News from the Conservation Lab — Laurel Fricker!

By Caroline Roberts, Conservator

This month’s Conservation blog post serves as a send-off for Laurel Fricker, our wonderful graduate student researcher for the Color Project. Laurel is finishing her third year in the IPCAA program and will be spending her fourth year at the American School in Athens. We are so excited for her, and so sad to see her leave! We wanted to feature Laurel once more on the blog before she heads off on her Greek adventures and get her take on her experience exploring ancient polychromy at the Kelsey over the past year.

Carrie: Hey, Laurel! I love that you are as excited about ancient color as we are, however, I know your research interests go beyond this topic. Can you tell folks more about them?

Laurel: I primarily study houses and households in ancient Greece and I am really interested in exploring questions related to the daily lives and identities of the inhabitants of ancient Greek houses. To do this, I hope to take an object-focused approach where I will connect objects uncovered in houses with their findspots to see how much can be said about the different activities that took place in houses and what can be determined about the people who did those activities.

C: Awesome. So what drew you to the Color Project? What were you hoping to learn?

L: I have always been interested in the idea of exploring color on ancient objects, but I was never afforded the opportunity to do so until the Color Project. I was completely blown away when I was first told that ancient sculpture was originally brightly painted, as many of the objects held in museum collections and presented in textbooks are not often discussed in terms of their original color. I played with the idea of researching ancient color for a term paper during my master’s degree, but unfortunately it was not encouraged, and I did not pursue the topic any further. When I saw the announcement that Kelsey Museum conservators Suzanne and Carrie had won this incredible NEH grant in December 2020, I knew I had to reach out and see if I could get involved. Thankfully they said yes!

I don’t really remember what I was hoping for when I first joined the project; I just know that I wanted to learn as much as possible, gain new skills, and develop deeper connections with the Kelsey Museum staff. I can confidently say that I accomplished all three!

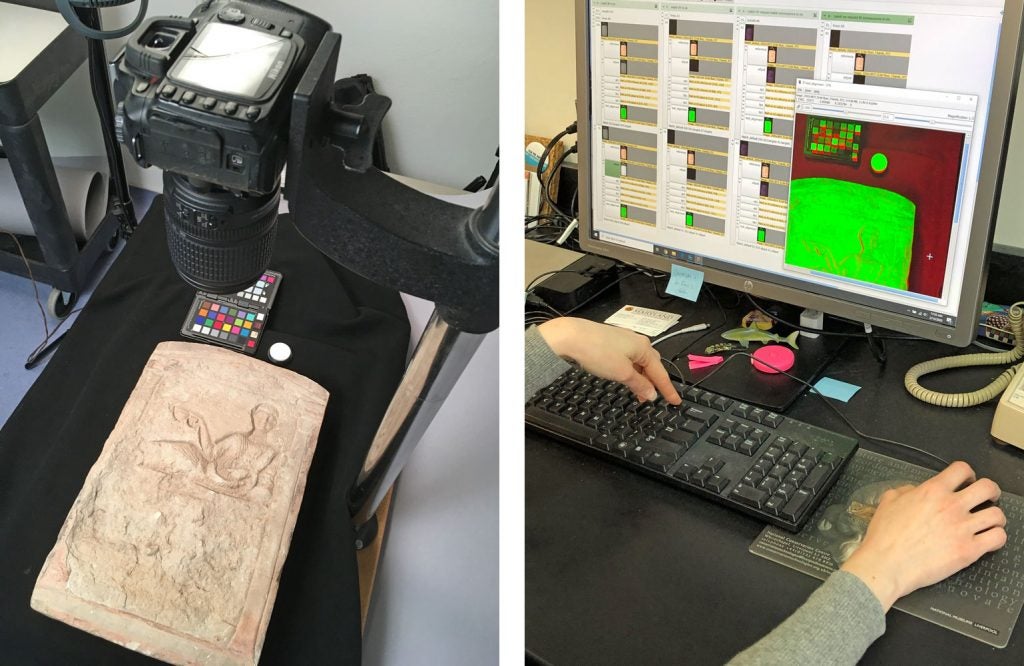

Suzanne, Carrie, and I could not start our work in the lab right away because of COVID restrictions on campus, so the first few months involved a lot of intense reading and research. This was really eye-opening for me! Carrie and Suzanne knew so much already because they had already been doing some multispectral imaging (MSI) of objects in the Kelsey collections and because of Carrie’s work curating the Kelsey Museum’s 2019 exhibition Ancient Color. I, on the other hand, was completely underprepared when I first started; there is a good amount of scholarship discussing different avenues for researching color on ancient objects and what other scholars have discovered through this work and I had a lot of catching up to do! I had not touched chemistry since high school and suddenly all these articles on X-ray fluorescence (XRF) were discussing different elemental compositions of pigments and other articles on MSI were presenting data on different wavelengths of light and what this meant for showing traces of pigments. I was definitely out of my comfort zone at the start, but it has been a lot of fun to see my growth over this year and to have all the articles I read early on start to make sense as I do the work in the conservation lab myself. I have learned a great deal and I am looking forward to continuing this work when I come back from my year in Athens!

C: How many objects have you looked at for the project so far? Which one is your favorite and why?

L: One of the goals of the Color Project is to study about 200 Roman Egyptian objects housed in the Kelsey Museum that have documented excavation contexts from Karanis and Terenouthis in Egypt. My role in the project involved researching the ceramic objects included in the list, primarily figurines from Karanis.

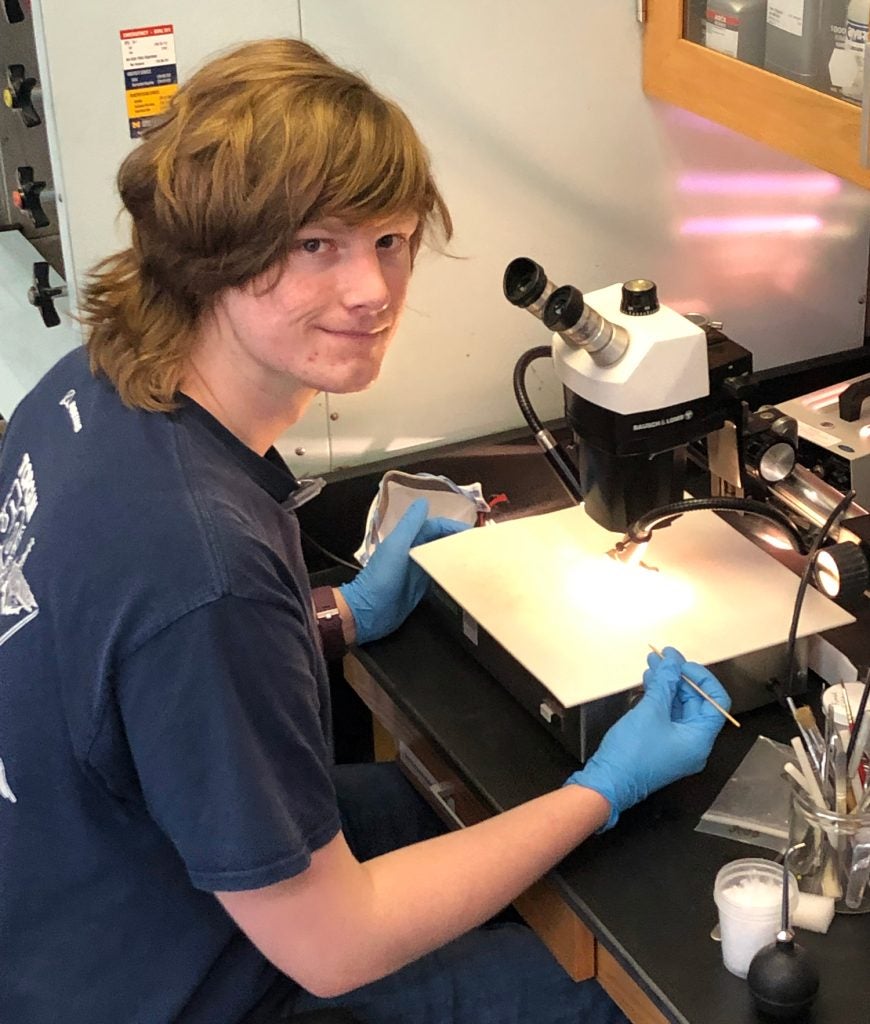

Over the past academic year, I spent around 120 hours in the conservation lab under Carrie’s supervision. During that time, I imaged and analyzed over 35 objects. Studying each object was a multi-step process: capture a condition record photograph, complete an MSI workup, process the MSI photographs, enter the MSI data into the spreadsheet, investigate the pigments with XRF, process the XRF data and enter it into the spreadsheet, record all the data in the appropriate way according to our data-management protocols, and then upload the most important information to the Kelsey Museum database!

Picking just one favorite object is really tricky! So here are two:

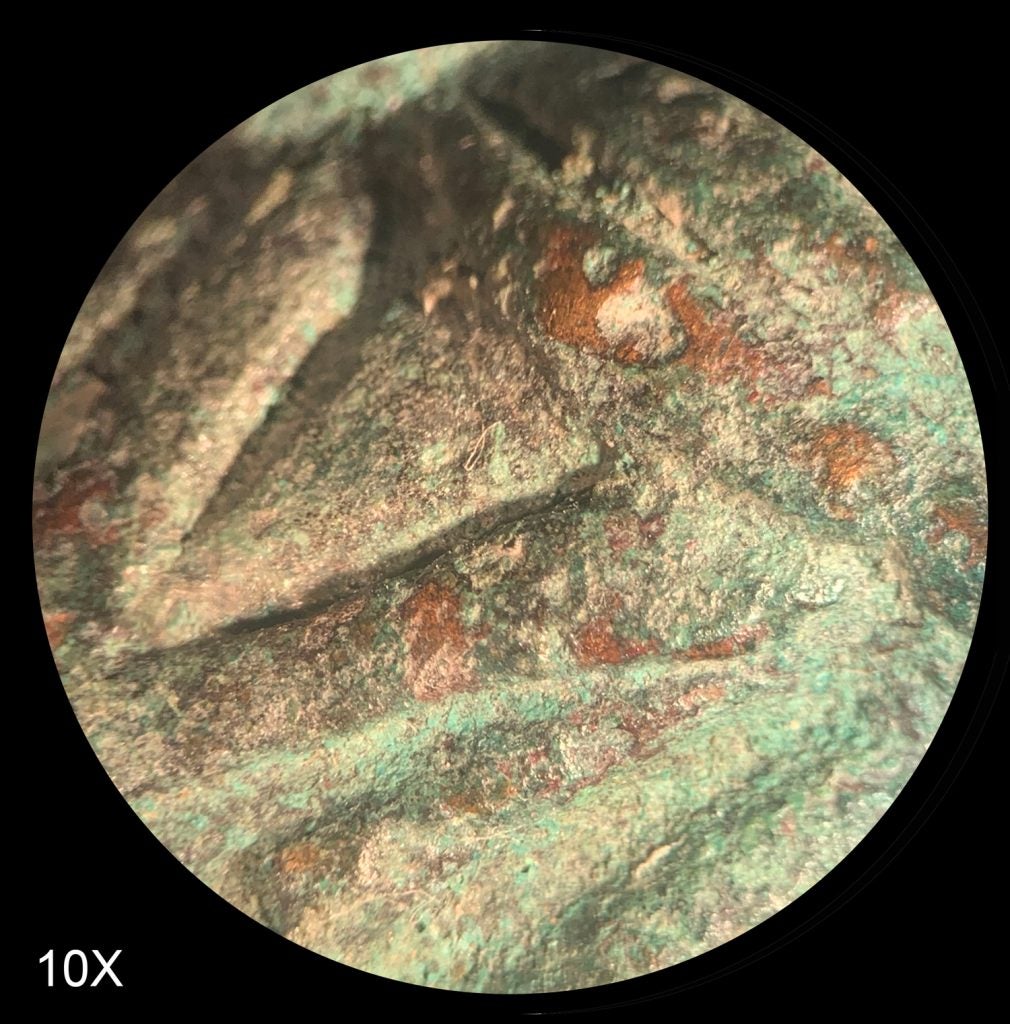

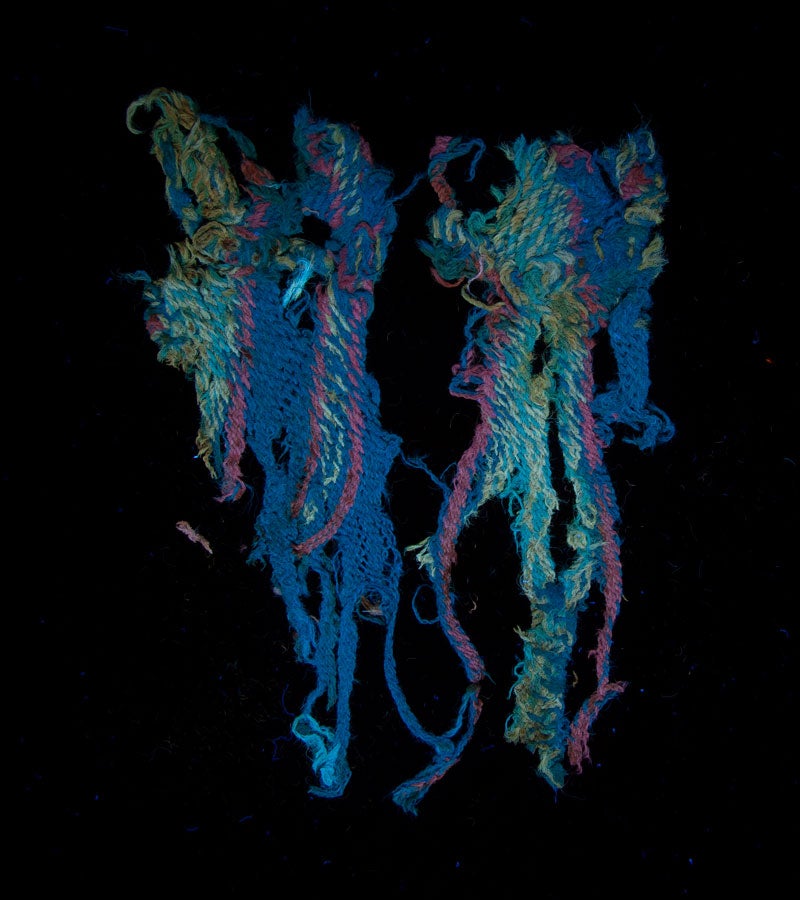

First is KM 6449, a Harpocrates figurine standing next to a stove piled with bread, holding a pot, and leaning on an amphora. Excavated at Karanis in 1935, this figurine is really fun because of the amount of color that has been preserved that is visible to the eye—red and blue on the stove, pink on the amphora and the pot, yellow for the amphora base and in the curly hair, and black dots on the bread and as a ground line. This object was a treat to study because it was incredibly cool to see all this preserved color. However, everything was not exactly as it looked to the eye. In addition to the pink visible on the amphora and pot (a pigment created from mixing red ochre and white), there was a different pink in the crown! This pink was only shown through MSI as the area fluoresced orange under ultraviolet light, meaning it is a rose madder. Then the blue turned out to be Egyptian blue—the MSI infrared image showed the blue area clearly luminescing. I really enjoyed the process of studying KM 6449 and it was one of the first objects where I finally felt confident and that I knew what I was doing!

Second is KM 6578, a figurine of Eros on a swan rising out of waves. When I first joined the project and Suzanne and Carrie were deciding on the list of objects to study, this object was my first request. Sadly, this figurine does not come from a Michigan excavation—it is a purchase—but it is one of my favorite pieces in the Kelsey collection. Eros on the swan is another figurine with a great deal of color preserved and visible to the eye: the swan is white and has a red beak and feet and there are two different shades of purple on the swan’s wings, the waves are blue, and Eros still has a good amount of his skin tone. The purples are interesting because they are likely mixes of red ochre, a white, and differing amounts of carbon black to get the two different shades—this shows that the artists were capable of creating different colors and mixing pigments to get new shades. Also, this figurine had a lot of Egyptian blue present, both in the waves and in parts of the white of the swan, likely included to add depth and shading to the torso of the swan.

I could keep going—there are so many incredible figurines that I have studied this year!

C: I love those two! They both have some of the best-preserved color on any of the terracottas in the Kelsey collection. Can you tell our readers—why do you think it’s important to study color on archaeological materials?

L: I think color is a really important area to study because for too long our interpretation of the ancient world has been one that seems white, monochrome, and dull. But that is not the case; just like today, the ancient world was full of color! The architectural decoration of public buildings, the walls and floors of houses, figurines, votive offerings, pottery, and garments were all decorated and full of color and this fact is still only slowly gaining the attention of scholars. There is still this idea in popular culture that the white marble statues seen in major museums and presented in books are a reflection of notions of perfection and beauty. These ideas are incorrect and can be extremely harmful. I won’t go into detail about this here, but this has been written about by scholars such as Sarah Bond; one of her articles can be found here.

There are many different avenues that can be explored using color, including trade and connections when it comes to the sourcing and creation of pigments, questions of identity and the decisions that go into choosing different colors, and the cultural values and ideologies exemplified by different colors and pigments. Further, as I am interested in the lived experiences of people in the ancient world, every piece of information that helps me better understand their daily lives—including how colorful their surroundings were—is exciting!

C: It’s true that we have so much more to explore on this topic. But looking ahead, are there any cool sculptural or architectural polychromy you’re looking forward to seeing in Athens next year?

L: Next year I will be in Athens as a member of the American School of Classical Studies and part of the program involves site and museum visits all over Greece. While I am sad to be away from the Color Project and figurines in the Kelsey, I am very excited to see if my better-trained eye can pick out more traces of color on different objects on display now that I have a better understanding of the different pigments in use in the ancient world. I am especially excited to see the Peplos Kore and the Kore from Chios again, both on display in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. The two korai have traces of color preserved in their hair and on their garments. These large Archaic Greek marble sculptures are quite different than the small Roman Egyptian terracotta figurines that have been my friends for this past year, but they are just as fascinating. And I am excited to be surprised by color and see traces of pigments when I don’t expect them!

C: Thanks, Laurel! We can’t wait to hear all about it.

News from the Conservation Lab — Laurel Fricker! Read More »