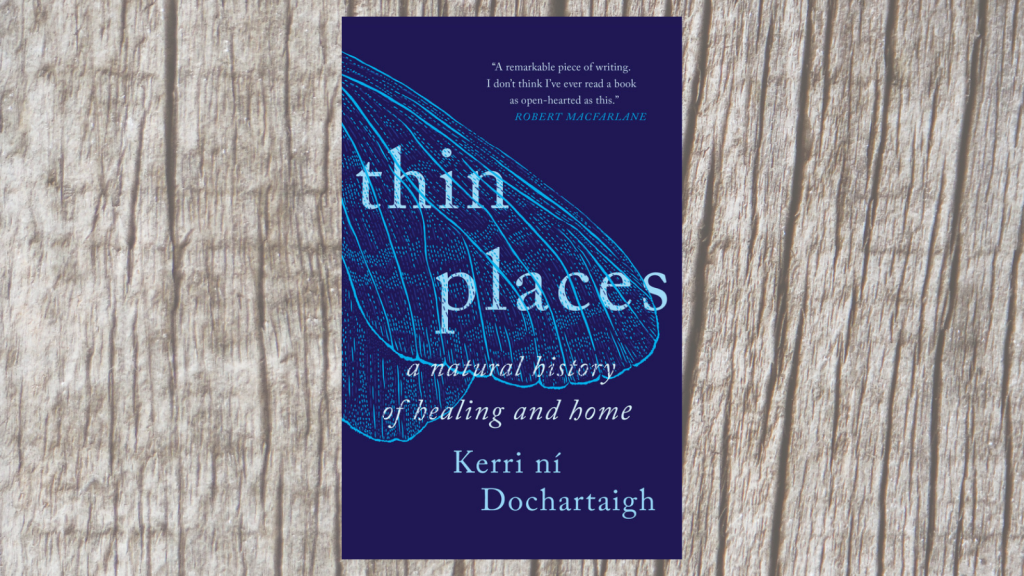

Kerri ní Dochartaigh has written for The Guardian, the Irish Times, the BBC, Winter Papers, and her memoir Thin Places was shortlisted for the 2020 Wainwright Prize for UK Nature Writing. M.D. McIntyre spoke with Kerri ní Dochartaigh about Thin Places, which is released in the US on April 12th with Milkweed Editions. Dochartaigh was born in Derry on the border of the North and the South of Ireland.

M.D. McIntyre: Kerri, it is so nice to meet you and get to chat with you about your book. This is fun for me, I haven’t interviewed someone who is releasing their book in another country. Does it feel like you are doing a book launch all over again or does this feel different?

Kerri ní Dochartaigh: Oddly, it feels like this is the first time because of the pandemic. I had no book launch really, no events. I didn’t see my book for many months. Ireland was properly locked down and it came out in January, so I didn’t see it. Book shops weren’t open. So even though I’m not going to America right now, it does feels more real. I didn’t feel this nervous when it came out in the UK and Ireland!

MDM: Well I loved the uniqueness of your book. This felt like a much more complicated homecoming than what you often read about in memoir. There was a real push and pull to deciding to come back to Derry. Did you realize this was the story you were going to write when you started?

KD: I didn’t know until I started writing the book. The book you read is very different than what it was in the early drafts, and even from what it was when I was thinking of it before I started writing. The book had its first life as a children’s story about a little girl and a bird—I wrote that and illustrated it. It was called “North.” And then I wrote a poem about the River Foyle and it was basically all of the book in a poem. Then it was a series of political essays and it won a prize in Wales. Then it turned into an essay that was on Little Taller Website, a British nature writing website. And then, from that essay the book came. The book had nine serious edits. It has done this shapeshifting and it was kind of river-like in how it came to be. In the earlier drafts it was more hybrid and less chronological. It was a lot more ethereal and fragmentary too. Then my editor and agent both felt that I needed to strip it back to the reality of what had happened and what I had lived through. It was through their support I was brave enough—and I hate that word, brave, when we talk about what we lived through, because it isn’t like we had a choice, you know? But my editor and agent are inspiring women, and they encouraged me to write the draft that is this book.

MDM: How inspiring and encouraging for other writers to see a book go through that journey from a children’s story, to a poem, to a series of essays, and finally to memoir.

KD: Yes, and the book I’m writing now hasn’t had any of that journey. It wasn’t banging around inside me the way Thin Places was. In fact, Thin Places was originally called Mudlarking, which is the title of the political essays. Mudlarking is when you troll through mud to find things. London and Irish street merchants survived this way, by finding things and selling them, and the poem was also called Mudlarking – trying to find the mares of us that are buried deep—the identity and the Irish experience of what we carry, and how there is a strata and palimpsest inside us. That was my central image when I was writing, and a focus on how we can excavate that in a tender way—for everyone.

It was a friend of mine who was really encouraging from the beginning of my journey, Claire Archibald, a writer and musician, and she said it’s not a memoir, it is an excavation of self. And it felt like it was what I was trying to do, but I didn’t actually know it.

MDM: That is so encouraging for other writers, that a book can take a while to take form.

KD: I think a book is a creature and it can shapeshift. I always thought of Thin Places as a creature, even a few years later, I still feel that.

MDM: Are there a lot of changes in the edition being released in the states?

KD: There are no changes from the UK and Irish version to the US. I was really expecting changes, other friends have had their books edited heavily and in this case there weren’t any, which felt nice. They even kept the cover designed by Gil Heely, a really brilliant designer.

MDM: Well I have to ask you about the title, because I personally wasn’t familiar with the term before I read it. The term “thin places” means the veil between the physical and the spiritual, the mortal and the immortal, it wasn’t something I was familiar with. I was fascinated with the concept. Did you know that this term might not be well known for other audiences?

KD: Interestingly a lot of American people I know did know the term, so I didn’t really imagine a lot of people wouldn’t know it, but I find it really thrilling that it might be new to some people. When that happens for me and I hear about a new concept I love it. I’m reading a book called Fifty Sounds by Polly Barton which was put out by a UK press, Fitzcarraldo Editions, and it’s about the Japanese language and different phrases of meaning and how they translate roughly. It is just totally mesmerizing. It blows my mind really—in Japanese there is a word for the dripping sound but it also means a lot of other things. The Irish language has a lot of those types of words and phrases too. But the term ‘thin places’ just means what it means, and there are Irish people and British people who didn’t know the term too, and I really wasn’t expecting that.

MDM: Thin Places really has a certain feeling, a real interiority that feels intimate and also feels like it mirrors the time it was published, because we were in the pandemic. There are moments that feel stark, void of people, or even outside influence. Do you feel that your narration was influenced by the times you were writing in? Do you think that solitary contemplation is an important part of nature writing?

KD: I have thought about it a lot, and a lot of people have mentioned that the book is oddly matched for the time, even though it was written before the pandemic. I wonder if that’s just a part of the unseen magic of existence, that things can happen in this way. The type of isolation and solitariness has defined me since I was young. I have always needed a lot of alone time and immersion in the natural world, and then when the pandemic came along everyone was placed in that situation. I wonder if people might have a greater appreciation of being in that head space, or maybe people are done being in isolation and solitary? It could go either way really.

As to the nature writing, I now have the least time alone than I ever have had in my life. I have a very attached young son who I doesn’t want to be away from his mom for very long, and I’m writing my second book which is a nature book, so I hope that the solitary work of nature writing isn’t required because I am not as solitary as I was before!

As for nature writing, we are in a really good place now because we are acknowledging more and more how unfair the publishing business has been in the past. There were really strong male voices at the forefront and now it seems like we are making room at the table for other people, and writers from places we never really allowed into the literary scene. That incorporates race and gender and identity, and class as well, so we are seeing people writing nature who we didn’t get to see before. We see mothers who just get an hour a day to write and they send off to a contest and they win and black writers and BIPOC writers who are writing and being recognized for their work. In the natural world we are all on the same level but that hasn’t happened in the publishing world. Seeing things change gives me such joy.

Now we have the Nan Shepard Prize, a nature writing prize, and the whole point is to raise up underrepresented writers who were excluded. In the UK you see The Willowherb Review will only publish writers of color. We are seeing writers who were always there and we didn’t make room for, and it challenges the idea that we need to be solitary too. Because historically there was the white male writer who had financial means to leave family and go off on their own, and now we can hear from writers who are working three jobs or supporting a family, and these are the voices we need. We are getting more communal writing, rather than solitary. For me it is very intriguing and very exciting.

MDM: Nature writing seems to have an external focus but as I read your book there is an inevitable interiority to the writing that comes when the author finds themselves in the natural world. When you write about the river and the sea, the foxes and dragonflies, it feels natural for the work to be in contemplation of the larger world, but it creates a distance from our modern experience. Did you have a desire to move away from what surrounds you in the city toward nature?

KD: In writing the book, I sometimes move away from the modern experience. I don’t want to say it was cathartic, because it wasn’t, it was really difficult to write the book. I don’t think it healed anything. I still went through what I went through. I still have to choose every day to move forward from what I lived through and I think it was a step I had to take to show other people that they aren’t alone. People have contacted me to say ‘you wrote so much of my existence and my family is so broken from those experiences.’ They tell me that they felt like they couldn’t talk about it, and so if just one person felt like they could talk about witnessing violence or being suicidal then it felt really worth it.

I felt like I had to get this book out to write anything else. It was almost like a blockage. I suppose for me, there is no separation between me and the natural world, I am part of the natural world and when I talk about the fox I’m talking about me and also the world too. When I talk about the loss of insect life, I’m also talking about grieving the impact that loss will have on our society, and us as a race. Because what we don’t talk about still happens. It still matters.

MDM: It felt very relatable to me to struggle with going back home to deal with the trauma of your youth, your community, the Troubles. You could have to choose to keep your distance from the place you are from and that trauma. Did anyone advise you against going home?

KD: Everyone. I have to be honest about the fact that I knew I couldn’t stay forever in Derry. I had this period of time when I could do it. It felt like this important time to make peace and if I didn’t do it I would have regretted it. So now I feel like my personal work there is done. I kind of put it to rest.

MDM: I loved Chapter Ten, “The Grove of Oaks.” It felt like the magic of your book is looking at both the personal and political, and the physical and metaphysical. When I read that chapter, I was reminded so much of what has happened in the civil rights movement in the last few years, and more recently the war that has started in Europe. Your book feels very poignant for these times, and seems like your work is carrying a message of how social and political change occur despite all odds, or even when hope feels lost.

KD: People have said the world can learn so much from the north of Ireland. I have heard that repeatedly. A Russian leader said the reason they were invading Ukraine was similar to the Troubles. But I do not see the crossover there. War and violence is never a good idea. It is never a good idea to pointlessly and needlessly throw away life. There are similarities and differences in all conflicts, but what we see when we look at the situation in the north of Ireland was a very specific type of peace process, which I look at in the book, that required a humility and respect that we often don’t see in war. All I can hope in this current situation with Russian and Ukraine is that we begin to see glimmers of respect somehow. But it is very worrying. And a lot of the stuff that has played out in America as well, what has been missing has been respect for human life.

MDM: You mention the book Grief is a Thing with Feathers by Max Porter in Thin Places. I’m curious what other stories or narratives you looked to when began this project? Did you have a few books either at the beginning or the end that helped you figure out where you were going, or an author that you were reading to help you through the writing process?

KD: I read a lot of Seamus Heaney and poetry during the writing of Thin Places. Also a lot of contemporary literature, and strong female voices who write about the female experience: Sinéad Gleeson, Doireann Ní Ghríofa, and Amy Liptrot. I also read a lot of Audre Lorde. I revisited Alice Oswald, a British poet. I also reread a lot of the classics like Homer, and children’s stories. I’m very into the way children’s stories work and how it strips back the narrative, mythology too, and I read a lot of works dealing with conflict resolution. I was also reading Paul Gallico’s book The Snow Goose. I really need reading in order to write, so I try to spend half my time reading and half my time writing.

MDM: I have to tell you that before I had a chance to read Thin Places I watched Derry Girls—did you watch it too? Do you feel like it captured some of your experience growing up?

KD: Yes! Of course. We grew up at the same time and in the same place, myself and the woman who wrote it. I guess when my work is compared with Derry Girls I get really excited and proud, because it’s clever and uplifting. The whole point of art is to convey feeling. It is why we make art and to touch the person who watches or reads it. If we think of the way the Greeks had the comedies and the tragedies together it was because they touch different parts of us, and give us the catharsis to deal with the situation we are living in. We need both right?

MDM: What are you reading now?

KD: At the moment I’m reading, Fifty Sounds, which I mentioned above and then I’m also rereading a book called Seven Steeples by Sara Baume. It is coming out with a press in the United States this April, Mariner Books. It is so good. I can’t say enough great things about it.

MDM: Do you have any new projects you are working on?

KD: I am writing my second book which is very exciting and terrifying, and a crazy idea with a brand new baby! It is very surreal. I don’t know how I am doing it, but part of being a mother is we somehow have to find a way. It is also memoir and nature writing, and it picks up where Thin Places ends.

MDM: Wonderful, well I can’t wait to continue reading your story. Thank you so much chatting with me.