1.

Even during his lifetime Wang Xizhi was considered God’s gift to calligraphy. According to historic records, his career took off in Earth Year 352, when Master Wang invited forty-two literary figures of the day, who also happened to be his closest drinking buddies, to gather along a gently flowing stream. Small cups, fashioned from lotus leaves, were filled with rice wine and floated downstream. The friends, who were sitting spread out along the banks, were to compose poems on a set theme. If the floating cup reached someone before he was able to complete his poem, he would be obliged to down the cup of wine.

By the end of the day, the friends had composed thirty-seven poems, and Master Wang, who was completely drunk by then, took up his brush and in a burst of energy transcribed all the poems in his legendary running script, adding a preface for good measure.

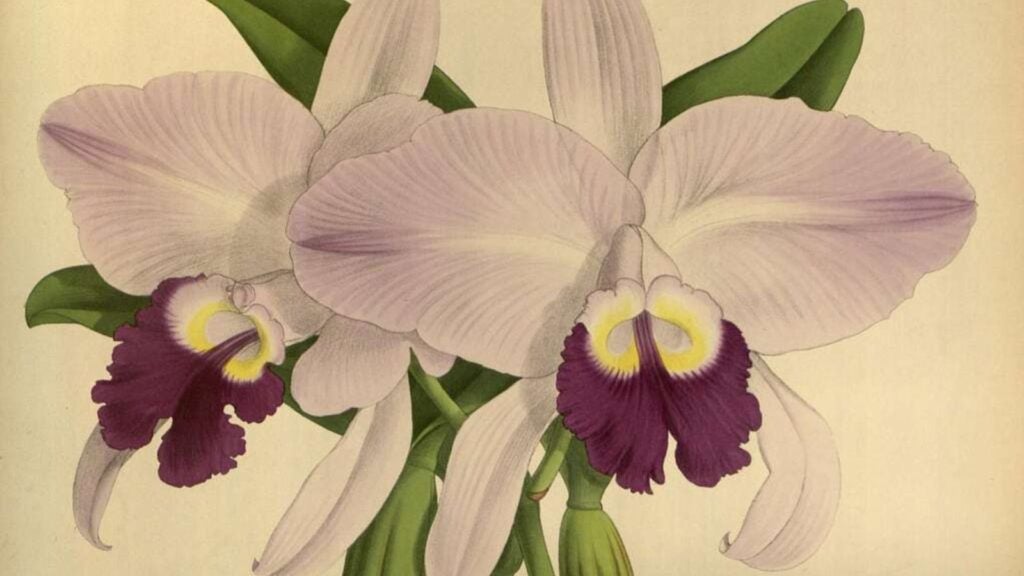

Over the centuries this famous preface became known as The Orchid.

Mi Fu imagined how elevated that gathering of Earthlings must have been.

A dream within a dream.

Then his thoughts darkened as his mind returned to the disastrous events of the morning.

He wanted to ask: why me? But he knew that in the presence of the Emperor of China, asking questions was not an option. Plus, he was in an awkward position, having “borrowed” certain works of art that by all rights belonged in the Imperial Collection.

Another problem was that he had not been expecting an Imperial Visitation. So, he was taken off guard when, approaching his study, he heard a rumbling from within.

His ship was built in the manner of the ancient Five Harmonies Pagoda, with a patina of rusty iron and thirteen separate octagonal decks with eaves that housed the drive system. Some said the barge had seen better days. But he felt it had a classical elegance when docked next to a polished fleet ship.

Located on the top deck, his study looked deceptively small from the outside. Anyone happening upon it would no doubt feel disappointment to find just one small room, would think, Surely this is not where the great Mi Fu stores his legendary art collection . . .

But upon opening the door, that person would discover a delirious vision of gleaming halls. Beyond that stretch, other halls—each more glorious than the last—spilled out one after the other. It was within this space that Mi Fu stored his collection.

A collection that was also the ground zero of his own destruction.

The outer rooms contained countless shelves of unusual rocks and gems, and other natural specimens from across the Diaspora. Next, in the hall of skeletons, reconstituted bones were laid out on shining metal tables. A glass vitrine containing his assortment of fossilized teeth, many carbon black in color, took up an entire corner. It never ceased to amaze Mi Fu that despite the lack of mammals in this part of the Five Galaxy System, there was such a rich abundance of rocks, minerals, shells, and fossils. Most beautiful were the ancient relics of a volcanic and oceanic past that included petrified flora and resins, some containing odd creatures trapped within.

Serving as the Emperor’s Keeper of the Imperial Collection, Mi Fu could declare without a shadow of a doubt that his cabinet was far superior to the one held by the Emperor on Kaifeng Station.

But of course, even if the Emperor forgave him his Cabinet of Curiosities, the Art he had secreted away in the sanctum sanctorum would surely cost him his life. Priceless antiquities and works of art, as well as precious stores of incense and medicines, musical instruments, and books filled massive, black lacquered cabinets, each with their own name beautifully calligraphed on a wooden plaque: “Steeped in Antiquities,” “Fragrance of the Past,” “Abiding in Delight.” While he had never bothered to count the number of items in the Cabinet of Curiosities, the collection was catalogued in his log precisely as follows:

Jade 14,636

Bronzes 14,389

Ceramics 27

Painting and Calligraphy 527,938

Lacquerware 2

In the center of the central room, the viewing room, a long black lacquered table allowed for individual study of the works of art.

As Mi Fu’s only son was quick to point out, viewing really meant copying and stealing.

The fact of the matter was, through years of what Mi Fu called his “art collecting activities,” he was now rattling around space with the greatest art collection in the known universe. The art was all that was left of Earth. And therefore, it was valuable beyond imagination.

This was agreed upon by all in the Diaspora. The art functioned like the gravity that drew the Five Galaxies into orbit around the capital. It carried the dissipating fragrance of a long-lost Golden Age. The perfume of Earth.

Mi Fu knew that this was the reason his only son was so angry.

Tall, with long, wavy hair like his father, Youren was as lanky as Mi Fu was rotund. Again and again Youren had screamed, “What happens if your beloved barge blows up? One accident, one misstep, and all earthlings lose their heritage?”

The boy was right. Mi Fu would somehow have to find a safe home for his collection.

He supposed his son would be happy that the Emperor had finally forced his hand. That morning, stepping inside his private studio, Mi Fu had found priceless antiquities and works of art, as well as precious stores of incense and medicines, musical instruments, and books piled in towering heaps on the floor.

And standing there in the middle of the mess was a man in red robes. A Red-Robed Minister of State.

“Master Mi Fu,” said the Red-Robed one, “How delightful to meet the man considered to be the greatest art connoisseur in Chinese history. And yet, how strange that you insist on walking the streets of Kaifeng Station dressed in the crimson robes favored on earth some five thousand years ago. You’ve said it’s because you prefer the styles back then. But we all know there is more to it. Not to mention that, despite your excellent connections at Court—how can I say this? You’ve never been particularly “career-oriented,” have you?”

Before Mi Fu could respond that the Minister was himself wearing red robes, the toad continued, “It has come to the Imperial Attention that instead of taking care of the Palace Collection of Art and His Imperial Cabinet of Curiosities, of which you are in charge, you have instead been roaming the galaxy on your barge. And here I get to the crux of the matter, that somehow in your travels you’ve managed to acquire an immense collection of important works of calligraphy, paintings, ancient bronzes, and other antiquities dispersed in the Great Diaspora, which by all rights should not be in your possession at all. Does this pretty much sum up the situation?”

“I have no idea what you are referring to, Master-whoever-you-are.”

“But Master Mi Fu,” the Red-Robed one said, “the Emperor Himself is here to weigh in on these proceedings.” He glanced toward a wooden lattice screen, behind which presumably sat the Emperor of China.

And there, as if on cue, was an imperial clearing of the throat.

Mi Fu bowed toward the coughing screen. This could be a problem.

“Master Mi Fu,” squeaked the Emperor, “You are here to stand trial for high crimes against the Empire.”

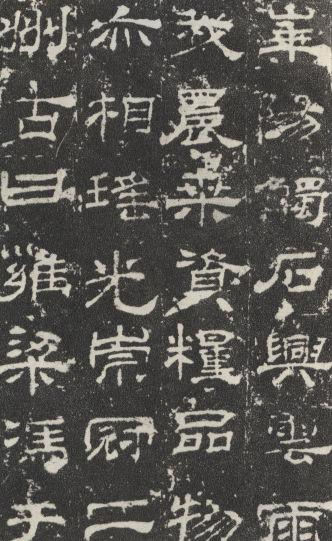

At this, the Emperor dissolved and then reformed in front of the screen, swollen to twice the height of Mi Fu. Dressed in imperial yellow silk from head to toe with a blue-green dragon blazoned on his chest, his eyes were emerald lasers probing Mi Fu. When he spoke, the words noiselessly shot out of his mouth into characters of the ancient calligraphic clerical script, which then exploded in constellations of dying embers.

An impressively realistic holographic projection, thought Mi Fu nervously.

He barely had a chance to read the words before they dissolved:

You are incorrigible and insufferable. You stand accused of acquiring art via a most dubious method, including replacing originals of borrowed works with replicas, and on more than one occasion threatening suicide to friends of my imperial court who wouldn’t agree to sell you their masterpieces, keeping this up until they relented.

When no one spoke, the Emperor—who it must be said, thought Mi Fu, was on a roll—pronounced that Mi Fu was also guilty of stealing plaques from temple gates in the asteroid belts of Kaifeng Station. Indeed, he had stolen these because they provided fine samples of a particular style of calligraphy.

Raising his voice, Red-Robe said, “You must understand that this is a crime against the Emperor and therefore punishable by death.”

The vacuum of silence that followed sucked the air out of Mi Fu’s chest, and he could only pantomime the sentiment “you must have me confused with someone else” through a series of jerks, arm waves, head shakes, and mystified looks.

Chuckling, the Emperor spoke in a final flourish of clerical script:

Mi Fu, if you want to avoid punishment, bring me The Orchid from Jade Mountain.

Mi Fu remained silent, for there was nothing left to say. Closing his eyes tightly, he willed himself to wake from this terrible dream.

But, of course, this was no dream.

2.

How had it come to this? Mi Fu let out an exhausted sigh and wondered what his illustrious ancestors would have made of the glorious new capital of China.

His great-great-great-grandfather was born on Earth and had been a key member of the Evacuation Mission shortly before the end of the Great War. It was a well-known story, especially how they’d evaded the marauding space pirates by hiding in the Oort Cloud for five years. Not so well-known was the fact that more than 75% of the huge freighter ship had been taken up with art instead of fleeing people. But their leader had wisely known it was the Palace Collection that granted legitimacy to their government—not the people. This was why so few human beings had been evacuated from the burning planet. Just five great families, along with several thousand artisans, farmers, and doctors.

At the time, they knew the leadership of other nations (whose names were now long forgotten) had also evacuated Earth. Mi Fu thought they were probably out there somewhere. Maybe in a different part of the universe. Teams of scientists constantly monitored the radio, optical, and UV for any sign of life, but so far it had been only silence. Was it possible that only the Chinese survived this long?

His illustrious ancestor had been a truly wise man. A scholar and a gentleman. Working under enormous pressure, he managed to pick and pack into crates the crème de la crème of the national collection: 7,000 years of Chinese art and civilization in the form of bronzes and jade, ancient ceramics, and thousands of scrolls of painting and calligraphy. The scrolls were easiest to store on ship, but most vulnerable to damage.

In all his wisdom, Mi Fu’s illustrious ancestor had advised the emperor (known as the president of China back in those days) to leave behind the larger bronzes so they could bring more precious scrolls of calligraphy and painting—but the president had been more of a bronze man, famously telling his scandalized great-great-great-grandfather that “real gentlemen prefer bronzes, don’t you know that by now?”

Oh, to be beholden to politicians, presidents, and emperors. How his illustrious ancestor must have torn his hair out in frustration.

One bronze tripod had weighed in at nearly 2,000 pounds. But the president insisted: it had always been kept in his residence, so how was he supposed to survive in space without it?

Having little choice, his illustrious ancestor had complied. But he pressured the president to recognize his contribution to their mission by appointing his descendants in perpetuity as Keepers of the Collection, which was how the position had fallen into Mi Fu’s lap—despite the fact that he was clearly ill-equipped for the job, being more interested in traveling the galaxy searching for his own treasure instead.

But Mi Fu always thought that the position of keeper could be considered more important than emperor. The emperor was assigned in rotation between the Five Families, with a term of twenty years. Each new emperor had to leave his or her planet and galaxy behind, relocating to Kaifeng Station, home of the Art Collection.

Their forbears were like survivors of a great shipwreck: they had washed ashore with a heartbreaking sliver of their greatest books and art—and with only these seeds they had to rebuild a great civilization. Because they had left Earth with so little, the Art Collection had taken on a near-religious authority: whoever controls the Art controls the Five Galaxies.

Lost in the past, Mi Fu hadn’t heard his son creeping up on him. That boy was stealthy as a cat. Where was his cat, anyway? Along with the over 700,000 pieces of art, his venerable great-great-great-grandfather had insisted upon bringing cats on board their evacuation ship. His little Mimi was herself a descendent of feline refugees. He had adopted Mimi after the death of Youren’s mother, but the boy had shown little interest in her.

“Father, I’ve lost all patience with you,” Youren said.

Mi Fu was genuinely shocked that his only son should behave so rudely.

The boy continued, agitated, “What trouble are you in now?”

Before Mi Fu could find words to fill his gaping mouth, the boy pressed on. “Why won’t you stop tempting fate? Can’t you just quietly do your job at court and look forward to an early retirement? Just think how you could spend your days working on your calligraphy, music, and painting?”

“I’ll never retire. Never!” He was sputtering and red with anger. “I am on the cusp of such important work. I have so much left to do.”

“But Father, I assumed you hated court and that you would prefer to be free at last to pursue your multitudinous interests in space.”

Mi Fu realized his son might be making a good point. A very good point, indeed! Hadn’t he always loathed life at court? So many treasures remained to be seen in the Galaxies. Hadn’t he always longed to see the calligraphy of the ring system with their dazzling inks of oceanic mollusks and ground shells? And there were the Nine Bronze Tripods, hoarded by Warlord Chiang in the Betelgeuse sector. Traveling along the cosmic web, he could seek out glorious new and untold treasures until he had seen his fill of the great beauty of the universe.

“But if I retire, that would mean that you . . .”

“Yes, Father, I would become Keeper of the Collection.”

“My dear boy, do you consider yourself ready for such a position?”

“At this point, wise Father, I don’t appear to have a choice, since you continue to be the source of endless trouble, not just for me, and Mimi, but for the Emperor, who it seems is growing tired of your looting.”

“Looting?” Mi Fu was incredulous. When would his son understand what he was trying to accomplish. Did the boy have no vison? Still, he wanted to diffuse his son’s temper, so tried to calmly ask for their current position.

“We are on track to arrive at Jade Mountain in six months, Father.”

Mi Fu hadn’t felt the twisting, floating feeling that always accompanied the Xùnsù drive. Were they on lousy fusion? “Six months? Didn’t I tell you that I have a week to bring back The Orchid or the Emperor will have me put to death?”

“No Father, you didn’t tell me that.”

“Well, my life is under threat, so don’t you think you had better pour some oil on it?”

“The Xùnsù drive, Father?”

“Obviously.”

“Yes, Father.”

In truth, the Mi Fu Family Calligraphy and Painting Barge had seen better days. It was a hybrid ship, but they almost never engaged the Xùnsù drive anymore, instead utilizing the fusion reactor. It was cheap and reliable, but also painfully slow. Hence, the barge moniker.

Youren disappeared and Mimi hopped onto Mi Fu’s lap, purring.

His beloved orange tabby. Why couldn’t his son be more loyal and devoted, like Mimi?

To read the rest, you can purchase the Spring 2023 SomaFlights special issue here.