Aeron O’Connor concludes her CSSH essay, “Opera as Critical “Synthesis”: Theorizing the Interface between Cosmopolitanism and Orientalism” (65-3, 2023), by writing, “Opera and anthropology may appear worlds apart, but they share a history of fascination with the Other, of sometimes Othering others, and of trying to make distant Others legible to audiences and readers (Boon 1999: 9–13). Both have emerged from privileged social circles but have since become appropriated and transformed across diverse social and geographical spheres by some of the subjects they traditionally treated as the Other.” Intrigued by these connections, we asked O’Connor to say more.

Throughout much of my time in Tajikistan, the people I worked with frequently challenged the post-colonial critiques I had learned as an anthropology student, not because post-colonial thinking was unpopular, but because it provides only a partial view of what life has been like in Soviet and former-Soviet Central Asia.

Many regional scholars have addressed this, asking, for instance, what the relationship is between the “post-colonial” and “post-Soviet,” and exposing nuances that muddle the former, sprawling category and the confines of the latter (Moore 2001). Yet, situations and questions I encounter in my research continuously turn my attentions toward ethnographic and historical materials that fit uneasily within the concepts I adopted as a student in Western Europe.

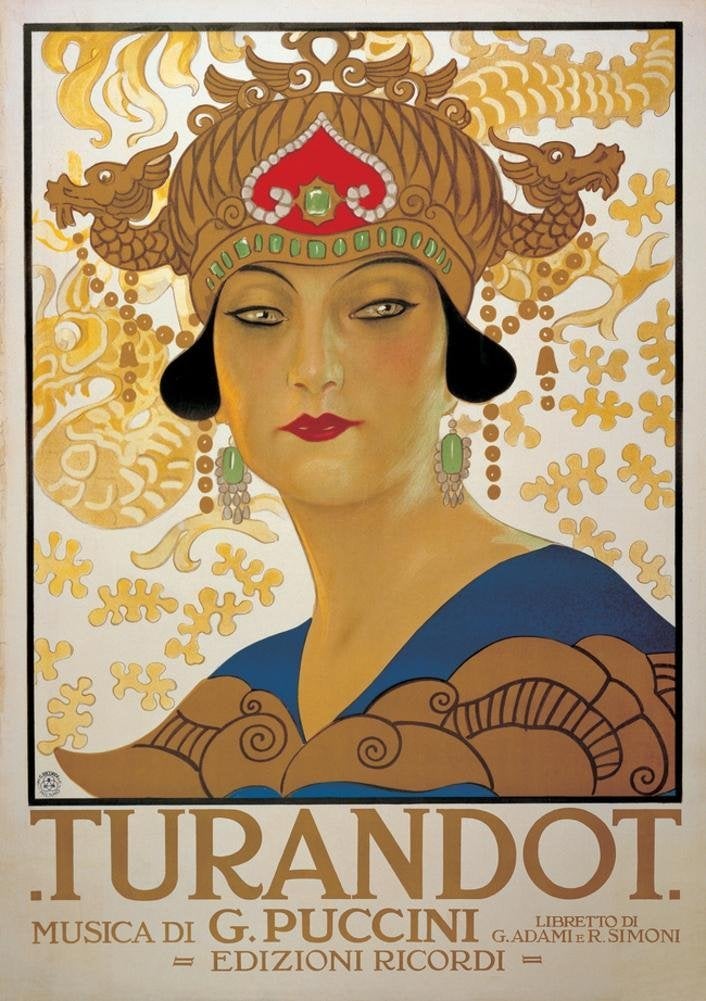

An example is the place of opera in cultural production in Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus, a topic I never expected to explore and was initially reluctant to pursue, given opera’s historical position as an elite European artform that has frequently portrayed exotic Others on stage. My reluctance was compounded by the fact that opera (alongside European classical music and ballet) was only introduced into Central Asia with the formation of the Soviet Union, which trained musicians, composers, and artists across its newly formed Soviet Socialist Republics to develop and express cultural modernity under socialism, especially in the most “peripheral” and “backward” ones.

Later, I realized that my discomfort at focusing on opera mirrored some of the unease and ambivalence I have felt as an anthropologist around producing knowledge about Others. As anthropologists continue to address the complex and often unequal power relations between themselves and their interlocutors, issues of representation and positionality in knowledge production frequently come to the fore. The discipline has addressed these and other issues by, among other things, paying more attention to who we focus our research on and how we portray them, working to diversify the discipline’s professional makeup, treating interlocutors as co-producers of knowledge, and crediting their contributions. The people studied were once treated mostly as peripheral to knowledge production–due to their peripheral location relative to knowledge centers of the global north, and because they were treated as sources of ethnographic data who were marginal to the production of theory. This classic center-peripheries relationship intersects with the knowledge-power dichotomy that Said, inspired by Foucault, famously brought to the center of post-colonial scholarship.

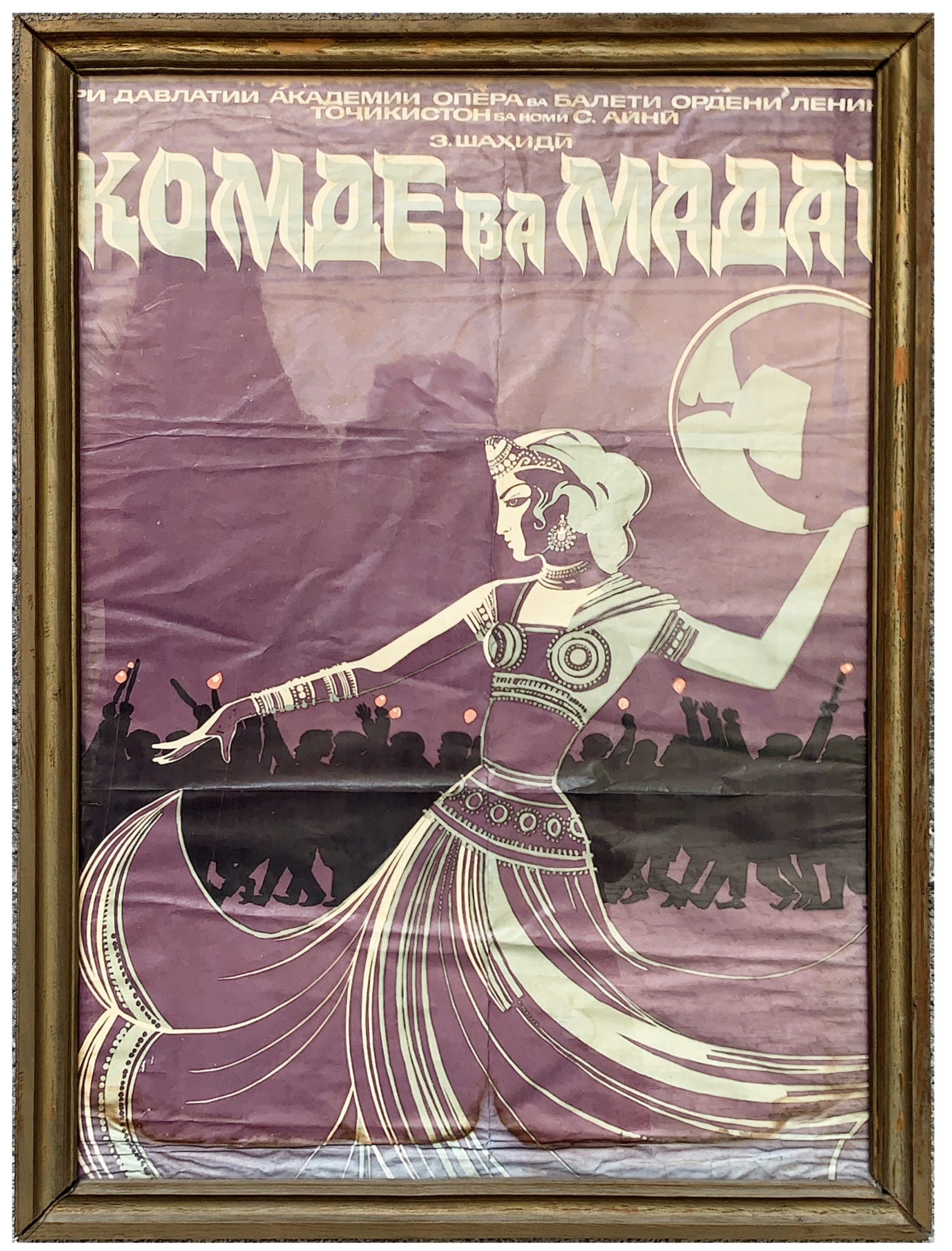

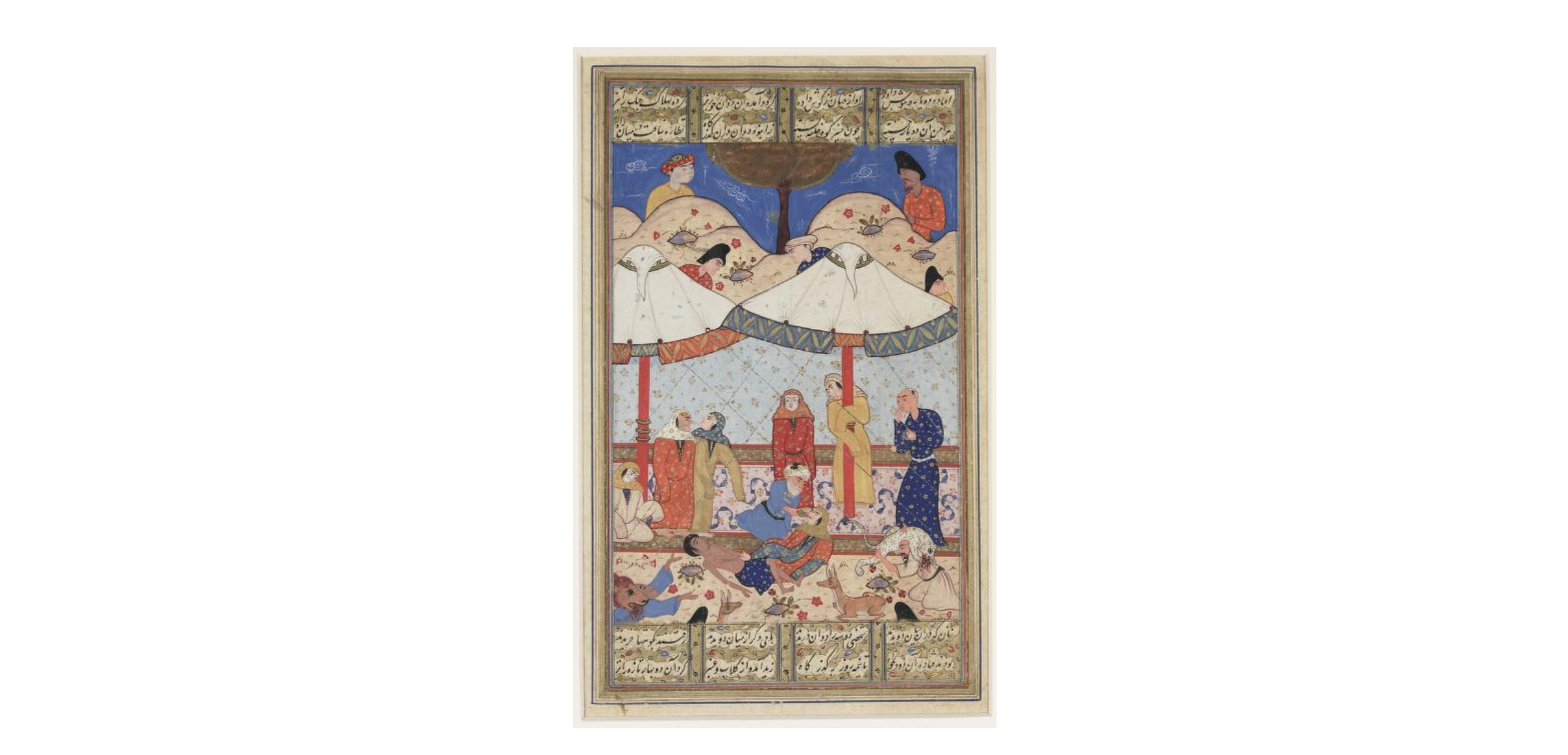

So how can Soviet Central Asian opera speak to anthropological issues of knowledge production? My CSSH article argued that there exist parallels between opera and anthropology, which shed light on the complex power relations involved in producing knowledge about Others. Opera, as it was introduced and developed in Soviet Central Asia, drew inspiration from pre-Soviet Azerbaijani operas as well as Russian ones. It diversified who was portrayed on stage and how, and, most significantly, brought Central Asian composers, musicians, and artists into the fold of opera production. See here for a short clip of the Azerbaijani opera Leyli və Məcnun and here for an audio excerpt from the Tajik opera Komde va Madan.

I learned in my fieldwork in Dushanbe that opera is not perceived there as something that was simply forced upon people in a cultural, colonialist move. In the article, I trace a complex negotiation between local, “peripheral” figures and Soviet ideological and cultural centers like Moscow and Kyiv. This process scrambled who and where is peripheral and is central. I explore this through the concepts of orientalism and cosmopolitanism, which, I argue, in both anthropology and opera are key to understanding the complexities of the production of knowledge about Others.

Locating cultural authority and authorial positionality

To understand opera’s place in the lives of Central Asia’s urban intelligentsia we must ask how and to whom we should ascribe cultural authority in its production, and how to discern positionality. Within these questions we inevitably encounter the anthropologist’s own cultural authority and positionality, since the underlying issue is how and to whom anthropologistsshould ascribe cultural authority in opera production, and how anthropologists can discern the positionality of their interlocutors and subjects. In this, the intersubjective relationship between anthropologist and opera is inescapable.

While anthropology is obviously engaged in knowledge production, the same is not assumed of opera. I approach opera as a form of knowledge production within the USSR, since Soviet-produced operas had to reflect a shared socialist identity as well as recognizable national ones specific to each Soviet Socialist Republic. This was part of a greater process of constructing national identities across the Soviet Union based on cultural and linguistic differences. Opera was thus part of the larger cultural project of producing and disseminating knowledge about people’s cultural differences and ideological similarities across the USSR.

Who had authority to produce this cultural knowledge was not only a point of debate at that time but still is today as scholars evaluate the agency of local composers. Very little research has been conducted on Central Asian opera, which is perhaps indicative of the widespread assumption that local composers had little real agency and perception that their work was therefore merely derivative of Russian opera. There are many ways to approach authority in knowledge production in colonial contexts. In the Soviet case, there was immense pressure from central ideology and policies on individual Republics to produce cultural outputs suited to their agendas. Local artists were rewarded materially, professionally, and in status for producing works that fit the relevant cultural agendas. Yet, it is well documented that even those who followed state policy could quickly fall from favor and suffer punishment, and even persecution, when cultural and political rhetoric changed dramatically, as happened repeatedly throughout the first half of the Soviet period. Not only did this produce a heightened sense of insecurity, but it left murky edges around what was and was not condoned. As I examined in my CSSH piece, some composers and artists took advantage of this murkiness to pursue their own cultural, artistic, and socio-political agendas.

The works produced were therefore products of both centralized influence on local artists and local interpretation, negotiation, and even resistance to centralized rule. Moreover, as I showed, many aspects of these cultural productions drew on local histories and ideas unrelated to Soviet-born and propagated ones. One debate that emerges from a context like Soviet Tajikistan is over who decided what Tajik identity was and how it should be expressed in artistic productions, who had the cultural authority to decide this, and who today has the authority to evaluate the agendas and positionalities of those authorities.

I have used “centralized” here rather than “colonial” because many of the composers and artists involved in opera’s production would have refused such a term. With hindsight, some might today point out that these local intellectuals were complicit in socialism’s cultural colonial project, but many artists still alive, or their descendants, would staunchly contest that portrayal. While some deny any colonial agenda whatsoever to the Soviet project, those who do recognize the Soviet project as colonial are quick to point out that many established members of the Soviet intelligentsia were neither wholly complicit in nor wholly opposed to Soviet colonialism, a point evocatively made by Marianne Kamp (2001).

This raises the question of how much agency we ascribe local intellectuals in colonized contexts. Scholarship on (post)-colonial contexts has long acknowledged ways in which ordinary people related to the colonial state in ambiguous, complex ways. This complexity has been less generously granted those locals who worked in or with the state, whether by choice or not. Within the Soviet context, unlike in most West European colonies, nearly all citizens were granted access to full education, healthcare, infrastructure, and a shared (Russian) language. Local scholars, politicians, and artists were included in the fabric of the state and held prestigious positions in their own Republics and sometimes even in central institutions and government. Thus the distinction between colonizer and colonized is sometimes hard to draw, though many have convincingly showed that it ultimately prevails, nonetheless (Kassymbekova and Marat 2022). Despite these subtleties in positionality, the tendency in much post-Soviet scholarship has been to pay less attention to cultural figures’ views, ambitions, and actions that diverged from Soviet allegiances or interests. As one woman in Dushanbe once put it to me: “Why do people simply call us ‘Soviets’? We don’t call you ‘capitalists’!” I took this as a critique of how the positionality of Soviet cultural figures is viewed first and foremost as “Soviet,” overriding other dimensions of people’s lives and minds.

To return to anthropology, at the heart of the discipline is proactive self-awareness, which has made complex the process of decolonization. Again, changing who we write about and how, and diversifying those who make up our discipline, has sometimes exposed further inequalities, incommensurabilities, and questions of accountability that anthropologists continue to work through. Claiming that we should further diversify who we write about and how by turning the anthropological lens onto “established,” “privileged” Others, like the local intellectuals who produced Soviet opera, I believe we reaffirm the importance of introspection within anthropology. Both opera and anthropology are socially embedded forms of knowledge production, each driven by funding, politics, professional opportunities, and audiences, as well as personal values and constraints. This is how opera has acted as both the object of my anthropological enquiry and the subject of my anthropological self-reflection.

References

Kamp, Marianne R. 2001. Three Lives of Saodat: Communist, Uzbek, Survivor. Oral History Review 28, 2: 21–58.

Kassymbekova, Botakoz and Erica Marat. 2022. Time to Question Russia’s Imperial Innocence. PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo 771 (blog), April. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/time-to-question-russias-imperial-innocence/.

Moore, David Chioni. 2001. Is the Post- in Postcolonial the Post in Post-Soviet? Towards Global Postcolonial Critique. PMLA 116, 1: 111–28.