The greatest gain that ere I knew/ Was made in the blackness of the night

– St. John of the Cross

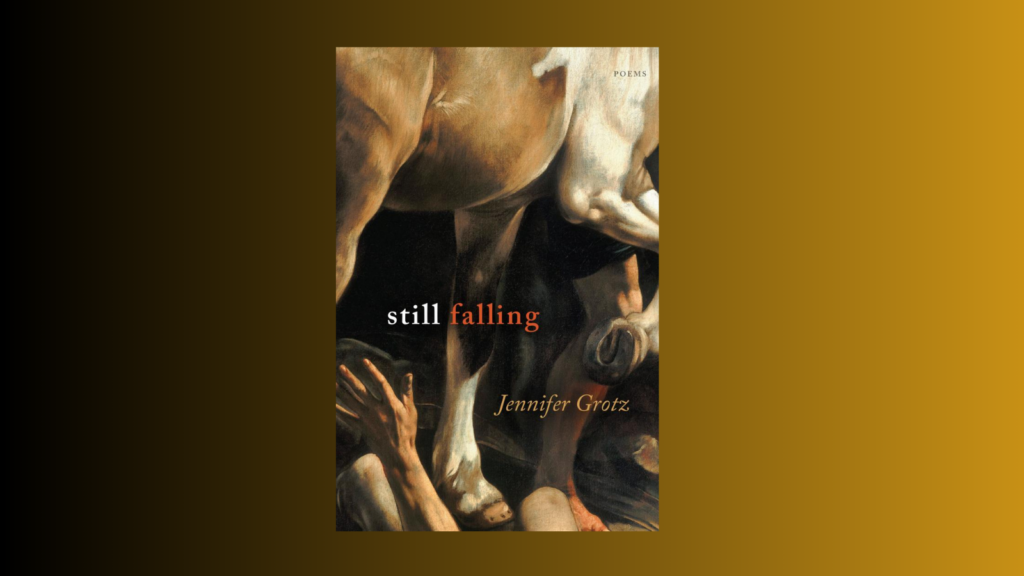

There are at least two renderings of Caravaggio’s Conversion of St. Paul, which was first commissioned in 1599 by a Roman treasurer, Tiberio Cerasi, for his familial chapel in the Santa Maria del Popolo. The first version captures the moment of St. Paul’s conversion in a more traditional scene; a flash of light, the appearance of Christ, Paul being thrown off his horse, the disorientated fall stunning him on the ground. A scene of immense physical pain, hands over eyes in a dark blindness, Paul’s exigent fall communicates, among other likely sentiments, fear.

This rendition, however, was rejected due to a stylistic difference between patron and artist. Caravaggio’s second attempt, still extant in the Cerasi Chapel, depicts Paul’s conversion in a far less standard orientation, in comparisons which can be defined through absence; Christ, now just a stream of light illuminating the scene, is effaced. The horse, docile, is tamely centered. Paul, face up, hands outstretched in penitence and rebirth. Wielding the typical chiaroscuro which makes Caravaggio so recognizable, in the second portrait, the binaries between light and dark collapse and instead harmonize as the vehicle of inoculating surrender and acceptance.

This is the cover image of Jennifer Grotz’s 2023 collection Still Falling, which felicitously explores similar tensions of negation, acceptance, and surrender. Just as Paul is confronted by God, grief, in its many forms, confronts the speaker of these poems; disappearances of love and of life compel an exploration of (or a fall into) a significant aesthetic challenge: the capture of conversion. As in the poem “January,” the speaker warily proceeds:

At first, like grief, the snow

covers everything. Then it begins to reveal

the wan and sickly rainbow of our presence,

cinnamon-sugar of boot-worn paths, dog urine,

roads rimmed with black exhaust. Or

in the woods carpeted with new snow,

ground threatens to give, unstable ice

creaking like floorboards below.

Winter necessitates looking down.

We may wander through acres of grief long enough to experience a melt or to witness a new layer of snow paint over evidence of existence like a landlord, yet we are clearly grounded in a state of such awareness. “Cinnamon-sugar” and “dog urine” linger in the air as they do on the line. The speaker builds a home in such acuity, laying “[floorboard]” and “[carpet],” in the forest of grief, or as they later mention, in their “mind/of winter.” The speaker of this poem, and many others, is conscientious of a necessity for caution, of the cracks in the ice, of a portended fall. It is an agentic and self-referential procession through the process of grief and, in many cases, art itself, that defines much of Grotz’s collection.

Take for example the overt instances of the inhabitations of living language that populate the collection: in “May,” we find “birds…nesting in the hollow of each vowel” of a Chinese restaurant sign; in “Grief,” “countless tiny frogs leap like exclamations;” or in “Rain,” the rain lands in “little claps…it is a sentence, a syntax that continues,/a spell of little letters, a voice.” Language, like a home, is at once quotidian and reverent. Employing images of linguistic transcendence akin to a type of magical realism, Grotz’s speakers remind us again and again that language, and indeed poetry, is a vehicle by which to access the sublime. But what is perhaps more interesting about these moments is that they are self-referential metaphorical acts, defined by an overt “metaness” that brings attention to language and its limits, an active blending and equilibrial establishment of a literal into a figurative. In a Caravaggian-like tenor, such a self-referential mode allows for binaries, specifically of grief, to be traversed and consistently deconstructed. The lines between mysticism and dreamscape (such as the poems, “Medium,” “iPoem,” “The Living Hand,” “Incantation,” and others) and the ordinary and tellurian (such as “Heading There” and “Over and Above” or poems that lend a temporal hand to an organizational arc, “November,” “December,” “March,”…etc) can exist in a distinct and well balanced unison with their complements, but even within these poems there is evidence contrary to such categorization. As in the poem “Free Fall,” the speaker receives the news of a loved one in a coma while observing a sunset:

I marveled

at the loss in store. Though I saw the beauty.

A sky stained every color but green. A slow,

liminal glower stretching flat and thin

as settling smoke, a horizon and a unit of time.

Let us go then, you and I, while she, I

shuddered, was a patient etherized upon a table.

Then I shuddered again as the man

standing next to us jumped

and fell and kept falling. Terror bloomed,

then his parachute. Then the literal and figurative

reordered, then what we’d reached for

instinctively in the moment of falling . . . then

wordlessly we let go of each other’s hand.

These lines reveal the delicate tension and unraveling present during an initial shock, the inceptive moment of grief. The foreshadow of loss brushes across the page like a watercolor, blending not only the portended passing of a loved one, but the loss inherent at the end of each day with the setting (a daily fall) of the sun. Absence tethers itself to cycle.

This is punctuated near the end of the poem by another meta-nod, “Let us go then, you and I, while she, I/shuddered, was a patient etherized upon a table,” which implicates reader as if they were the “new friend,” and transports us alongside the cliffs edge. Toes overhanging the sheer drop, palms sweating in anticipatory fear, we commiserate with Grotz’s speaker both internally and physically, in the lyric distance we travel to the speaker’s loved one “etherized upon a table” and then, physically adjacent and present with the speaker, to the man “free fall[ing]” off the cliff. We then witness a reordering of “the literal and figurative,” a reshuffle of reality and imagined impulse, the parachute opens, and initial thoughts become dispelled.

What is made apparent by this type of paradoxical “reordering” of the literal and figurative, a reoccurrence throughout these poems, is that it provides the continual means by which to refigure language as its own mode of conversion. Such vertiginous movement allows Grotz’s speakers to navigate the disorientation of a fall and delicately deconstructs the nuances of grief and of loss – inherent in loss is the plenty of life. Grotz’s rigorous poetics instructs the obvious, that grief is a messy internalization of awe. When the speaker “reorder[s],” we witness an active, cognitive shift in understanding; a way of understanding what is, is by what is not: “I marveled/at the loss in store.”

But self-referential poetics must toe a delicate line and is subject to its own palpability. To my sense, Grotz navigates this well but there are some poems that begin to creak under the weight of their own “meta-ness.” Poems like “iPoem” or “All the Little Clocks Wind Down” are a seemingly too rigid and resolute examination of poetry rather than the exercise in flexibility required to achieve the pliant examination of language and grief made evident in so many of the poems. It is necessary, especially in a collection so indebted to a self-examination, to examine the medium itself, but some moments can begin to falter under their own ambitions of self-awareness concerning the worth and limits of poetry (a self-awareness, I might add, that may at points tread a line of self-deprecating irony, given the frequency of success of most, if not all, of the other poems in the collection).

While I am generally apathetic to poems being about poetry, or writing for that matter, this is not to say that all poems that approach this challenge are subject to the same overbearingness. As in “Marseille,” we receive the following meditation: “I stare at the sea when a great ship floats on the horizon/from a distance I could never swim alone/until I perceive it’s not fading away, it’s fading/into being, in the time it takes to write this, it’s here.” Transversant and insightful, the speaker looks at the world with an eye patient as one examining art, a painting, itself. It’s an eye which views art itself as a temporal act; one that resists the confinement of page or canvas and instead is imbued with life. As in the faux-eponymous poem of the collection, “The Conversion of Paul,” the speaker dissects the Caravaggio while also curating a dutiful homage to the late poet and professor Paul Otremba; the last lines of the poem contain a similar enactment of temporal reach:

…Paul, thinking of you

when I look at the painting changes it. I see you

vulnerable, surrendered, beautiful and young,

registering that something in you has changed

and what happens next happens to you alone.

And inside you. Conversion is a form of being saved,

like chemo is a form of cure, but it looks to me

like punishment, a singling out, ominous,

and experienced in the dark. When

I used to see the painting, I was an anonymous

bystander. Now I am helpless. It is

and you are, in the original sense, awful.

I can’t get inside the painting

like I suddenly and desperately want to,

to hold him, to help you get back up.

And now, for Paul, everything has changed.

What is clear from these lines is that the mind, as much as a painting, can be restricted to a frame. Grief, a seemingly unrelenting and “helpless” dark, is a distinct internment for both speaker and subject, one, as the speaker puts it, that is “claustrophobic.” Futility is the blinding fulcrum. The speaker observes that “Paul on the ground is still falling,” wherein Paul is notably defined by a perpetual state of being, one that calls attention to the captured permanence of his fall rather than his conversion. It is the construction of this ironic stasis that allows for a devastating discovery, that the living subject of the poem is not granted the privilege of such conversion; if the living can “translate” or “convert” art, why then can’t art have the same translational effect? As despairingly realized by the speaker, if good does exist and “if God himself/is the radiance that struck Saul into Paul,/ then what is the darkness swimming around/everything?”

However, to complement the ekphrasis, Grotz’s speaker communicates with the work of Plumly and Gunn on the painting and postulates “what happens if/a hundred people hold the painting in their minds/at the same time. Will it gain a collective dullness/…But I like to think/it would sharpen the focus.” While one reading of this may give us an ethos of helplessness, self-reference again makes possible a dissolution between binaries of permanence and absence, between a collective and a debilitating singularness. The brilliance of the speaker’s crushing lines is that they make allowances for confinement to become an act of communal participation; the nature of such a collective imbues any act with meaning and life. As the speaker reminds us, “All art traffics in some kind of translation.” While there are rightful limits of art, we may also say that the act of art is a preserved translation of the living, wherein our own translations reanimate such acts. Thus, when we arrive at the moment that “everything changes” for Paul, we arrive at a harmonized grief, one that is dejected by its singularity but assured by collectiveness.

For Grotz, darkness does not fully exist without its complement. The same is true for Caravaggio; for him, darkness is synonymous with divinity. Important for our reading of the Caravaggio is the idea of Negative Theology, which uses darkness as a vehicle of negation to describe God; one who arrives in awe of God also arrives at the ineffable doorstep of all that is unknowable, an event which Saint John of the Cross refers to as the “Dark Night.” In the Conversion of St. Paul (Caravaggio) paints Paul’s event as a moment of acceptance, wherein the binaries of “good and evil” and “light and dark” are rendered as an irresolute particle and instead act as coinciding and telltale signs of conversion. The presence of light and dark are necessary cohabitants, blinding light is a necessary stepping-stone to a supernatural dark, for marvelous unknowing to accrue. As Paul says in his Letters, “this quite positively complete unknowing is knowledge of Him who is above everything that is known.”

To my estimation, what Grotz has been able to achieve in her collection is, if I can call it such, a type of “Negative Grief.” Wielding a modality of self-referential poetics, negated space is allowed to unfurl itself to render grief, meticulously and marvelously, in its many forms, as plainly ineffable. “Still Falling,” as the title suggests, reaches beyond a singularity, and paints a living portrait of conversion, where rivers of joy and wonder are filled from the mouths of desolation and heartache, where “the literal and figurative collude.”

In Simone Weil’s “Gravity and Grace” she asserts, we have the assurance that, come what may, the universe is full. Grotz’s collection, above all else, is a reminder of such assurances, that a fall is not just the unyielding and assertive collapse, but it is also life, the hand resting on the knee before rising. Only in death, as Grotz’s speaker suggests in the closing poem, are “darkness and silence and dust…/only darkness and silence and dust.” Living, however, is defined by its stages of complement, that we do not find just “darkness and silence and dust,” but also light and music and wholeness: If we accept no matter what void, what stroke of fate can prevent us from loving the universe? “Still Falling” is the mindful acceptance of such a void.

Justin Balog is a writer from Beach Park, IL. He is a graduate of the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program and a former Assistant Editor at MQR. His poems appear in Ploughshares, New England Review, The Iowa Review, and Narrative.