BIG Object Spotlight #1: Interviews with Kelsey Curators and Staff

By Emily Allison, with Janet Richards, Scott Meier, and Eric Campbell

If you have spent any time around the Kelsey Museum in the past several years, you may have heard whispers of the acronym “BIG.” Standing for “Byzantine and Islamic Gallery,” BIG refers to the new, permanent gallery that Kelsey curators and staff are hard at work developing. Although the opening of this gallery is still a few years away, a series of “Object Spotlights”—available over the coming months—will allow visitors to receive a small sampling of the artifacts and themes that are yet to come. The first of these Object Spotlights was installed in late June and will be up through the end of October, around which point a new group of artifacts will be available to view.

To learn more about progress on BIG (and more specifically, the development of BIG Object Spotlight #1), I spoke with Janet Richards, Scott Meier, and Eric Campbell—each of whom played key roles in making the opening of the first Object Spotlight a success.

Janet Richards, our first interviewee, was the lead curator for BIG Object Spotlight #1. She also serves as the Kelsey Museum’s curator for Dynastic Egypt and a professor of Egyptology in U-M’s Department of Middle East Studies.

Emily: To start, can you talk about the Byzantine and Islamic Gallery? Those who are intimately involved with the Kelsey Museum have been aware of the gallery’s ongoing development for quite some time, but how would you describe the gallery and its goals to an external audience?

Janet: In this new permanent Byzantine and Islamic Gallery (BIG), we’ll showcase the Kelsey’s Byzantine and Islamic collections of art and material culture, as well as artifacts relating to early Judaism. We’re lucky to have substantial support from the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts for this work. This gallery—initial planning for which has been overseen by a Kelsey curatorial team with input from Paroma Chatterjee, our History of Art colleague who served as a visiting curator in 2020–2021, and an advisory committee of experts in and beyond the University—will fill a critical gap both geographically and chronologically in our new-wing displays. The project gives us the opportunity not only to consider artistic and archaeological remains of the medieval world in western Asia, the Mediterranean, and northeast Africa but also to highlight how this evidence for the human past resonates with the concerns and lifeways of our modern world.

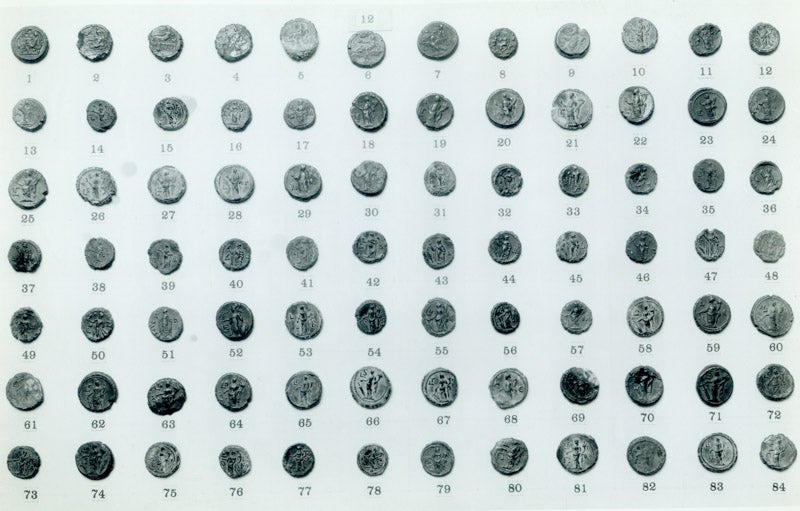

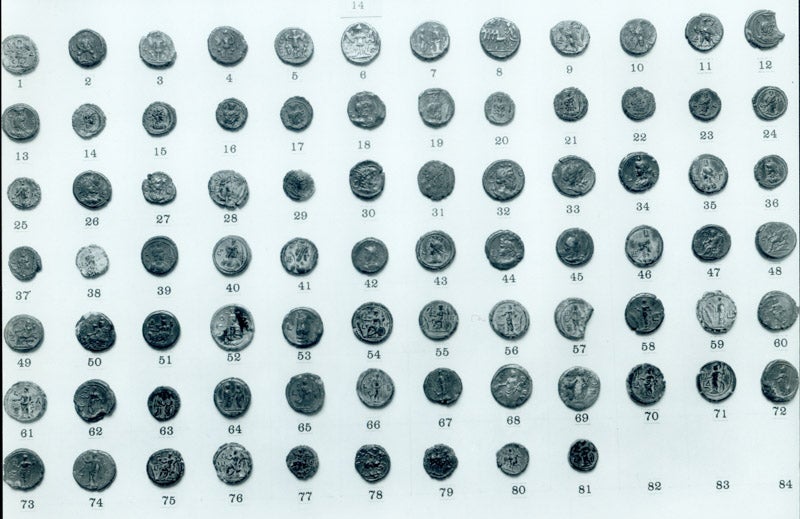

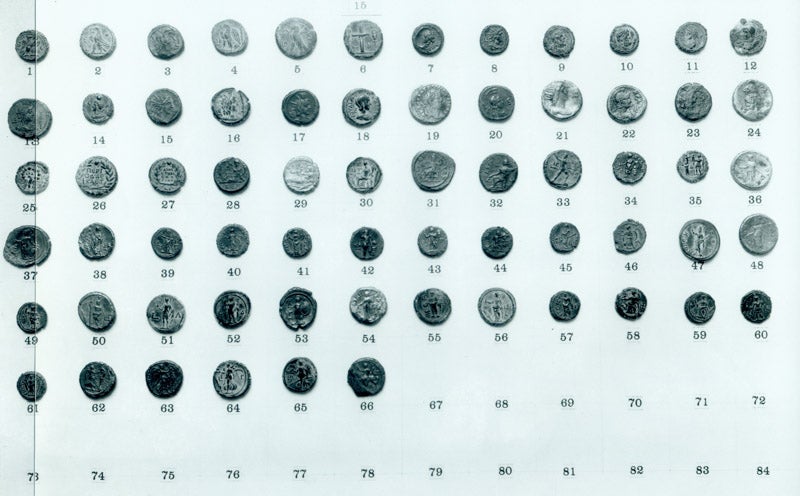

We’re committed to avoiding traditional boundaries and instead exploring the long-term cultural and intellectual interrelationships of these different regions and cultures, through themes such as travel, piety, soundscapes, animals and humans, and the expression of status and identity through material culture. And we can bring to the mix a strong sense of context, thanks to Kelsey excavations at numerous sites relevant to this installation. We want to give our visitors a sense of real people and their commodities sharing and moving between lived landscapes and intercultural dialogues, all materialized through a wide array of media—coins, textiles, visual productions, glassware, domestic productions, architecture, and spaces.

Emily: What is your role in the development of BIG, and more specifically, in the development of BIG Object Spotlight #1?

Janet: I’m one of the Kelsey faculty curators; my own work is in the Middle East, specifically on the Egyptian Nile Valley of much earlier periods. For 2022–2023, I was acting project manager and lead curator for the Byzantine and Islamic Gallery project. Exhibitions, especially permanent galleries, are a multiyear process; so with the curatorial team and Scott Meier (the Kelsey’s exhibits preparator), I developed the idea of a series of BIG Object Spotlight installations to give Kelsey visitors insight into the process as it unfolds. In this way, we can give visitors and students access to key artifacts and themes to watch for in the eventual permanent gallery.

Even a comparatively compact installation like this requires the collaboration of a village! We owe BIG Object Spotlight #1 to the efforts of Kelsey professional staff: Scott Meier, Eric Campbell (graphic designer), Emily Allison (editor), Michelle Fontentot (collections manager), Carrie Roberts and Suzanne Davis (conservators), and Tamika Mohr (chief administrator). The curatorial team included Nicola Barham, Terry Wilfong, and myself; curatorial assistant and IPAMAA graduate student James Nesbitt-Prosser (who sole-authored the in-depth content on the in-gallery monitor); and our new visiting curator Christy Gruber of the U-M History of Art Department, who generously shared her expertise even though she was on sabbatical. Our wonderful Kelsey docents, in a session I had with them and Stephanie Wottreng Haley (community and youth educator), came up with the idea of the colorful map you’ll see throughout the exhibition!

Emily: Can you walk us through some of the artifacts featured in BIG Object Spotlight #1? Why were they chosen? What do they tell us about the ancient and medieval Byzantine and Islamic world?

Janet: This installation highlights three different categories of artifacts in our collections, three different media, three geographic areas of the ancient and medieval Middle East, and an assortment of our key themes.

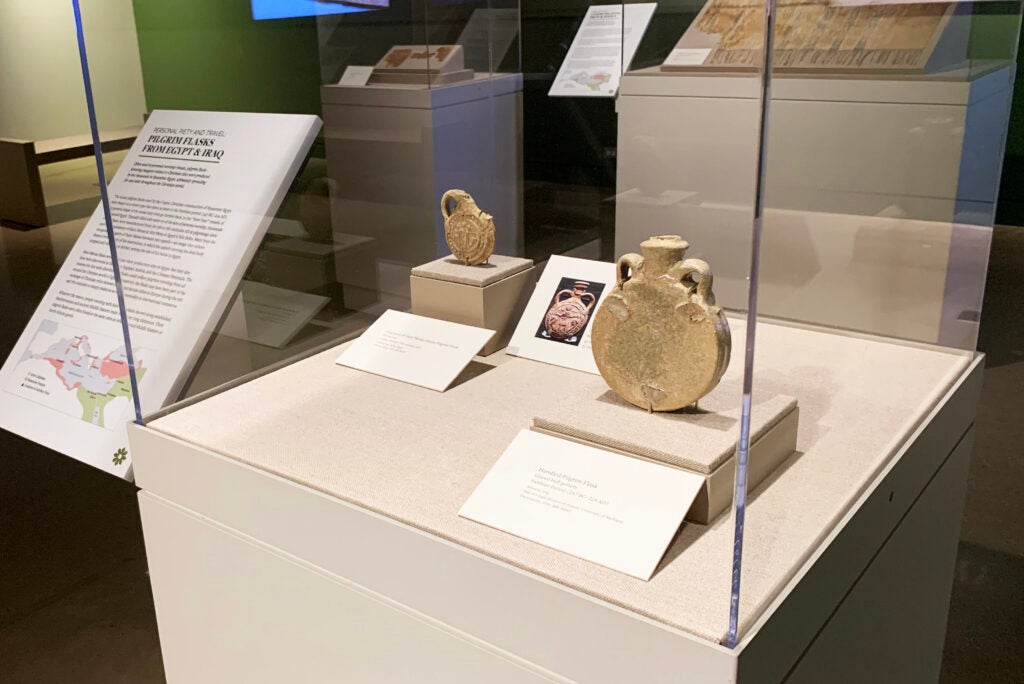

Two ceramic pilgrimage flasks (visible at left; KM 88209 and KM 30043), one from Egypt and one from Iraq, are a type of object produced from the 1st century BC and then manufactured in the thousands from the 5th to 7th century AD at pilgrimage sites. Such flasks were either carried by individual pilgrims, circulated among church and secular elites, or simply traded internationally as exotic commodities.

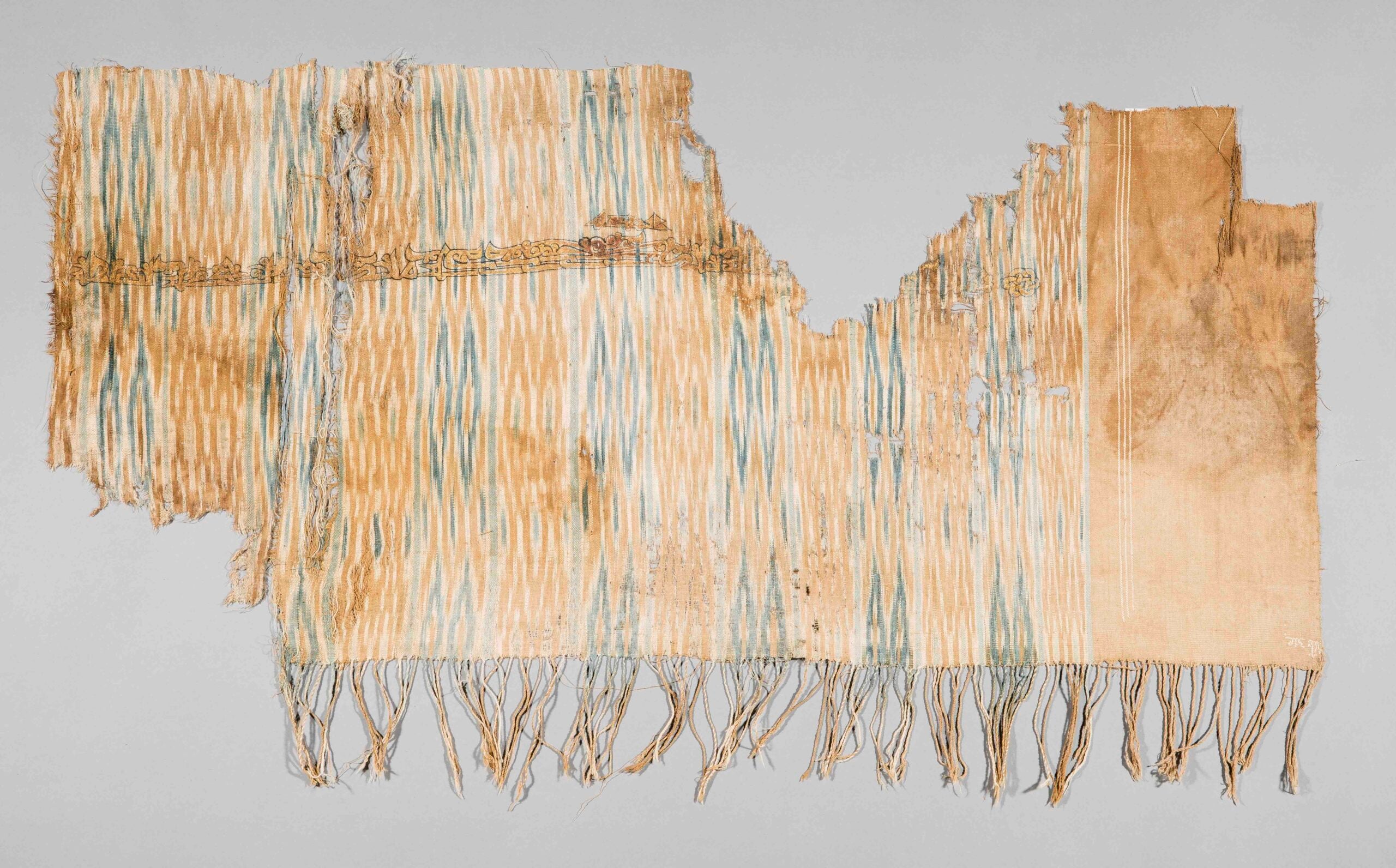

Two inscribed cotton textiles (known as tirāz) are from Yemen and Egypt. They show the visitor two styles of this type of textile: one bears a Kufic (Arabic) inscription reading, “Dominion belongs to Him [God]. Blessing to its owner.” The other is decorated with a colorful motif of rabbits. Such textiles were typically given as gifts to members of a ruler’s court as a marker of social status, but they also had religious significance—in Egypt, tirāz textiles were often used in burial rituals.

Finally, a carved wooden door lintel (see below), dating to the 12th century AD and probably from Cairo, Egypt, is an example of the long history of inscribing prayers on door lintels, a practice that bridges pagan, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions. These materialized prayers, occurring in domestic as well as sacred contexts, not only provided blessings to people passing beneath them but also served the magical purpose of warding off evil. This panel reads, “A perfect blessing, all-inclusive grace, and lasting felicity.”

Emily: What challenges did you face in the development of this initial Spotlight case?

Janet: Choosing colors for the BIG Spotlight space on the second floor of the Kelsey’s new wing. We went into this thinking about deep red, gold, and green—powerful colors of the period across the Middle East. After first trying red on the walls, we did a pivot to trying different (many different!) shades of green, drawing inspiration from a manuscript image Christy Gruber sent us. I’m sure Scott Meier will describe how many different small pots of paint he tried! Christy points out that the final shade used looks like cyprus, appropriate for the geographic emphasis of the gallery.

Other challenges included working out effective content for the introductory and in-gallery monitors (check out Eric’s gorgeous accompanying visuals!) and strategically situating the textiles case in a lower-light area.

In addition, scheduling such an installation is always a process of negotiation with the museum’s different departments to slot in work on this project amid everything else going on at the Kelsey. Scheduling also specifically comes into play for the textiles in particular, the conservation requirements around which are that they cannot be on display for more than four months. So that actually helped us decide on how frequently the BIG Object Spotlight installations will rotate: every fourth months for the next year or so, until we begin the construction phases of the permanent gallery project.

Emily: What are some challenges you foresee in the development of the permanent BIG?

Janet: Scheduling and conservation concerns, as with any exhibition. Cost is always a factor too—not only for expenses related to the installation but also for programming around the project and the gallery. We are fortunate to have the substantial support of LSA for the gallery itself but will be undertaking advancement activities for these related things.

We’ll need to focus intensively in the coming year on nailing down the overall object list (taking into account conservation limits on display of organic objects) and developing the themes and narratives and look of the gallery.

Emily: What other artifacts or themes can we look forward to in subsequent Object Spotlights?

Janet: Each of these will be lead-curated by different people and poll different audiences for ideas about the kinds of objects to display. Next up is Christy Gruber, who is already advanced in her planning for Object Spotlight #2, which will open sometime in November!

As Janet pointed out, the creation of any exhibition—even one with a handful of artifacts like this one—takes a village. Next up is Scott Meier, the Kelsey Museum’s exhibition coordinator, who oversaw the development of the physical space in which the Object Spotlight resides.

Emily: What is your role in the development of BIG and the first Object Spotlight?

Scott: I was responsible for the design and fabrication of the physical space of the gallery. One of the driving forces was to give the visitor a sense of what is still to come once the actual gallery is built. As we continue the Object Spotlight gallery, I would like to see it grow into more of an informational hub for the visitor to not only learn what is happening with BIG but also provide feedback for us about different design ideas.

Emily: Can you talk about the redesign of the Kelsey Museum’s second-floor galleries?

Scott: We are at the very early stages of the redesign, but one of the things we would like to do is create a more open feeling to the galleries so that there is an interplay between them, both in content and visually. We want to convey the message that there was crossover in relationships and time periods.

We are also looking to use color a bit more than in other previous galleries to convey the various cultures. It is still early, but this may provide an opportunity to introduce totally new graphic branding for the permanent galleries.

Emily: What considerations did you keep in mind while prepping the space for the installation of BIG Object Spotlight #1? What challenges did you face?

Scott: The biggest consideration that had to be dealt with was lighting. The two textiles (see below) require low light—five footcandles—so to achieve this without making the gallery look underlit, I had to lower all the light that led up to or was around the textile cases so that the visitors’ eyes could adjust by the time they reach the textile cases.

The biggest obstacle I faced was getting the correct color palette. Because color is going to play a vital role in the new gallery, I wanted to be sure what was represented was accurate as well as palatable to the visitor. What looks good as a small sample doesn’t always read well as a painted wall. It took about 18 samples painted on the wall and three complete gallery paintings until we were happy.

Emily: What are some goals you have for the physical final product of the Byzantine and Islamic Gallery? How will it differ from, or be similar to, the Kelsey’s existing gallery spaces?

Scott: As I mentioned before, we hope to have more interconnected galleries in the future. In terms of design, it is still early, but due to earlier conversations the Exhibition Committee had, I think we are going to walk a fine line between having the gallery reflect the culture via color and graphics without crossing over into trying to be an overly immersive experience.

I would like to make the actual case design and case layout very similar to what we already have so the transition is seamless. However, there are numerous opportunities to update the look to reflect the new gallery. One of these opportunities is addressing potential lighting issues with the artifacts. I am exploring drawers that have motion-sensor lighting that goes on when the drawer is pulled out. If we find this does work, I hope we can take this technology to our existing drawers that are difficult to view because of low light.

I am also hoping we can introduce more interactive exhibits to the new Byzantine and Islamic Gallery with an eye toward adding interactive opportunities in the other permanent galleries.

Finally, I turned my questioning to Eric Campbell. As the Kelsey Museum’s graphic designer, Eric also played a major role in the visual final product of BIG Object Spotlight #1.

Emily: Can you describe your role in the development of Object Spotlight #1 and BIG more generally?

Eric: I am responsible for designing the overall look of the gallery (along with Scott), as well as creating the panels, videos, signage, and miscellaneous collateral.

Emily: What are some challenges you faced while working on the BIG Object Spotlight #1 materials (if any)? Are there any challenges you foresee in the development of future Spotlight cases and, ultimately, the permanent Byzantine and Islamic Gallery?

Eric: Working on the BIG Object Spotlight was not particularly challenging, although the delicate nature of some of the objects—textiles specifically—make displaying them difficult. For future spotlights, and the permanent BIG, we will have to get creative with how we present these objects.

Emily: Do you have any goals for the visual final product of BIG?

Eric: In designing the visual look of the BIG, I hope to push past the subdued museum design that is commonplace. I want to incorporate colors, patterns, and textures from the Byzantine and Islamic world to bring drama to the gallery.

If you have not had a chance to see the first Object Spotlight in person, there are still a few weeks yet left to visit before its deinstallation. And of course, the second Object Spotlight, curated by Christy Gruber, will be up before too long, allowing visitors to view a new thematic grouping of artifacts.

Thank you to Janet, Scott, and Eric for taking the time to discuss BIG and Object Spotlight #1 in detail—we look forward to seeing more in the coming months and years!

BIG Object Spotlight #1: Interviews with Kelsey Curators and Staff Read More »

On this day, in 1929, Oleg Grabar was born in Strasbourg, France. Today would have been his 92nd birthday.

On this day, in 1929, Oleg Grabar was born in Strasbourg, France. Today would have been his 92nd birthday.

Associate Research Scientist

Associate Research Scientist