Darla Himeles’s full-length poetry collection, Cleave, opens with “The Self in Transit,” a poem that lays a foundation for the work. We are immediately whisked into a world that bridges dream with reality by way of disclosure: “I turn, pretzeled with pillow, / tray table rattling, // the brass handle/of a hardwood door & open it.” The landing of the plane in “The Self in Transit” is an apt way to begin a collection about challenging life events, circumstances, loves, and losses. The landing itself is more than an arrival: it is an opening to ongoing self-transformation beyond the limits of Himeles’s traumatic history. And the poetic route after the first poem is full of the “smokey scaffolding(s)” and “ghost gardens” like those referenced in the following poem in the collection, “Home.” The yearning for greater relational harmony and equilibrium echoes throughout Cleave. For Himeles, home is a space that illuminates the elusive desire for comfort despite a complex labyrinth of familial strife.

Himeles’s poems are compelling in their specificity and in their movement toward the unexpected. “Instructions from My Father” begins:

Look, hang up and go play Beethoven’s third symphony, second movement, the first several minutes, and report back. I’m sure it will convince you. There’s beauty in this world, see, but also anger.

After a characterization of the emotive, disharmonious qualities of the music, the poem (a sestina) unfolds into a rendering of the dissonance in the verbal exchange between father and daughter. It is a rugged and absurd interaction, one that assaults the psyche: “Then think of violence. Let your mind go there. / Picture being stalked.” The second movement of Beethoven’s third symphony, absurdly, becomes the father’s proof that his daughter needs a gun. The speaker’s father asks: “Will / you listen now? I can help you pay for it.”

In addition to being an often-fraught journey toward desired relational harmony, Cleave is a journey back in time, one which brilliantly reveals the tension between life occurrences that are harsh or violent but that can be softened or healed through a generous intellect, through an act of imagination. In her poem, “In the Beginning,” Himeles writes:

I believe in the beginning, how it is always shuffling backward, how every brittle thing softens in reverse. This fig leaf, stiff as paper, once knew how to be small, potential, a speck of star.

There is a wistful longing here, a harkening back to the unrealized potential of loving-kindness. Yet, in other poems, Himeles deftly presents the opposite picture via snapshots of highly destructive adult behavior and sometimes unbearable cruelty. The collection contains scenes of domestic abuse that present the psychological impact of trauma. The scenes are feral in their depiction of the ravaging of childhood innocence. We see this in “What it Felt Like,” a surreal retelling of a formative childhood scene. Himeles writes about the speaker’s mother’s “pink robe pooled below as she rose to her toes, / then up further, naked, / the knife between her breasts turning.” There is always an aching reach toward nurture and healing through these difficult memories and retellings of former times.

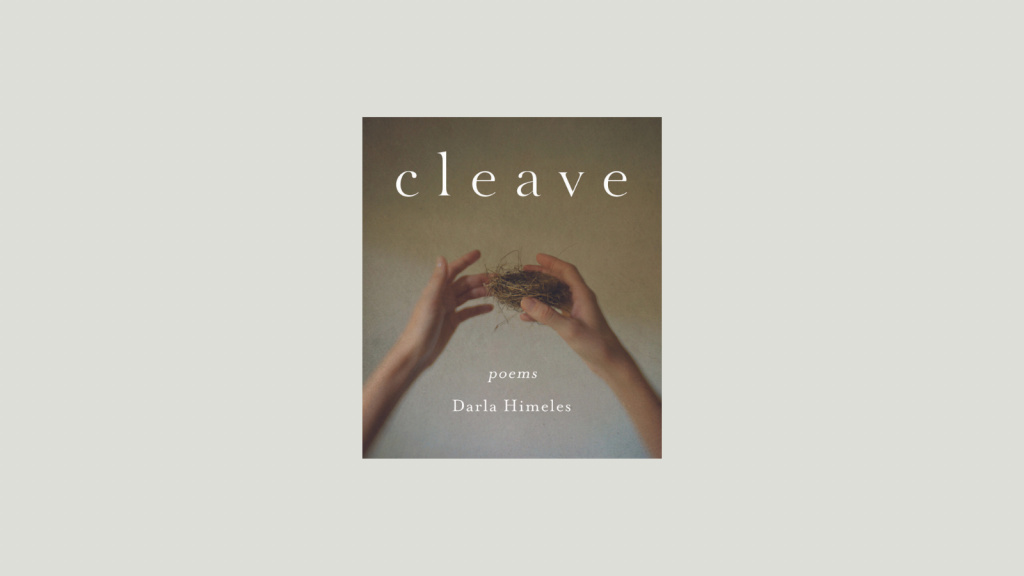

For example, the reach toward nurture and healing is explored in the poem “Claremont, California, 1989.” The poem hints at the complexities of a father’s psyche as he attempts to remove a “twig woven bird’s nest” to show to his children but in the process slips and drops the nest and its contents: “the nest tipped eggs to pavement. / All cracked. This was the first time, / in memory, my dad wept.” The sense of the father’s compassion for the birds’ eggs that met their demise, juxtaposed with the knowledge that he was abusive and spent time in jail, as revealed earlier in this and other poems, adds poignancy to human sorrows that are buried deeply. In this poem, Himeles demonstrates the multidimensionality of complex relationships. She also illustrates how poetically “cleave” can be, both an act of splitting something into dramatic disparity and can also mean the opposite—a clinging to what is good within the heart. This is part of the incredible chiaroscuro effect that Himeles achieves throughout the collection. Sometimes, love can be seen within disjunction even as the untenable is rejected. Cleave is a canvas of contrasts.

The beauty of the “transit” aspect of poems within the collection is that you cannot know what Cleave is initially, not until the collection is savored in its entirety, the pieces of the images subtle as they emerge but dynamic and forthright in their intended afterglow of intense feeling. This adds great enjoyment and depth to the reading experience. An example of this is an excerpt from the curious poem entitled “Pigs That Ran Straightaway into the Water, Triumph Of.” It begins:

When Jesus casts demons into pigs, they leap from steep banks to sea. Some translations suggest lake. The water, salt or fresh, muffles a mania of snouts. The pigs drown.

It is intriguing to think about how a parable about pigs fits in with the self in transit via this poetic journey. Perhaps the secret to how this poem relates to the spirit of the entire work centers on a feeling that it engenders inner trust in the self’s ability to assess what is right. When Himeles next writes, “He is the lord // I will never understand / through human stories,” the door opens to a very wide range of possibilities based on the speaker’s questioning of paternalistic power. When this poem is viewed in relation to the entire collection, we see that the speaker’s mind has embraced a feminist recalibration of power as a means of surviving, and carrying, the scars of trauma.

Above all, Cleave provides a satisfyingly honest connection to struggles dealing with life forces that challenge one’s capacity to thrive—or even to exist at times (see “Poem to My Therapist about the Abyss”). The poems are linked by a marvelous spirit of survival that permeates even the most difficult scenarios and engenders great hope even in the most challenging moments. In this sense, the poems themselves encapsulate a generative force that is full of life and promise. Ultimately, the writing moves into the realm of love and intimacy that is playful and fulfilling and leads to efforts to conceive a child. The speaker never gives up on the idea of home; instead, she expands its definition as she continues to move toward it.

If you want to feel what honesty and connection to self are, go no further than Cleave. It is a gift of life beyond struggle. It is a nest of comfort in the process of persevering through personal trauma despite an agonizing past. The comfort is found in transforming what was into poetry that not only heals but, in its presence, somehow grows flowers in the detritus.

MC Catanese currently serves as a Community Teaching Assistant within the University of Pennsylvania’s continuous on-line program in Modern and Contemporary American Poetry. She was an Extension Director for the Westminster Conservatory of Music in Princeton, New Jersey, before devoting extensive energies to making visual art and studying poetry.