“Take this down carefully,” a man told the Los Angeles Times over the phone on the morning of September 13, 1972. “I just bombed an Arab’s house in Hollywood. No Arab is going to be safe in this country. Never Again. Never Again. Never Again.” (1) That day, the Jewish Defense League ( JDL) detonated a pipe bomb outside the South Los Angeles apartment of Mohammed Shaath while his wife and two infant children were home. Two months earlier, Shaath, a Palestinian immigrant, had been punched in the face by two members of the JDL after speaking on a local television show. The bombing of Shaath’s apartment was just one of a series of attacks the JDL would carry out throughout the 1970s. On June 2, 1972, they had bombed the Lebanese consulate on Hollywood Boulevard. Before it exploded, a man discovered the time bomb and ran through the building yelling for people to evacuate. Eight minutes later it went off. Amid the debris, the stunned Lebanese consul general, Wadih Dib, asked simply, “Who would do this?” (2) Two years later, in the wee hours of the morning on Sunday, November 11, 1974, an explosion destroyed the offices of the United Nations Association in Los Angeles. Again, an anonymous call was made to the Los Angeles Times: “The United Nations office . . . was hit and it is a thank-you message from the PLO. The message is for letting them address the U.N. Never again.” (3) Yasser Arafat would give his historic address to the General Assembly in New York two days later.

In June of 1978, a theatre on Sunset Boulevard was bombed on the eve of the premiere of a documentary film called The Palestinian. It was narrated by the British actress Vanessa Redgrave and produced by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Redgrave told reporters after the bombing, “The film was made for serious-minded audiences who judge for themselves the truth about the Palestinian struggle under the leadership of the PLO.”(4) The film had garnered much protest earlier in the year when Redgrave was nominated for and won an Academy Award for her role in the film Julia. The JDL and others had called to no avail for a boycott of the awards because of Redgrave’s involvement in the Palestinian documentary. “I salute you and I pay tribute to you,” Redgrave proclaimed in her acceptance speech at the Oscars, “and I think you should be very proud that in the last few weeks you’ve stood firm and you have refused to be intimidated by the threats of a small bunch of Zionist hoodlums whose behavior is an insult to the stature of Jews all over the world and to their great and heroic record of struggle against fascism and oppression.” Outside the awards ceremony, the JDL burned effigies of Redgrave.

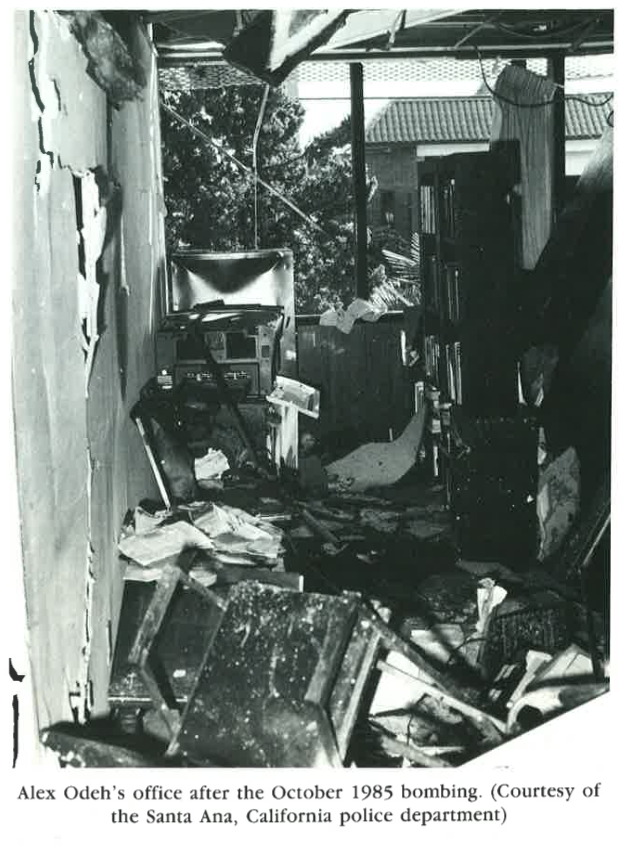

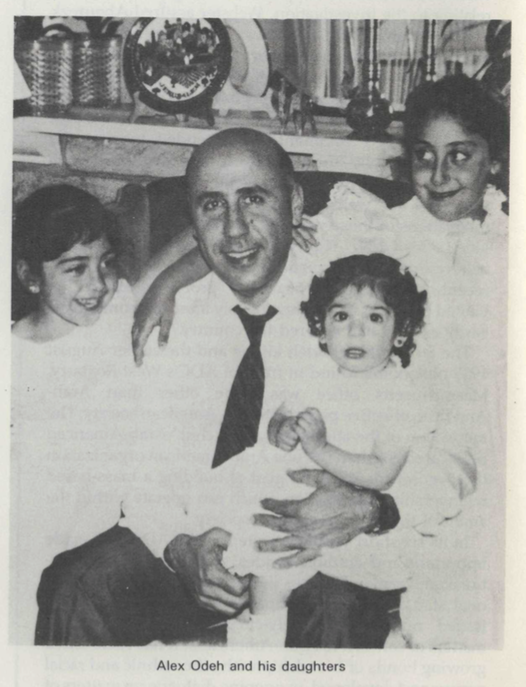

Seven years later, an unassuming office building at 1905 East 17th Street in Santa Ana was the site where the JDL’s bombing campaign in Los Angeles turned deadly. On Friday, October 11, 1985, at around nine in the morning, a 30-pound pipe bomb ripped through the West Coast offices of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), thirty miles south of downtown LA. The bomb was triggered when Alex Odeh, the forty-one-year-old West Coast director of the ADC, opened the doors of the office. His legs were immediately blown off, and when a nurse who witnessed the blast ran up to the hallway to help, she found him covered in debris. Odeh died two hours later during surgery. Seven others were injured in the blast. One witness described the scene: “I thought it might be a sonic boom or earthquake All the cars stopped in the street and people poured out of the building and began running down the street, just like one of those monster movies.” (5) At Odeh’s funeral a few days later at the Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Orange County, described by the activist and lawyer Abdeen Jabara as “a political funeral,” more than 1,500 mourners showed up. Many police officers were there, too, as the event was the subject of an anonymous bomb threat. (6) Odeh’s coffin was wrapped in two flags, one Palestinian and the other American. In addition to the priest who officiated, two prominent LA Muslim leaders read from the Bible. In his remarks to the assembled, Clovis Maksoud, the Arab League’s representative to the United Nations in New York, compared Odeh with Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. The musician Ali Jihad Racy performed. And before the coffin was lowered into the ground, Odeh’s sister Ellen sprinkled soil from Palestine over his coffin. (7) Odeh’s wife, Norma, was presented with a Palestinian flag. After the service, mourners chanted “long live Palestine” and “we will remember the martyr” as they walked back to their parked cars.

The JDL was founded in 1968 by the American rabbi Meir Kahane, who promulgated a virulent form of Arab hatred and loudly advocated violence. In the 1970s, the JDL wreaked havoc across the United States. Bombs were their weapon of choice. In New York, Boston, San Francisco, and else- where, the JDL struck its victims. Sometimes their targets were Nazis in hiding or Soviet diplomats, but often they were Arab Americans and their institutions. In 1985, after Kahane moved to Israel and a few months before Odeh was assassinated, Irv Rubin became the leader of the league, and Los Angeles became the group’s headquarters.

In his 1990 book City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Mike Davis described the LAPD’s “‘West Bank’ strategy of collective punishment in its battle with the ‘terrorists’ (gang members).” Drawing an explicit comparison between policing in Los Angeles and Palestine, he argued that city politicians have treated gang organizers “with the same contempt with which Israel treats the PLO in the West Bank.” (8) In an interview conducted in the wake of the LA uprisings a few years later, Davis raised another comparison:

If you want to give this a kind of cheap slogan, or even a title, the greatest fear of the police, and a real possibility is that gang violence could be politicized to some extent into some ongoing black urban Intifada. I mean an American urban Intifada. There were some Palestinians down at City Hall the other night, and one of them turned to some of his American friends and said: “This is the beginning of your Intifada.” (9)

Davis’s comparisons speak to the connected histories of global counterinsurgency and international solidarity that tie California and Palestine together, a history of rebellion and concomitant attempts to squash it.

Palestinian history is inextricably global, its locations many, and its social, cultural, and political entanglements with the world endless. The writing of Palestinian history, therefore, must necessarily attune itself to the local lives and particular struggles of refugees scattered across jurisdictions and far beyond Israel’s territorial control. The reaction to Los Angeles’s intifada in the 1980s that I relate here, the murder of Alex Odeh and the persecution of the Los Angeles Eight, is one of these histories. Before what is known as the first intifada broke out in occupied Palestine, the JDL and the US government were regularly stifling supporters of Palestinian freedom in North America. The spectacular, private violence of groups like the JDL is not against the state, as it is sometimes represented, but rather constitutive of it. Indeed, as Davis himself has argued, since California’s early days of extermination and primitive accumulation, vigilantes were ancillaries to the Golden State’s white supremacist project.

Odeh was born in the Palestinian village of Jifna in 1944. After his schooling in the adjacent town of Birzeit and then Ramallah and Nablus, Odeh received a bachelor’s degree from Cairo University and later moved to Amman. He went to California in 1972 with the help of his sister who was already living in Orange County. In 1978, he completed a MA at California State University, Fullerton. In addition to teaching at local colleges, Odeh was also an active participant in local Arab American organizations and contributor to the local press. Los Angeles has long been a major center of Arab American cultural life and political activity, as the historian Sarah Gualtieri has recently chronicled. (10) In the 1970s and 80s, the city was host to bilingual newspapers like Joseph Haiek’s The News Circle and Mustafa Siam’s Palestinian Voice, vital sources of Arab American social and intellectual history. Odeh himself was a founding member of the Arab American Press Guild and an editor of The News Circle’s Arabic edition. In 1983, he was appointed West Coast director of the ADC.

The week before his assassination, the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro was hijacked off the Egyptian coast by members of a group known as the Palestine Liberation Front. An elderly man in a wheelchair, Leon Klinghoffer, was killed and thrown overboard during the attack, leading to widespread coverage and condemnation. On the night before he was killed, Odeh was interviewed by Los Angeles’s local ABC affiliate. “We are witnessing that violence breeds violence,” he told the newscaster. He condemned the killing of Klinghoffer and sought to make clear the extent to which the events on the Achille Lauro departed from the aims and activities of most Palestinians. “I think the media mistakenly linked this incident with the PLO,” he said. (11) Media criticism was a task that fell on many an Arab American intellectual. “It is considered natural,” the Palestinian literary critic Edward Said wrote in The Nation a year after Odeh was killed, “that when Leon Klinghoffer is senselessly and brutally murdered, The New York Times devotes 1,043 column inches to his death, but when Alex Odeh, no less an American, is just as senselessly and brutally murdered at the very same time in California, he gets only 14 column inches.” (12) Said notes this is characteristic of a general disregard by Americans for the lives of Arabs and Muslims. James Abourezk, the former senator from South Dakota and then head of the ADC, put it this way on the day after Odeh’s murder: “There is this sense of a kind of lynch mob, from President Reagan on down, it’s cowboy time, on the part of the president, on the part of the media, on the part of Congress.” (13)

Arab Americans inundated the FBI with requests for information about the investigation into Odeh’s assassination. To this day, his killers, now living unmolested in Israel, have never been brought to justice. In 1986, Abourezk and the ADC succeeded in having a congressional inquiry into the violence against Arab Americans, Odeh’s murder being but the most publicized of a series of attacks. In his remarks to the committee, Abourezk said,

When Ronald Reagan demagogues for 3 weeks about the murder of Leon Klinghoffer and is absolutely silent about the murder of Alex Odeh, and when he says, Mr. Chairman, that we have to root out terrorism wherever it is, and when he doesn’t care whether there is terrorism directed against an Arab-American in this country, that is a signal to people that it’s alright to go ahead and do this kind of physical violence It’s the same kind of depersonalization that we saw against Jews by Nazi Germany, that we saw against black Americans over the centuries in this country that allowed racists, whether South or North, to lynch blacks, to commit all kinds of violence against them, without anybody really raising an outcry. (14)

At the time of Odeh’s death, Dar Halaqat al-Akhbar lil Taba’a wal Nashir, or the News Circle Press, was in the process of typesetting his second book.

In 1983, the News Circle Press published Odeh’s first collection of writing in Arabic, Hamasat fil Ghurba, or Whispers in Exile. It contained nearly sixty pages of Odeh’s short poems and fourteen of his essays, an intellectual contribution rarely acknowledged in accounts of his murder. One essay in the collection reflects on the Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, who was himself assassinated along with his niece Lamis in 1972 in Beirut. In another essay, a parody of a travel brochure to the United States, Odeh criticizes those wealthy Arabs who come to the United States to see Miami and New York and other tourist destinations. These Arabs ignore what he calls al-Yeman al-Ahkdar—the Green Yemen—that stretches from Bakersfield to Modesto. (15) Known as California’s Central Valley, the land between those two cities is one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions and has long relied on a continuous supply of laborers hailing from across the globe. In the 1970s, Yemenis became the latest group—after Punjabis, Armenians, Chinese, and Mexicans—of migrants working the factories in the fields, as Carey McWilliams called them. Odeh draws the attention of these hypothetical Arab tourists to the first martyr of the United Farm Workers movement, the twenty-four -year-old Yemeni organizer Nagi Daifullah, who was clubbed to death by the police in 1973.

In 1994, Odeh’s family and friends succeeded in getting a memorial for him erected in front of the local public library. Designed by Algerian American artist Khalil Bendib, the nine-foot-tall statue of Odeh has him donning a toga, clutching a book in one arm, and a holding a dove in the other. The memorial has been a constant target of vandals. In 1997, after lines were drawn across the statue’s neck and wrists with red paint, Irv Rubin, the chairman of the JDL, told the press that he is “disgusted by the statue and isn’t concerned with the vandalism.” (16) “I think the guy is a war criminal,” he explained, without irony. As Walter Benjamin wrote in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.” (17) In 2002, awaiting trial in Los Angeles’s Metropolitan Detention Center for plotting to bomb a Southern California mosque and the office of Lebanese American congressman Darrell Issa, Irv Rubin cut his own throat and died.

Less than two years after Odeh’s assassination, Rubin could be found outside the Federal Building in Los Angeles holding aloft a sign that read “Arab PLO Commie Dogs Beware of JDL.” (18) The occasion for his protest was an immigration hearing convened to decide the fate of Michel Shehadeh, Khader Hamide, Julie Mungai, Bashar Amer, Ayman Mustafa Obeid, Amjad Mustafa Obeid, Iyad Barakat, and Naim Sharif, otherwise known as the Los Angeles Eight. While Odeh’s murder reveals the challenges of Palestinian history in the United States, the well-known case of the Eight exemplifies a specific kind of American history: the history of legal violence by the state itself. The US government has long used incarceration, intimidation, and deportation to squash political activity. Recall the expulsions of Emma Goldman in 1919 or C. L. R. James in 1953. The depth and breadth of the surveillance and sabotage undertaken by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, however, constituted a new level of intrusion, suspicion, and violence. Take, for example, the case of the Black Panther Party, founded in Oakland in 1966. Internationalist and anti-imperialist in its politics and practice, the Panthers repeatedly expressed their solidarity with the Palestinian people on a world stage. Consequently, their embrace of the Palestinian movement served as fodder for the US government’s surveillance and infiltration of the Panthers. As Ammiel Alcalay put it, “the counterintelligence program, otherwise known as COINTELPRO, embraced a fundamental axiom of Israeli propaganda: to be against Zionism is to be an anti-Semite.” (19) The FBI’s practice of sending fabricated letters was summoned in this regard. The Bureau sent letters to Meir Kahane, the founder of the JDL, purporting to be a father concerned about his son who has just joined the anti- Israeli Black Panther Party. (20) The letter’s intentions are clearly to incite JDL violence against the Panthers.

While wide swaths of the American public were fingered as subversive by the federal government during the tumult of the 1960s, Arab Americans had to contend with boutique intimidation efforts against them. Operation Boulder, as it was known, was a large-scale campaign of government surveillance on Arabs in the United States initiated by Nixon’s administration in 1972, a year after COINTELPRO was exposed and terminated. The FBI, CIA, INS, IRS, and other federal agencies collaborated to surveil, interrogate, and deport Arab Americans under the guise of anti-terrorism. This despite the fact, as Elaine Hagopian noted in 1975, “the only reported and verified acts of terrorism in the US related to the Arab-Israeli conflict were found to be committed by Jewish Defense League members.” (21) Meanwhile, auxiliaries to the state abounded. While the JDL meted out violence and intimidation openly, other groups worked in secret. In 1993, it was revealed that the Anti-Defamation League had been spying on Arab Americans and other supporters of Palestine for more than two decades, paying police officers and others to illegally gather information and documents. (22)

On January 27, 1987, the Eight were arrested in early morning raids across Los Angeles—from Long Beach to North Ridge—for purportedly supporting the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Years later, one of the Eight described the harrowing morning: “We were arrested at gunpoint, shackled, and held in solitary confinement at Terminal Island, a maximum-security state prison, for twenty-three days.” (23) Arresting officers simply laughed when they were asked about the civil rights of those they were detaining. The arrests were the culmination of an extended effort of surveillance. One FBI agent, “Patton,” lived right next door to Khader Hamide for months in the same apartment building in Glendale. “Don’t I know you?” Hamide asked one officer who came to arrest him, to which Patton admitted, matter-of-factly, “I’ve been living next door to you.” (24) Imprisoned for more than two weeks before being released on bond, the Eight faced constant abuse from their jailers. “They put two of us in a six- by-ten cell for 23 hours a day,” recalled Hamide. “For the first two days, the lights were on 24 hours a day and a camera was pointed at my head. We were allowed no phone calls . . . some of the guards called us many racist names and made sure we could hear the racist jokes they were telling.” (25)

Echoing the FBI, the Los Angeles Times described the PFLP on the day after the Eight’s arrest as “a Marxist terrorist branch of the Palestinian Liberation Organization.” (26) They were charged with advocating “doctrines of world communism” under Section 241 of the McCarthy-era McCarran- Walter Act, otherwise known as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. The law was passed by Congress despite a veto by then President Truman, who objected to its racism. In addition to the act’s anti-communist provisions, McCarran-Walter hardened already existing racial quota policies, according to the historian Mae Ngai. (27) Pat McCarran, the Nevada senator who spearheaded the bill, argued that the law’s passage was necessary in order to preserve “this Nation, the last hope of Western civilization.” (28) When the Los Angeles Eight where charged under the law in 1987, no one had been deported under Section 241 since 1961. And when the Eight were subsequently acquitted of criminal communism, FBI director William Webster admitted, in the simplest terms, that had they “been United States citizens, there would not have been a basis for their arrest.” (29) Shortly after Odeh’s assassination in 1985, Webster announced that Arab Americans had “entered a zone of danger” and that his agency’s own intelligence revealed that Arabs were susceptible to further attacks from supporters of Israel in the United States. (30) What Webster failed to acknowledge, however, was the threat posed by the FBI.

After the anti-communist charges were dropped, two of the Eight were charged under the “terrorist activities” provisions against naturalization included in the new Immigration Act of 1990. Over the course of their appeals, the patently political motivations of the case were made abundantly clear time and again as the details of the FBI’s surveillance and strategy became known. One memo by the Bureau urged the INS to deport Hamide because he was “intelligent, aggressive, dedicated, and shows great leadership ability.” (31) Writing from Marin County Jail in 1971, Angela Davis elaborated on the legal theory that had unjustly incarcerated her. Nixon and Hoover, she reasoned, shared much in common with the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt, who argued that criminality emerged not from any criminal act itself but simply from the character of the criminal. “Anyone who seeks to overthrow oppressive institutions, whether or not he has engaged in an overt act, is a priori a criminal who must be buried away in one of America’s dungeons,” Davis summarized. (32) In effortlessly reassigning the case from the war on communism to one on terror, the arrest and prosecution of the Eight exposed plainly the duel paranoias of the national security state. The editors of the Middle East Report put it this way in 2007 as the case of the accused was coming to an end: “an odoriferous stew of anti-Arab and immigrant bashing racism, FBI machismo, Justice department malevolence and laws aimed at criminalizing political thought.” (33) In the annals of legal scholarship and advocacy, the Los Angeles Eight case is infamous. Stretching for twenty years—the case was not closed until 2007—and steadily ascending through the federal court system—including the Supreme Court in 1998—the legal plight of the Eight revealed the First Amendment’s limits. (34)

Beyond legal precedent, the persecution of the Eight had a devastating effect on Palestinian activism in Southern California, instilling fear in many of the region’s politically involved Arabs. Publicly, the FBI’s prosecution of the Eight rested largely on the fact that some of the accused were involved in distributing the PFLP’s English- and Arabic-language magazines, Democratic Palestine and al-Hadaf, to small liquor and grocery stores. Surveillance photographs of Khader Hamide and Iyad Barakat picking up the magazines—which could be easily found in shops and libraries across the United States—from Los Angeles International Airport were key pieces of evidence in the federal government’s flimsy case. Consequently, many Arabs in the LA area began to hide their Arabic-language publications at their homes and shops. “I’ve already cancelled subscriptions to magazines that might trigger the FBI and immigration service. But should I also throw away the magazines I already have?” one Arab American woman asked. (35) During folk dances and other cultural events, photography was avoided as fears that such images would fall into FBI hands grew. Arabs in LA became concerned that their neighbors and colleagues may not be neighbors and colleagues at all but rather federal agents in disguise. “People are nervous,” one Palestinian shop owner told the Los Angeles Times. “How do they know the next day it won’t be us? Palestinians don’t feel safe.” (36)

While the JDL may have resorted to homemade bombs, and today’s alt-rightists and neo-fascists pick up AR-15s, they are often participating in the same forms of repression against the same kinds of people that the state regularly incarcerates and kills. In the United States, as in Israel, Palestinian movement is restricted, speech is censored, thought and action contained and criminalized. Moreover, the treatment of Palestinians in Los Angeles does not depart from that of black, brown, and yellow peoples there, a history that has been well documented by Laura Pulido and others. (37) Los Angeles’s intifada is not Palestinians’ alone. In Joan Mandell and Laura Hayes’s important 1989 documentary on the Eight, Voices in Exile: Immigrants and the First Amendment, Father Luis Oliveras, a leader in the sanctuary movement in Los Angeles, spoke with abundant clarity when describing the case: “It is directed at ‘undesirable immigrants’ in the United States and what affects the Palestinians will affect the Mexican, Central American, Latin American immigrant. And any precedent that establishes that the government can decide what immigrant is desirable and what immigrant is undesirable or not in our society is dangerous for us in this country.” (38) Certainly, immigrants and their political speech were not the only targets of the late Cold War USA. The popular uprising that gripped LA in 1992 arrived in the wake of a decade of Reaganism: a ruthless campaign of austerity that was accompanied by the ceaseless vilification and policing of the poor and Black.

Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire taught us that the tools and theories of counterinsurgency moved readily between colony and metropole, between Algeria and France, between Vietnam and Watts. Today, such exchanges are even swifter than the imperially connected world confronted in the crucible of decolonization. Buttressed by the likes of Silicon Valley and its imitators, the Los Angeles police and the Israeli military readily trade their propriety technologies of surveillance and pacification. (39) At the same time, however, Black activists in the United States regularly engage their Palestinian counterparts, sharing their own tactics and histories. In narrating the murder and persecution of Palestinians in Los Angeles, I have only begun to account for the history of the Los Angeles intifada and its attendant counter-intifada. A full accounting remains impossible, for the ideas that animated Palestinian activism in LA and the forces that tried to crush it remain. For now, this much is clear: the history of Los Angeles’s Palestine, of Palestinians in California, cannot be extricated from the history of the United States more generally or indeed the history of the Palestine that lies on the Eastern Mediterranean.

Notes

(1) Dorothy Townsend, “5 Suspects Arrested in L.A. Bombing to Avenge Israelis: Jewish Defense League Leader Is Included in Group to Face Charges,” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1972.

(2) Doug Shuit and Richard West, “Bomb Rips Lebanese Consulate in Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1971.

(3) Jack Jones, “Bomb Rips U.N. Center in L.A.; Anti-PLO Motive Suggested,” Los Angeles Times, November 11, 1974.

(4) “Two Suspects in Blast at Theater Arrested,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1978.

(5) Teresa Watanabe, “Bomb Kills Arab-American Leader, Man Who Defended PLO Dies,” Mercury News, October 12, 1985.

(6) “1,500 Mourners at Rites for Man,” Daily News of Los Angeles, October 16, 1985.

(7) Pat McDonnell Twair, “Ellen Odeh Nassab,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, October 31, 1989, 25.

(8) Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (London: Verso, 1990), 34–36.

(9) Cindi Katz and Neil Smith, “L.A. Intifada: Interview with Mike Davis,” Social Text 33 (1992): 33. Not all comparisons between the Palestinian intifada and the uprising in Los Angeles were made in a positive register; see, for example, Arch Puddington, “Is White Racism the Problem?,” Commentary, July 1992.

(10) Sarah M. A. Gualtieri, Arab Routes: Pathways to Syrian California (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

(11) David Reyes and Lanie Jones, “Bomb Victim Pursued Non-Violence, Lived with Threats,” Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1985.

(12) Edward Said, “The Essential Terrorist,” review of Terrorism: How the West Can Win, ed. Benjamin Netanyahu, The Nation, June 14, 1986, 832.

(13) Dave Palermo and Gary Jarlson, “Santa Ana Bombing Kills Arab Committee Director,” Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1985.

(14) US Congress, House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Criminal Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary, Ethnically Motivated Violence against Arab Americans, 99th Cong., 2d Sess., 1986, 34.

(15) Iskandar ‘Odeh [Alex Odeh], Hamasat fil Ghurba (Los Angeles: Dar Halaqat al-Akhbar lil Taba’a wal Nashir, 1983), 153.

(16) Bill Rams, “Statue of Slain Arab-American Defaced,” Orange County Register, February 7, 1997.

(17) Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1969), 255; emphasis in original.

(18) Bruce V. Bigelow, “Jordanians Accused of Affiliation with Marxist Group Released on Bail,” Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1987.

(19) Ammiel Alcalay, “Memory/Imagination/Resistance,” South Atlantic Quarterly 102, no. 4 (Fall 2003): 853.20 Ibid., 853–855.

(21) Elaine Hagopian, “Minority Rights in a Nation-State: The Nixon Administration’s Campaign against Arab-Americans,” Journal of Palestine Studies 5, nos. 1–2 (1975–1976): 101. For more on Operation Boulder and Arab American responses to it, see Michael R. Fischbach, “Government Pressures against Arabs in the United States,” Journal of Palestine Studies 14, no. 3 (1985): 87–100; and the relevant chapters in Salim Yaqub, Imperfect Strangers: Americans, Arabs, and U.S.–Middle East Relations in the 1970s (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016), and Pamela E. Pennock, The Rise of the Arab American Left: Activists, Allies, and Their Fight against Imperialism and Racism, 1960s–1980s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

(22) Abdeen Jabara, “The Anti-Defamation League: Civil Rights and Wrongs,” Covert Action Quarterly 45 (1993): 28–37.

(23) Michel Shehadeh, “Horror at Home: An Innocent Victim’s Story,” in It’s a Free Country: Personal Freedom in America after September 11, ed. Danny Goldberg, Victor Goldberg, and Robert Greenwald (New York: RDV Books, 2002), 311.

(24) Ronald Sable, “FBI Man Lived Next to Arab Case Figure,” Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1987.

(25) Quoted in Nabeel Abraham, “Anti-Arab Racism and Violence in the United States,” in The Development of Arab-American Identity, ed. Ernest McCarus (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 200. See also Ronald Soble, “2 Arab Inmates Accuse U.S. Prison Officials of Harsh Treatment,” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1987.

(26) Ronald L. Soble and Marita Hernandez, “Arab-Americans Voice Outrage at Arrests of 7,” Los Angeles Times, January 28, 1987.

(27) Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 237.

(28) Quoted in Ibid.

(29) Henry Weinstein, “Final Two L.A. 8 Defendants Cleared,” Los Angeles Times, November 1, 2007.

(30) Philip Shenon, “F.B.I. Chief Warns Arabs of Danger,” New York Times, December 11, 1985.

(31) Cited in Brief for the American Civil Liberties Union as Amicus Curiae in Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, et al., 525 U.S. 471 (1999).

(32) Angela Davis, “Political Prisoners, Prisons and Black Liberation,” in If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance, ed. Angela Davis (New York: Third Press, 1971), 23.

(33) “From the Editors,” Middle East Report 245 (Winter 2007).

(34) For an account of the Eight’s legal saga, see David Cole and James X. Dempsey, Terrorism and the Constitution: Sacrificing Civil Liberties in the Name of National Security, rev. ed. (New York: New Press, 2006), 41–56.

(35) Nat Hentoff,“Shades of J. Edgar,” San Diego Union-Tribune, March 9, 1987.

(36) Ronald Soble,“Palestinian Community Unsettled by U.S. Deportation Inquiry,” Los Angeles Times, June 15, 1987. See also David Lamb, “Loyalty Questioned: U.S. Arabs Close Ranks Over Bias,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1987; and Stephen Franklin, “Arab-Americans Feel Sting of U.S. Crackdown on Terrorism,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1987.

(37) Laura Pulido, Black, Brown, Yellow, and Left: Radical Activism in Los Angeles (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006).

(38) Voices in Exile: Immigrants and the First Amendment, directed by Joan Mandell and Laura Hayes (Hohokus, NJ: New Day Films, 1989).

(39) Simone Wilson, “LAPD Scopes out Israeli Drones, ‘Big Data’ Solutions,” Jewish Journal, February 13, 2014, http://jewishjournal.com/news/nation/126816/.