By Sebastián Encina, Collections Manager

It’s July, a time when the country gathers together to celebrate the independence of the United States. The days leading up to and following the 4th of July are filled with patriotic images. These include the flag, depictions of Uncle Sam, fireworks, and, of course, the eagle. A long-standing symbol of America, the eagle has been used in a number of depictions over the years. We see it on coins, on stamps, on posters, in toys, in movies, even at the grocery store and at restaurants. It is a proud symbol, one that carries much weight and meaning.

The eagle as a symbol of power has a long tradition in other cultures, one that goes back thousands of years. It is often depicted as the bird of Zeus, the king of gods in ancient Greek culture, where we see it in a variety of forms, including textiles and figurines. The Romans carried it forward with their depictions of Jupiter. The power of Jupiter equaled the power of Rome, and where the Romans traveled so did eagle imagery. It appeared on coins, figurines, military paraphernalia, and sculptures.

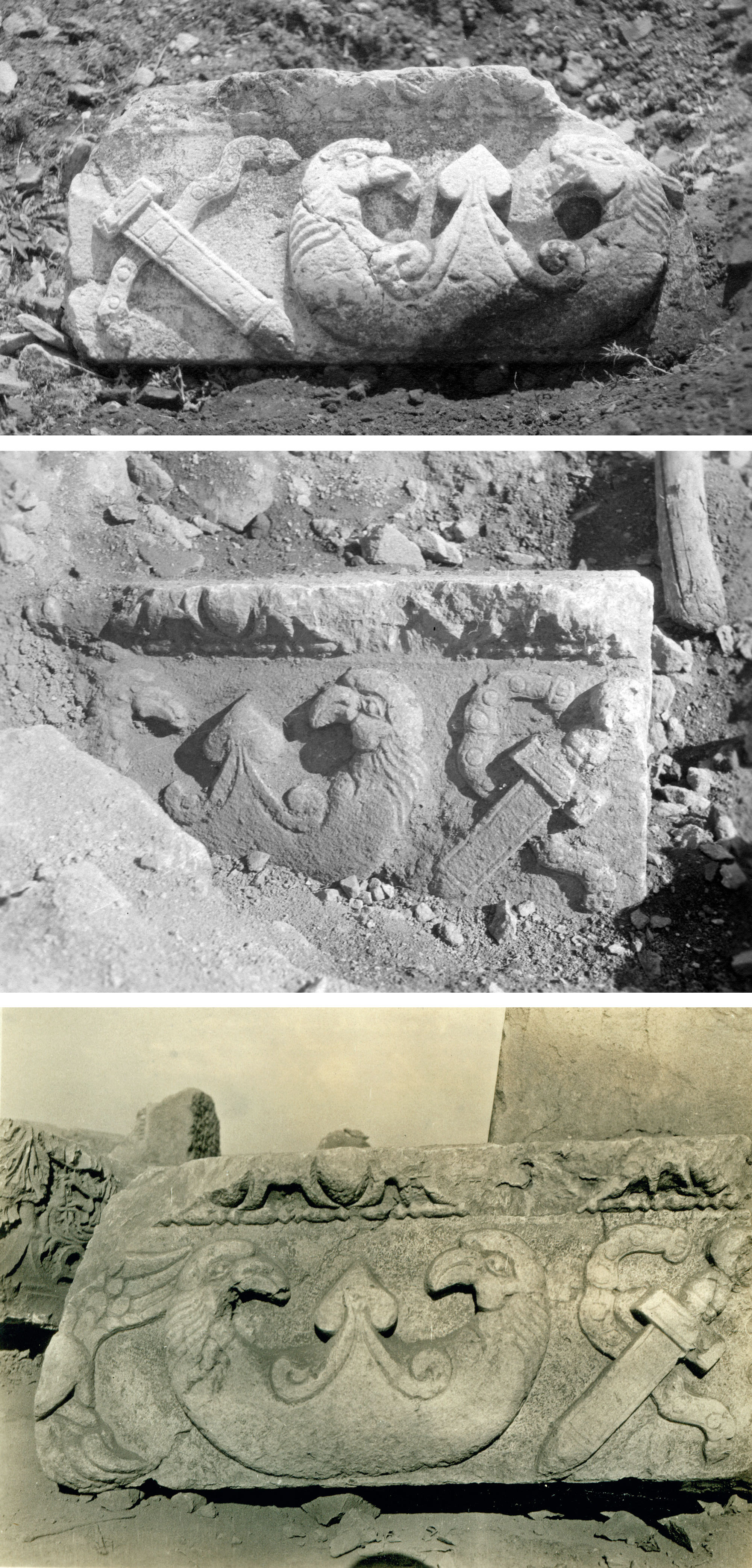

For this month’s “From the Archives,” we present a few images of eagle sculptures found by the University of Michigan’s 1924 expedition to Antioch of Pisidia, in modern-day central west Turkey.

These carved relief blocks are from the frieze of a monumental arch located at the entrance of the city. It was built by the people of Antioch and dedicated to the emperor Hadrian and his wife Sabina in commemoration of Hadrian’s tour through Asia Minor in AD 129. The arch would have presented a monumental welcome to the emperor as he entered the city.

Established as a Roman colony under Augustus in 25 BC, Pisidian Antioch was the oldest and most strategically important of the Roman colonies in Pisidia, but by the Hadrianic period it was only one among many prosperous cities in Asia Minor. Civic competition among cities within Roman provinces was fierce; a visit by the emperor was a prestigious event that could raise a city’s stature in relation to its neighbors and within the imperial administration.

The form and decorative program of the Arch of Hadrian and Sabina contains numerous references to another monumental structure in Antioch, the Arch of Augustus, erected in 2 BC during a period of intense imperial investment in the city. “Creating a new version of the [Arch of Augustus] at the very entrance to the city and dedicating it to Hadrian would announce the city’s dedication to the emperor” (Ossi 2011, 101).

So as we celebrate this 4th of July, we can remember how, nearly two thousand years ago, the people of Antioch, a mixture of Phrygians, Greeks, and Romans, employed the eagle — the very symbol of America’s hard-won independence from British rule — to strengthen their ties to the imperial power of Rome.

******

For more about the archaeological expedition to Pisidian Antioch, the viewer is invited to visit Building a New Rome: The Imperial Colony of Pisidian Antioch. In this online version of the special exhibition, held at the Kelsey Museum in 2006, curator Elaine Gazda and her team make use of archival materials to present Antioch in new and refreshing ways. The exhibition catalog of the same title is available for purchase.

******

Ossi, Adrian J. 2011. “The Arch of Hadrian and Sabina at Pisidian Antioch: Imperial Associations, Ritual Connections, and Civic Euergetism,” in Elaine K. Gazda and Diana Y. Ng, eds., Building a New Rome: The Imperial Colony of Pisidian Antioch (25 BC–AD 700), pp. 85–108. Kelsey Museum Publications 5. Ann Arbor: The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology.