From the Archives #64

By Sebastián Encina, Collections Manager

The “From the Archives” blog post from this past January featured the Kelsey Museum’s first method to track newly acquired materials. The ledger, very similar to ones used at other museums, is a line-by-line book of every item the museum accessioned, whether the item came via donation, excavation, or purchase. The ledger, though limited, provided a wealth of information. Each item was given its own unique inventory number, under which was listed as much information as was known: collection date, acquisition date, source, and any other relevant information. In some cases, ledgers would include drawings of the item, or drawings of special features.

As useful as a ledger is, there are several downsides in using this as the primary means of tracking objects. For one, the information captured is based on the time someone has to enter the information by hand. Second, it does not afford a researcher a way to search the collections. Since everything is entered as it was acquired, there is no way to search across or see a grouping of similar items. In time, a card catalogue was created at the Kelsey to help with searching and grouping, but these functions were limited.

These days, museums employ many tools to track their collections. At the heart of this for most museums is a database. There are many options, and a museum can choose a system depending on its own set of needs. Even these evolve over time; the systems available in the early days are not as powerful or sophisticated as newer systems.

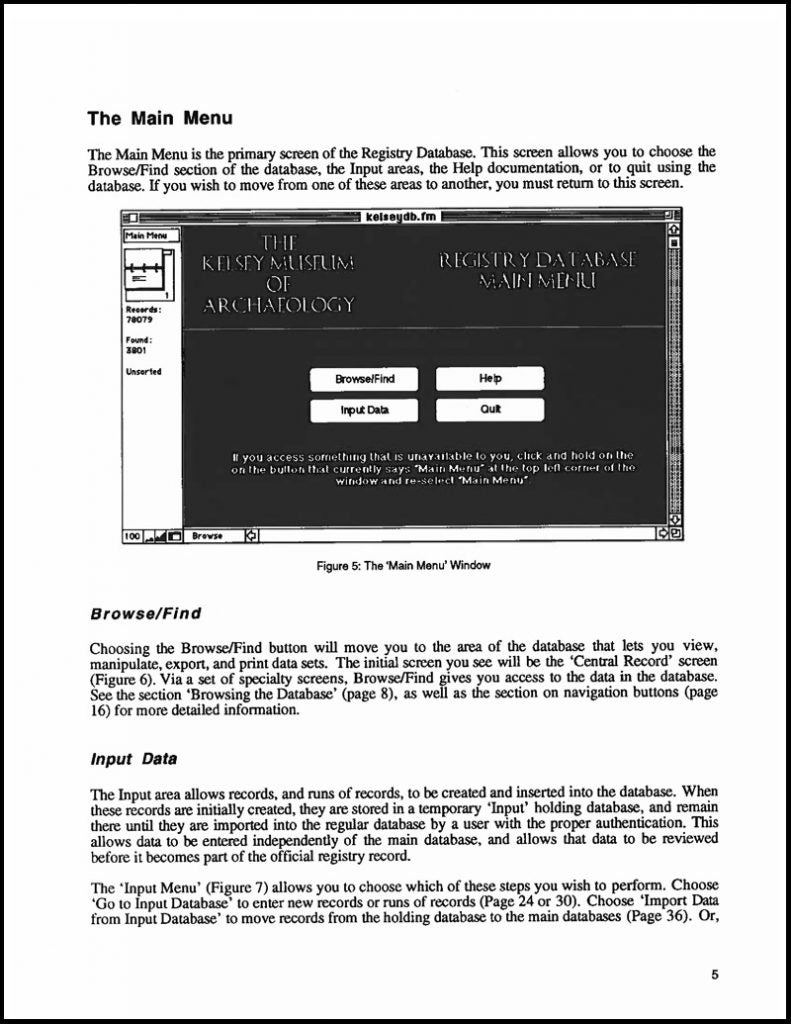

For this month’s “From the Archives,” we present an early version of the Kelsey Museum database. Though not the first database used here, this FileMaker Pro database from 1996 still represents an early foray into the digitization of our collections. At this time, much of the database was text-based. Interns, volunteers, and staff would enter basic information from the ledgers or card catalogues into the database. As computers back then were so limited in space, it was difficult to include more information, let alone images. The pages of the Registry Database Manual presented here show how limited the database was in terms of information and presentation. Reports had to be written into the system, as customization was not possible.

Though databases now are faster, more powerful, and capable of so much more, it is important to acknowledge where we started and how we used to work with our information. In much the same way that excavation records dictate future research, so too does the way a museum captures information inform future research. Non-standardized text fields meant similar information was captured in a variety of ways (ceramics vs pottery, fragment vs sherd), causing incomplete searches.

It is important for museums to not only track the history of their collections, but also the way they work. Museum staff spend a lot of time decoding past actions and decisions, often with very little information to begin with. Being able to go back and find old records such as these database files inform us why certain artifacts are catalogued in certain ways. Having that history represents a full picture of the care of collections, how they have been handled and used. Knowing where we have come from at all levels will make for better-informed decisions in the future.

From the Archives #64 Read More »

BY SEBASTIAN ENCINA, Collections Manager, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan

BY SEBASTIAN ENCINA, Collections Manager, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan