The Kelsey welcomes visiting scholar Dr. Blondel

By Malloy Bower

The Kelsey gallery cases are filled with ancient artifacts from the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions, with more artifacts available to the public in drawers below the cases. A visitor might be overwhelmed if their goal is to experience every object on display! The objects in the gallery, however, represent a small portion of the collections at the Kelsey due to the limitations of display space. The remainder of our over 100,000 object collection resides in collections storage.

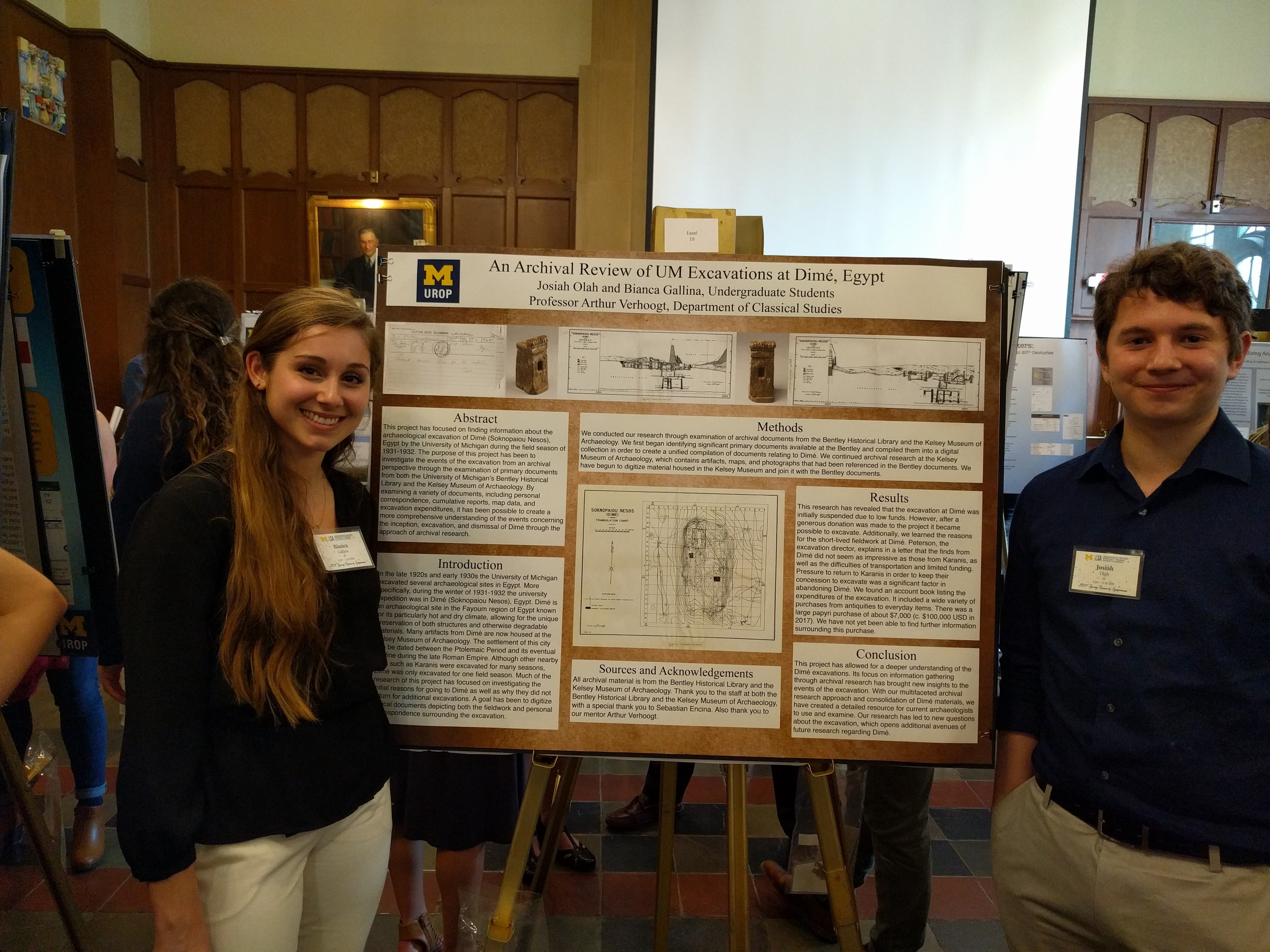

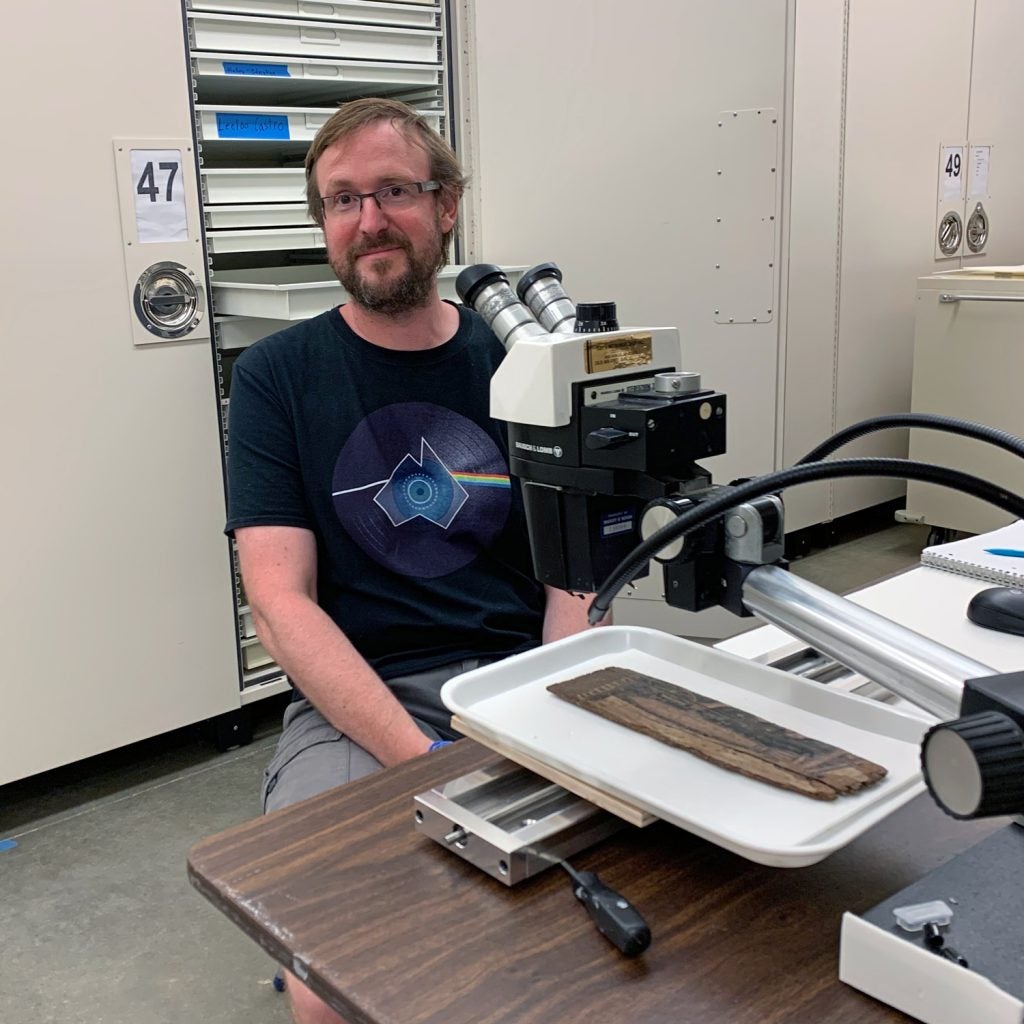

There are numerous reasons why certain objects remain in storage, but their potential for research and adding to our knowledge of the ancient Mediterranean and Middle East is not one of them. Researchers from all over the world travel to Ann Arbor to study the collection, each researcher approaching the objects with unique questions about the people who created, owned, and used the objects. In July 2022, researcher Dr. Francois Blondel from the University of Geneva spent several weeks at the Kelsey collecting tree-ring data from wooden objects excavated in Egypt that date to the Roman period (1st century BCE–5th century CE).

Using a binocular microscope and measuring table, Dr. Blondel measured the distance between tree rings observed on the wooden objects (including KM 88723, featured in June’s Ugly Object blog). With each press of a button to record the measurement, software, connected to the measuring table, creates (or draws) the growth curve of the wood (or its growth pattern) as it goes along. The resulting curve characterizes all the variations of ring widths in these ancient artifacts crafted from ancient trees. Dr. Blondel repeated this process at least three times with each object to obtain the most complete sequence possible and also to compensate for possible measurement errors due to the lack of ring legibility on some complex objects. This data will then be compared to a database of tree-ring measurements and interpreted by Dr. Blondel in a future academic paper to help date the objects. This process of using the growth rings of trees to date objects is called dendrochronology.

We look forward to what his research uncovers about the ancient world and its people, and how the objects in our collections contribute to his findings!

The Kelsey welcomes visiting scholar Dr. Blondel Read More »