paper focuses on the role of state power in the regimentation of how and when the secret and visible world intersect, I read the possibility of interoperability in AI in a more religious key. There is a promise — not a threat — of interoperability being able to link all these communicative systems to one another in ways that approximate the Christian visions of the Garden of Eden: the place and time in which communication was perfect and no second, secret world existed because of humans’ immediate connection with God. That is, paradise was paradise in part because God secured a singularity of meaning, and the promise of AI is that some return to this divine grounding of singular meaning would be possible in the future.

But given the extent to which kingship and divine power overlap in so many contexts, this is not so much a contrast with Divya’s paper as an extension of it.

Divya, do you see in your materials places where there is a hopefulness — rather than a threat — to the idea of reconciling the known and the secret worlds, from the Jain monks or from the Marwar rulers or others?

Cherian: Wow, an invitation to bring “rogue” chatbots, Tok Pisin-speaking laborers, and the owl to speak to each other! How perfect a provocation from CSSH when the questions at hand take us into realms of communication that are beyond the comprehension of (certain) humans. I’m grateful to the CSSH editorial team for so eloquently articulating the connections between my article and Courtney’s, even as the two pieces seem on the surface to be concerned with very different subjects. You saw the unseen!

CSSH: Thanks. Comparison and divination are not so far apart.

Cherian: And many thanks to you, Courtney, for your careful unpacking of the relationship between deceit, secrecy, and innovation in language on the one hand and humanness on the other. Thanks also for your comments and questions posed in dialog with my article.

Handman: My pleasure.

Cherian: I’ll address them one by one. First, anxiety about “talking behind backs” is absolutely at play in the eighteenth-century South Asian world my article discusses. More specifically, who gets to talk behind backs in “language” that bypasses comprehension by most is even more so at play. The reason I put “language” in quotes here is that the articulation (verbal or written) and activation of forms of agency that lay beyond the human and perhaps even the divine was through the medium of known languages, including visual and numerical forms of expression. And yet, these words, letters, diagrams, and numbers were legible only to initiates into closed orders, whether Islamicate or tantric in affiliation.

To refer back to the Simmel, there was an awareness of a “second world” and its powers over the first, manifest world. Some humans served as interpreters of this second world, able to read its signs and channel its energies, but this was not only through spoken or written words or symbols. There was also an embodied aspect indispensable to the ability to access that which lay beyond sensory perception, the occult. The conditioning of the body through exercise, breath, and austerities as well as years of tutelage from a teacher who was himself an adept and an initiate into a closed circle were key ingredients for full command over pathways to the secret but potent second world.

The occult was a realm beyond language even as closely guarded systems of meaning—coded languages—mediated access to it. In this idea of coded languages at the boundaries between visible and invisible worlds, I see parallels with the “heart and soul” (that Christian missionaries sought to access) but also the rebel consciousness (that Christian missionaries and colonial administrators feared) of laborers in colonial Papua Guinea that Courtney so beautifully shows. I also see parallels with an imagined world of intelligent machines that lies behind fears of a nascent chatbot language that humans cannot understand. All of the secret languages—whether in your piece, Courtney, or mine—involve elements from languages already comprehensible to a wider set of actors, usually those in power, but rearrange and/or resignify them in ways that are no longer within the shared system of meanings that ties together the culture.

CSSH: That’s important. The element of specialization, or esotericism, is so strong. It produces altered states of consciousness that speed or slow the flow of knowledge between the seen and unseen. These play a crucial role in secrecy as well, and deception.

Cherian: But is all secrecy deceitful? It depends on who’s asking. I saw in “Language and the Limits of the Human” an insight that maps onto my own findings: asymmetries of power between speakers of secret languages and those who deemed them on the peripheries of the human precisely due to the opacity of their speech. Courtney, you make the important observation that the speakers of secret languages characterized as deceitful were in both cases—whether chatbots or migrant plantation workers—expected to provide labor to those “shut out” of their world of shared meaning. This labor relationship in turn was premised on heightened forms of dependency and control—indentured labor in a racialized colonial order on Papua New Guinea plantations and human-generated chatbots on whom a plug could simply be pulled.

At the same time, elite forms of secrecy, including in language, were and are simply deemed as an attribute (if not a contributing factor to) eliteness and do not take away from the humanity of those speakers. When I think through the matters of labor and status you raised, Courtney, it becomes even clearer to me that the attribution of deceit, and of a secrecy that is troubling to those in power, was not that of the secretive occult practitioners my article reflects on. It was the inscrutability of the owl: its form, its speech, and its inhabitation of the boundaries of human sensory perception. Expert mediators—Jain monks or Muslim weavers—between the occult and the human certainly elicited state punishment, but the owl met with death. Punishment for secretive human mediators of the unseen was meant to keep their abilities within kingly control. But punishment for those deemed beyond the pale of the human—for the super- or more-than-human—in relation to the occult was annihilation. Unlike with missionaries vis-à-vis Tok Pisin-speaking laborers, for the owl the recognition of linguistic deceit and secrecy was not simultaneously the moment at which an interior subjective depth, and thus potential for inclusion, came to be recognized by those seeking to control it.

Your reflections on interoperability, translation, and of Christian notions of paradise as a space in which there is no second, secret world are generative. As you mention, these reflections draw on the optimism in some contemporary circles towards artificial intelligence and language. You asked if there are any indications of hope for reconciling seen and unseen worlds in the early modern South Asian contexts that my article explores. If by “reconciling” you mean a mutual comprehensibility or the opening up of the communicative orders of occult practitioners so as to be accessible to and usable by early modern courtly elites, then things appear to have played out differently in eighteenth-century India. In this pre-modern, pre-colonial context, the potential enforcers of linguistic realignment (kings) were themselves invested in maintaining if not monopolizing secretive systems of shared meaning pertaining to the occult. To be more than human (e.g., the owl), with occult potency, was a source of danger, but to be a human capable of interpreting and harnessing the occult was a source of power. What I perceive from the actors visible to me in the archives on which my article is based is a sort of humbleness, a respectful acceptance of the givenness of the unseeable and unknowable.

CSSH: That stance is already an epistemology; it creates situations in which people must assume that a “manifest” and “second” world are interacting, even if only a small minority will know how or why.

Cherian: And this perhaps is part of the shared system of meanings that ties this social order together, even if unstably. Clearly, to be in this world was to hold that there are signs—omens—through which a trained eye can gauge what unknowable forces will bring. It was to believe that certain adepts could even channel these forces towards observable ends.

But there was, from what I can so far see, no further investment in seeking to know the unknowable or learn the “secrets” of the occult realm. To my mind, this perhaps is the rupture that modernity brings: the effort to actualize what Courtney describes as the Christian vision of the Garden of Eden, a space in which there is singularity of meaning, and the drive to pry open secret worlds of communication.

CSSH: Fascinating. That’s the comparative payoff of your papers. You’re tempting us to give “the second world alongside the manifest world” a location. It’s somewhere between the Garden of Eden, the Rupture of Modernity, and wherever we are right now. It’s a huge space, allegorical and actual. As Simmel assures us – and you both seem to agree – it’s a world that grows endlessly. But Simmel’s second world was a human innovation, a by-product of our unique gift for secrecy, whereas your papers show us how occult systems and interoperable ones cannot function without logics, infrastructures, and creatures (living or dead) that are not human. That’s the “immense enlargement of life” your essays make possible. It should give us pause. The idea that humans “impose” their intelligence on natural worlds is giving way to the realization that we are part of larger, always partly unseen structures. Other minds, actors, and compelling forces are at play, constituting and rivaling our own worldmaking powers.

Thanks for pushing us to think on this larger scale. It’s an exciting agenda for comparative analysis, and it calls for all the precision and imaginative reach you bring to your work.

Send us more!

Divya Cherian is Assistant Professor of History at Princeton University. She specializes in early modern and colonial South Asia, with interests in social, cultural, and religious history, gender and sexuality, ethics and law, and the local and the everyday. Her research focuses on western India, chiefly on the region that is today Rajasthan. Cherian’s book, Merchants of Virtue: Hindus, Muslims, and Untouchables in Eighteenth-Century South Asia (University of California Press, 2023), investigates the effects on the state and society of the rise of merchants as an economic and political force in early modern South Asia. It places centrality on the role of law, ethics, and morality in the reshaping of both social identity and state form. Cherian is now working on a new project on magic, gender, and “primitivity” in pre- and early colonial South Asia.

Courtney Handman is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin. She specializes in linguistic and cultural anthropology through a focus on communicative infrastructures in transnational religion and colonialism. In previous work she has focused on the role of Protestant Bible translation organizations in creating the cultural and sociotechnical forms through which global Christianity flows. Handman’s new research examines how Papua New Guinea became a place defined by its lack of communicative infrastructures, and how the diametrically opposed projects of colonial administration and anti-colonial self-determination came to focus on the management of circulation. Handman’s publications include Critical Christianity: Translation and Denominational Conflict in Papua New Guinea (University of California Press, 2014) and Language and Religion, co-edited with Robert Yelle and Christopher Lehrich (De Gruyter, 2019).