Unsolved Histories: A Postcard, A Package, and the Pieces of a Family Unearthed

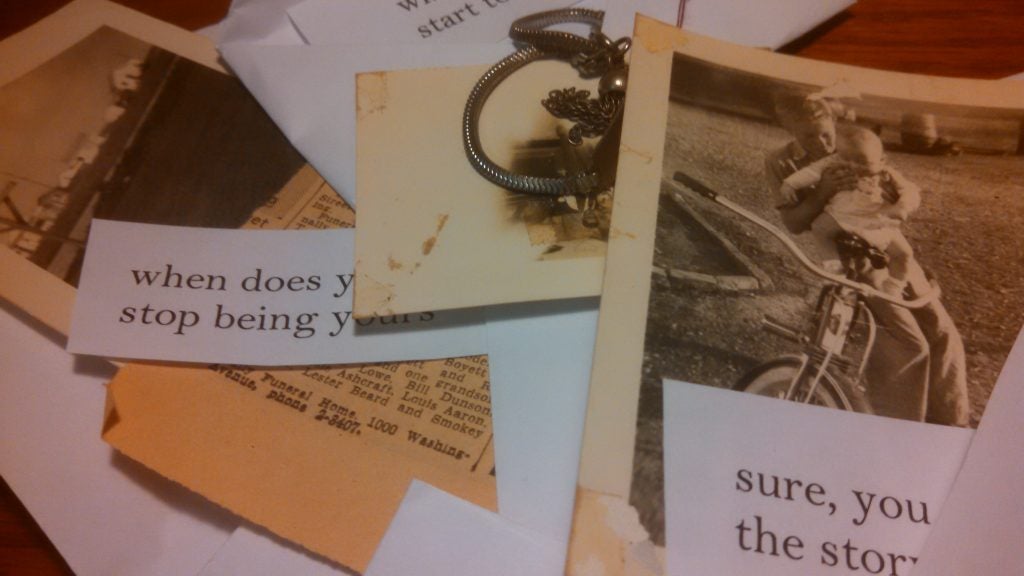

Last July, in an attempt to spare us from the summer heat, my son and I took refuge inside an estate sale. The house was overrun with strangers, everyone ogling the goods left behind by the home’s previous owners. We, too, did our fair share of ogling—peering into rooms and closets in search of treasures left behind. Eventually, I found them: dozens of vintage postcards from around the world, none of them yet sullied by stamps.

Unsolved Histories: A Postcard, A Package, and the Pieces of a Family Unearthed Read More »

Last July, in an attempt to spare us from the summer heat, my son and I took refuge inside an estate sale. The house was overrun with strangers, everyone ogling the goods left behind by the home’s previous owners. We, too, did our fair share of ogling—peering into rooms and closets in search of treasures left behind. Eventually, I found them: dozens of vintage postcards from around the world, none of them yet sullied by stamps.