Vanishing point: the point or points in a work of art at which imaginary sight lines appear to converge, suggesting depth

Q: Who is the speaker?

A: The poet? Me? You? Us?

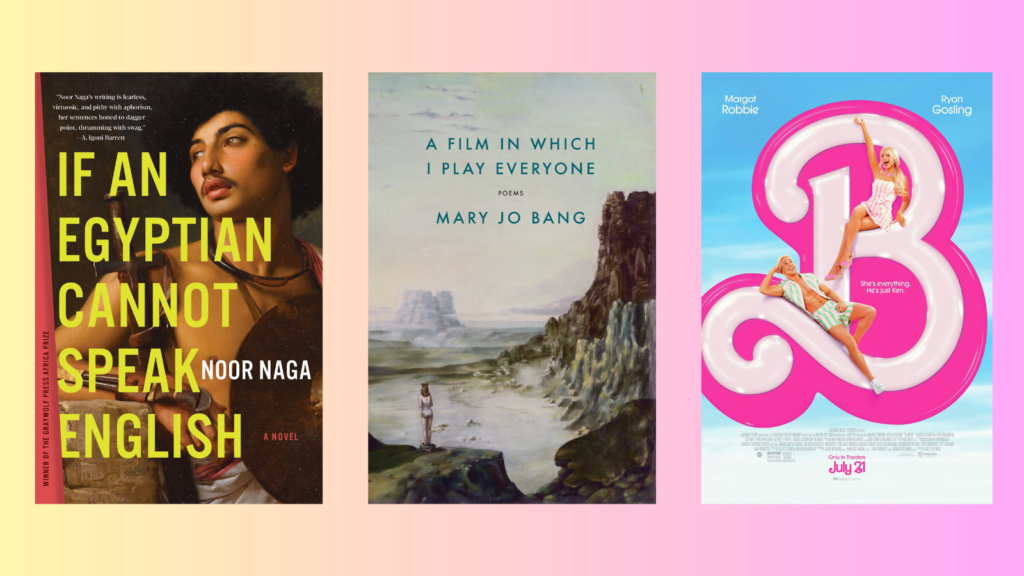

The title of Mary Jo Bang’s new book (Graywolf, 2023) is a David Bowie quote, but I keep thinking of the Velvet Underground lyrics, “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are.” And the advice adults give you as a kid: “treat others the way you’d want to be treated,” advice that implies a type of interconnectedness, or a oneness of conscience, or a civic responsibility that I could go on speculating about forever.

Our attempts to define ourselves and others: “The background is bipartite. The dividing line / confirms: if you feel like a misfit: you are one.” To fit neatly into a category when we’re meant to be unstable, when there’s so much we don’t know, even as we cling to identity and injustice. What it’s like to be a girl, a woman: “…A girl makes a world / that is odd, bent, inverse…” and “Slowly things get done. Or done to you.” Yet, the poems themselves appear

in neat stanzas, tercets or quatrains, like windows, or couplets, like two broken slats of blinds, flipped up, while the other slats stay shut. I don’t know if I’m looking out or looking in, but the book is disorienting in that way. Each of six sections is prefaced by an ominous crosshair’s symbol.

If this collection were a film, it’d be highly experimental, and it’d be a film to feel, more than see. Sometimes there are close-ups but sometimes we’re cosmic, an exercise at letting attachment and detachment, empathy, and anger co-exist. There are hints at a composition and setting, but they’re always abstract and blurry. “In the Movie of My Unraveling Mind,” Bang begins: “The forest opens wide then closes once I’m inside and looking up.”

Hollywood, a metaphor for perfection, is supposed to be this big thing, this dream—the money and the glamor. But through an oscillating scope of reflection, Bang points out how narrow the framing of a film lens can be, how

self-concerned we are yet still, self-doubting. The poet speaker offers small bits of information throughout—the texture of her therapist’s dresses, details of architecture, twists of dreams, and even a few theses on photography, psychology, philosophy. In “Camera Lucida,” she writes: “Barthes appears to over-read the social / aspects of photographs while / under-reading the formal elements.”

Since photography, always a democratic medium to start with, now genuinely belongs to everyone, we are watched, and we are watching, waiting, rationalizing ourselves and everyone else around us. In the collection’s title track, Bang writes, “I’m making sense all the time of senseless endings / A day is as long as the time it takes / for the mind to consider life and death countless times. / Which must make a day plus a night a highway…” Things don’t really add up, but they do compile into peculiar, vibrant landscapes, and timescapes, memories as moving pictures written on the page.

Q: Who is the speaker?

A: Barbies are us.

Where every night is girl’s night.

Barbie, delirious with pink fluff and the little objects of my youth, is a clever rendering of the intersections between consumerism, which targets femme people above all, and our nostalgic investment in pop culture. It’s true the movie is an ad (that worked), produced by Mattel, but it’s difficult to ignore the ways in which it intentionally fills a gaping hole in the Hollywood film portfolio, where, if women want to be “in” on the joke, it’s because we’re flexible, imaginative, resourceful, not because we’re in in. Sometimes we’re explicitly out. This movie, however, is an inside joke for feminine people who are angry and therefore maintain our sharp wit, who, in our youth, were things and knew things that we didn’t have language for, who kept secrets, were afraid and delightfully strange, had some kind of desire to break out.

Barbie plays with in-between spaces; it’s only Gloria’s speech about the dizzying experience of being flung

patriarchy Ken brings back from The Real World. The pink road to and from Barbieland, where Barbie first belts out the Indigo Girls’ song, “Closer to Fine,” a suggestion for how to go easy and/or quit the pursuit of extremes altogether.

In theaters, Barbie creates a space to knowingly smirk but also to mourn. Barbie’s sudden, “irrepressible thoughts of death” confirm the paradox of being human: we want it to go on forever, but if it did, the stakes would be lower and nothing would matter. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned the art of crying for myself, not self-pity, but mourning for earlier versions of myself, now gone, who sensed something was wrong or annoying or not appropriate but had no definitive proof and didn’t check with anyone, that type of quiet helplessness. As a vigilant girl, then teenager, then adult, it builds up. Some experiences can be laughed off, like men giving repetitive speeches about the merits of certain songs or films (Presidency Barbie slyly uses The Godfather to distract Kens). Less funny, your boyfriend trying to comfort you by playing guitar when you’re mourning your abortion (Britney, not Barbie, but still). “I’m sad again, don’t tell

my boyfriend, it’s not what he’s made for,” sings Billie Eilish on the track that haunts its way, now through social media, but originally, through the film.

By the time the Barbies team up to reverse patriarchy in Barbieland, Stereotypical Barbie’s perspective has widened to the point that she has no sense of self anymore and can’t go back to being the object. “I don’t really feel like Barbie anymore,” she tells Barbie creator, Ruth Handler, and the two walk arm-in- arm into watercolor light with no edges, just horizon. Ruth shows her a montage of photos and home videos of women from The Real World, through which she continues to warn: It’s messy. Do you want that? You’ll meet connection and her mother, loss. It’s not fair. Then, you end, and so does everyone else. Do you want that?

Barbie asks Ruth, “So being human’s not something I need to…ask for or even want…I can just…it’s something that I just discover I am?” Yes. More like wind, the opposite to hard drawn.

In the end, Barbie gets a pap smear (probably) and Barbies decide they can share some of their power with Kens, but only some.

Q: Who is the speaker?

A: The one who gets to speak.

The desire to get power, the consequences of being unempowered, the guilt one feels over having power, the fact that power can make people woefully out of touch. And finally, the impossibility of power, which doesn’t mean power isn’t real. It is real, but there’s always a context in which to lose it.

An Egyptian-American woman moves to Cairo to get in touch with her heritage, where she meets a boy from Shobrakheit, and they fall into a romance full of lust and judgment. In the first two of three sections, each separated by a black page, a curtain, the two take turns as the speaker, sharing their own self-analysis and continual analysis of the other, sharing their private notes and unsaid grievances. Poetic questions loom, tense and unanswerable: “If you are competing to lose, what do you win if you win?” and “How far can you run from home before you have to face what your father has done?” First, he has the power because Egypt is his home, and she speaks Arabic the way a visitor would.

Then, she has it because she’s American, speaks English, and he doesn’t, and the years-earlier events of the Arab Spring aren’t just photos from a newspaper. He is palpitating with disillusionment. But he’s a man, so he violates her, and she is playing a part, and since she can leave Cairo any time, she doesn’t see it as real, like she’s still watching the news. He’s poor and an addict, treats her like an object, stalks her, wants control. Then he dies trying to attack her new boyfriend, and she feels guilty. Ultimately, as she considers him in context, she can’t muster up the conviction to blame him. And she thinks if she had been more careful of her power, he wouldn’t have had to die.

In the third section, written in script format, we find the author herself sitting in a writing workshop, adhering to the “gag rule,” which requires that writers remain silent while, in this case, the other writers in the workshop project their own trauma and privilege onto her writing, one up each other’s suffering, and fail to take her word for it. We sit in workshops and people tell us what we wrote doesn’t make sense,

(I’m sure I’m guilty too) and we’re thinking 1. But this is what happened. and/or 2. But this is a metaphor of what happened, so this is mostly what happened and/or 3. But this is what should have happened and/or 4. Suddenly, we’re trying to make sense?

But after reading, you and I will be holding the book by the author, with the author’s name. Her perspective, undermined with care by her own concerns. A question about the responsibility of getting the last word and the intentions that proceeded. A question about why the question of who gets to tell what story is more complex than it seems. Truth telling vs. its ethics, or wanting to appear a certain way vs. wanting to not cause harm. How much privacy do we grant writers and how much autonomy?

Ultimately, if a singular question is a curtain, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English pulls back that curtain to reveal what kind of dimensions inquiry takes on in the way, way beyond, where the point of asking is never one answer.

Katy Scarlett is an educator, poet, and essayist from New Jersey. She earned her MFA in creative writing from Virginia Commonwealth University and her MA in art history from Hunter College, CUNY. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Hunger Mountain, Cimarron Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, CRAFT, and elsewhere.