“What would any of us do / if freed?”

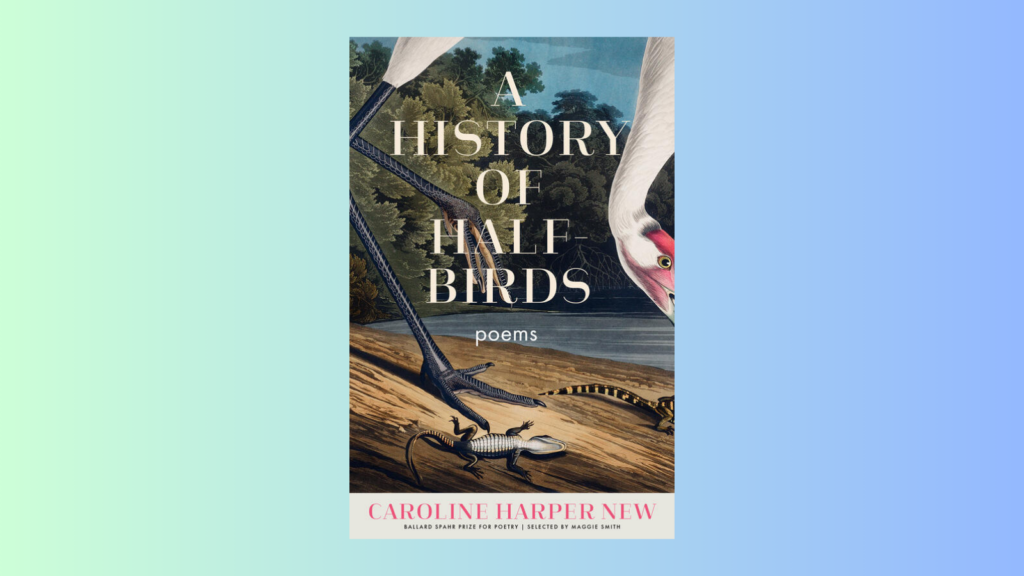

So asks Caroline Harper New in her debut collection A History of Half-Birds, winner of the 2023 Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry. The poems here, both intimate and inquisitive, both personal and public, seethe with life in all its myriad forms: carob seeds “so consistently shaped their weight was used / to measure gold,” a bird dog who won’t hunt, and pigeons who “invented their own religion.” In the midst of this collection’s menagerie of animals and plants both living and extinct, however, A History grips readers most fiercely when the poems investigate the brokenness, the resilience, and the ruggedness of the people within them: an ex-lover and a current one, a mother and those who came before her, the founder of an elephant refuge, and many more.

New, who, besides being a poet, has a background in anthropology, visual arts, and dance, each of which become evident throughout the collection, can be best understood as embodying the spirit of Carol Buckley, the central figure of her collection’s first poem, “The Elephant Mother.” We see Buckley, an elephant refuge founder, with her “Flashlight / prying through the night swamps, nettles seizing at her calves” as she deals with the curious problem of losing her massive circus retiree in the Georgia pines. Like Buckley, New sets off on a fearless search, herself for answers to questions both timeless and urgent: “What counts / as motherhood?” Where does devotion slip into destruction? What do we make of our own ruin?

Similar to Buckley, New carries on this quest for answers despite the dangers lurking within “the overgrown dark” as she shines her light in all manner of crevices, searching for what might be found there; after all, both of them “only wanted / to set something free.” Yet, just as one may be able to experience—or at least imagine—various forms of freedom, so too is New acutely aware of the many forms of entrapment, destruction, and devastation which can render freedom elusive, impossible to grasp. Consider the following moments from her work: the bird bashing its body into a window “over / and over” as the congregation “just kept singing,” the sargassum fish found with “sixteen juveniles in its stomach,” the mother who cannot reach her daughter “without / a thousand holes herself.” New’s collection, then, can be read not so much as a search for freedom from the brokenness of our world, but as a search for freedom despite it.

Of course, freedom’s elusiveness doesn’t staunch the need to pursue it against all odds, just like the natural disasters that wreak havoc on New’s home state of Georgia haven’t, and won’t, stop Mama from ushering her children to the bathtub “[o]n hurricane days” in “The Bathtub,” one of A History’s most haunting poems. It begins:

The poem quickly brings the reader beyond the brief sanctuary of the bathtub to the johnboats outside and “the dove // or more likely the heron” circling above, “her babies / still tucked in the bulrush.” The poem, too, propels the reader through time—later, the speaker is coming home for Christmas with a man from New York; finally, she watches on TV from afar as the swamps of her childhood are devastated, where she reveals a terrible premonition: “I know // it will end with Mama / in her helmet, alone / in the bathtub, holding / her little dog.” Even without her daughters beside her, Mama will continue mothering to the end.

In many ways, the topics swirling together within “The Bathtub” signal the interests of the collection as a whole: motherhood, natural disaster, grief, history. So too is the internal movement of the poem throughout time and space—the way snapshots of adulthood overtake memories of childhood; the way the poem moves far beyond a childhood home before returning to it—an apt indication of the way the collection moves as a whole. While New’s poems expand beyond Georgia to places as far away as Madagascar and the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf Coast remains the collection’s geographical center—both the point of beginning and the place of return.

Further, the way “The Bathtub” weaves across the field of the page is representative of many other poems in the collection, where New’s inventive forms and lively spacing seem indicative of both her background in dance and a visible manifestation of her own voracious quest for understanding, her willingness to keep turning something over and over as she seeks to find new ways into timeless questions. In the midst of numerous forms of movement through the collection, though, New’s recurring “Fieldnotes” poems—“Fieldnotes on Cape San Blas,” “Fieldnotes on Carrying,” and “Fieldnotes on Hydrangeas,” just to name a few—and their prose-poem blocks serve both to stabilize the collection and allow her background in anthropology to rise to the surface.

The fieldnotes poems, most often brief, exude all the raw intensity of notes scrawled on a scrap of paper during fieldwork. Through them, New’s enormous curiosity about the world is cemented; with each one, it becomes increasingly evident that this collection is one borne of a careful, deep observation and attentiveness—one increasingly rare to come by. It’s clear New doesn’t just hope to offer readers a glimpse of the world but to render all of it fully alive on the page, including the “Dead things left by living things” as much as the “living things left by dead.” As such, New urges us to take seriously our job of noticing and interacting with the world in all its splendor and horror. To understand ourselves and this earth, A History posits, we must kneel down and dig in the dirt, comb through the sand, and cup water in our hands and drink.

Moreover, the fieldnotes allow New to shift from a more externally focused, interrogative mode to a more reflective, declarative one. At the beginning of “Fieldnotes on Juniper,” for instance, the speaker declares “I am always looking for proof.” The poem continues to illuminate mind-boggling truths, including “the mountain that once / cupped an ocean in its peak” and the “planets / whose own gravity consumes them,” before ending with a brief litany of plants whose names (“Snakeroot. Slashpine. Love-lies-bleeding.”) are beautiful as they are ominous, revealing the disturbing adjacency and blurriness between tenderness and violence throughout the collection.

Furthermore, this thirst for proof manifests in the importance of fossils throughout the pages of A History. This becomes apparent first with the epigraph from Traci Brimhall (“Dear fossil, I am sorry for the light.”) and continues through the collection’s final poem, where New’s speaker arrives at a central revelation: “All we know // we know from fossils / which are just cavities, occurring in one of two ways : decay or self- / dissolution.” What, then, are we to make of a world when so much of it can be apprehended only by viewing the remains of the destruction that has preceded us, the very remains which we ourselves will—or might, or have already begun to—become? And yet even if decay or self-dissolution is posed as seemingly inevitable, A History never lapses into a hopeless lament. If anything, it only seems to increase the urgency in New’s writing and her fascination for further exploration. Even if, with time, the clock “stakes / its dark dial / in [our backs],” New ushers us onwards with an encouragement both ominous and hopeful, that we might learn “how / to make a house of our ruin.”

We see this suggestion taken literally at the collection’s end as the speaker’s mother moves from the relative safety of the mountains back home to the Gulf Coast amidst a hurricane. Perhaps destruction is coming, or is already here, A History suggests, but who are we not to learn, or at least try to learn, how to live and to love amidst it?

Matt Del Busto is a poet from Indiana. He received his MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program. His work has appeared in The Cincinnati Review, Ninth Letter, and Ecotheo Review and is forthcoming in Copper Nickel and Image. He lives with his family in West Lafayette and works at the Purdue OWL.