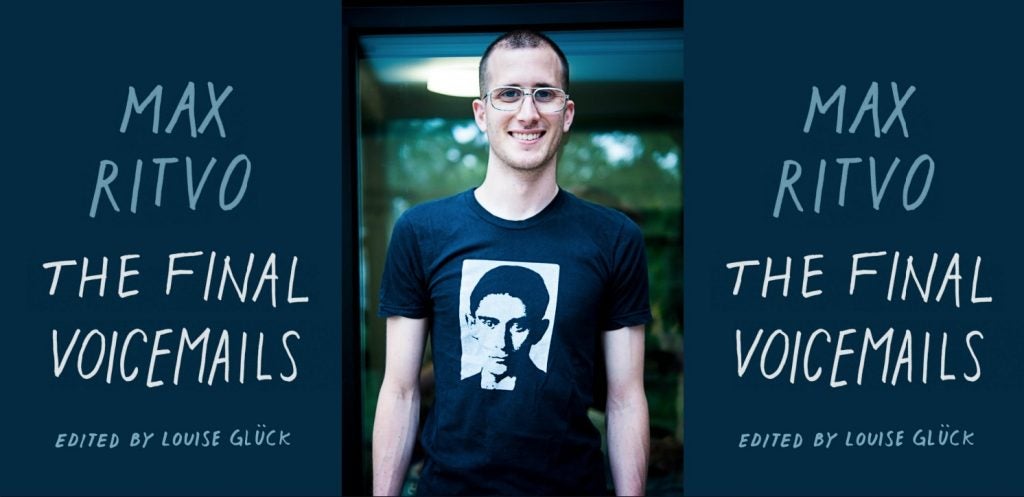

Max Ritvo died August 23, 2016, of Ewing sarcoma, a rare cancer he was diagnosed with at age sixteen. He was twenty-five years old. He was the author of a chapbook, Aeons, chosen by Jean Valentine to receive the Poetry Society of America Chapbook Fellowship in 2014, and his first full-length collection, Four Reincarnations (Milkweed Editions, 2016), was published a month after his death. His second collection, The Final Voicemails, as well as Letters From Max, featuring correspondence between Max Ritvo and Sarah Ruhl, are forthcoming from Milkweed Editions in Fall 2018. Both John Schwartz and Lucie Brock-Broido wrote recounts of Ritvo’s work and life.

In The Final Voicemails, Max Ritvo embraces the difficulty of articulating and sharing meaning from the most vulnerable places of the self. He writes, self-consciously, in a poem late in the book:

If after the poem I am still an object,

then we’ll know that, won’t we?

I hope then, you’ll talk to me,

and promise I make sense of you.

from “Listening, Speaking, and Breathing”

This promise to attempt sense-making offers the reader an intimate nudity that is unpornographic and un-archetypal. In an attempt to express something honestly “meaningful” — something drawn from human perception rather than museum artifact — Ritvo dissolves the distinction between the felt and the experienced. So when Ritvo writes in “Cachexia,” “Today I woke up in my body / and wasn’t that body anymore,” one does not imagine a body adrift. One inhabits the body through Ritvo’s vulnerable details, of body and self, which familiarizes the speaker as an extension of the reader rather than a detached narrator.

Ritvo has an ability to capture a complex galaxy of thought, spindles of planets twisting and eroding, in the simplest universe. In “December 29,” he writes, “If all of me is the part that’s loving / what is left to love?” In a book full of these statements, Ritvo’s poems are less platitude than they are a distillation and articulation of the truths behind vapid clichés and hard-to-describe existentialisms. Every shift in meaning — from familiar sayings into distorted platitudes — rearranges the constellations into new angles, different stories inlaid in the night sky than one would remember. Imagine, looking upward and spying shapes you’d seen, but not like this, not askew in the sparkle of gas, pareidolic, winking out Max Ritvo bent over deciphering a fortune cookie message instead of Orion. Ritvo reinvents the mythic and alters the reader’s expectations to invigorate even the simplest-appearing phrases with meaning.

In coming to terms with his cancer, Ritvo engages the world with an urgency that many of us, if we haven’t felt it before, have tried to imagine, or perhaps were too scared to imagine. When faced with life’s finiteness, what do we take away from it? What do we leave for those we care about? The Final Voicemails is not just the product of a clever mind observing and engaging with the world around it, but an invitation to observe and engage with — and alongside — Ritvo. Undeniably, the collection requests company with which to sit, with which to share. An invitation to not be alone.

In coming to terms with his cancer, Ritvo engages the world with an urgency that many of us, if we haven’t felt it before, have tried to imagine, or perhaps were too scared to imagine. When faced with life’s finiteness, what do we take away from it? What do we leave for those we care about? The Final Voicemails is not just the product of a clever mind observing and engaging with the world around it, but an invitation to observe and engage with — and alongside — Ritvo. Undeniably, the collection requests company with which to sit, with which to share. An invitation to not be alone.

The Final Voicemails is divided into two sections; the first section, “The Final Voicemails,” are the last poems Ritvo wrote. Louise Glück, in the Editor’s Note, remarks on the singularity of a twenty-five year old who left “bodies of work so urgent, so daring, so supple, so desperately alive.” The second section of the book is Ritvo’s undergraduate thesis, Mammals, which includes poems that appeared in some form (sometimes under other names) in Four Reincarnations. Dialoguing between the two sections, Ritvo traces the path between questions and answers, sideways figure-eight, back and forth. These poems require infinite cycles as the two sections reflect on and mimic each other. In this manner, the sections feed off each other’s energy, holding up to multiple readings as successive meanings and intersections appear. In “Bustan,” Ritvo writes:

The globe of tea is like a locked sun,

Or a fish with a tail,

So good at being a tail

It reaches it’s head again,

And makes the head a tail,

Until it is one round tail.

Tea reflects the values, beliefs, and meanings we rely on during distress to sustain our energy. And tail can be read tale: human narratives cycling through what we know we know, what we are learning to know now, and what we just knew a second ago. As Ritvo acknowledges in “Tuesday,” “there’s a past being pointed to / that already understood the present.” The book characterizes a process of understanding one’s personal story that is at once overwhelming and exfoliating.

In this first section, Ritvo vulnerably presents the architecture of his life for examination, from changes in his body to the changes in his relationships. The section ends with “Leisure-Loving Man Suffers Untimely Death,” in which Ritvo writes:

Sure, I wish my imagination well,

Wherever it is. But now

I have sleep to fill. Every night

I dream I have a bucket

And move clear water from a hole

To clear ocean. A robot’s voice barks

This is sleep. This is sleep.

I’d drink the water, but I’m worried the next

Night I’d regret it.

I might need every last drop. Nobody will tell me.

The feat of the poet to narrate their own departure from this conscious earth is rare and poignant. As distorted and masticated as the imagery is, Ritvo is a reliable guide, treading equally the known world, the unknown, and the ethereal.

Yet the collection continues. In fact, Ritvo wrote Mammals first. This section re-begins the story, like Ritvo sitting back down after an intermission of using the toilet and refilling his drink: where were we? Ah yes: “Lajuwa Forgets How to Love.” In resetting the collection, his focus zooms out, panning to look at the horizon and at the landscape all around. He makes the ego small and distant to instead perceive a new perspective, to inhabit non-Max Ritvo, and quite literally: the first poem of this section begins in personification. Direct and obvious, perhaps, but reincarnation, nonetheless.

The “autobiographical” meanders back into Ritvo’s poetry. After “Bustan,” Ritvo writes consistently more and more intimately again, as if he’s reintroducing himself, a younger self, to the reader: hello, I have transformed; please, excuse the residue. After all, this book cannot solely be “about” death or passing; Ritvo is attentive to love as a locus between life and of human joy. Love and death coexist not only in the canonical artistic and poetic tradition (from Keats to Lorca, featuring duende, to Plath to Valentine) but also in Ritvo’s relationships—romantic, platonic, medical, and readerly. These are relationships that shared in Ritvo’s life and that grieved at his passing. Ritvo embraced the importance of love to his poetry, saying in an interview:

We evolved to cooperate, and our brain built all these weird wires into us to get us to do it. Our pleasure is concatenated with other bodies, other human beings, in a way that it is with nothing else. And so, of course I write of love. I write to summon love, so I will get the girl in the end. I write to commemorate love, so that it will last forever. This is the ancient way poetry works.

As the title suggests, The Final Voicemails is a monument to those close to Ritvo. It is a project partially born of love: how to give it, to receive it, and to have as much as possible in our lives — questions that are easy to ask and much harder to answer.

To read The Final Voicemails is an experience of deep love, at the most microscopic level, for Ritvo and for his dedication to sharing his life and experiences with openness and vulnerability. Great poets do not need to convince readers that their world is real and meaningful because they have already taught readers how to live inside their world and to experience it, to sit with it. For all of these reasons, I cherish Max Ritvo and his words, ones that I will revisit many times. This is the ancient way poetry works.

Daniel Neff lives in Ann Arbor, where he is an MFA candidate in poetry and teaches with the InsideOut Art Literacy Project in Detroit. His poetry has been published in Ninth Letter, Zyzzyva, Interrupture, and Whiskey Island, among others, and has won the 2017 Academy of American Poets Prize and The Meader Family Award. Find him on Instagram @elastic_heron.