Writing a dissertation on the archaic Forum Boarium

BY ANDREA BROCK, PhD candidate in the Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology, University of Michigan

“Every journey begins with one step.” — my mom

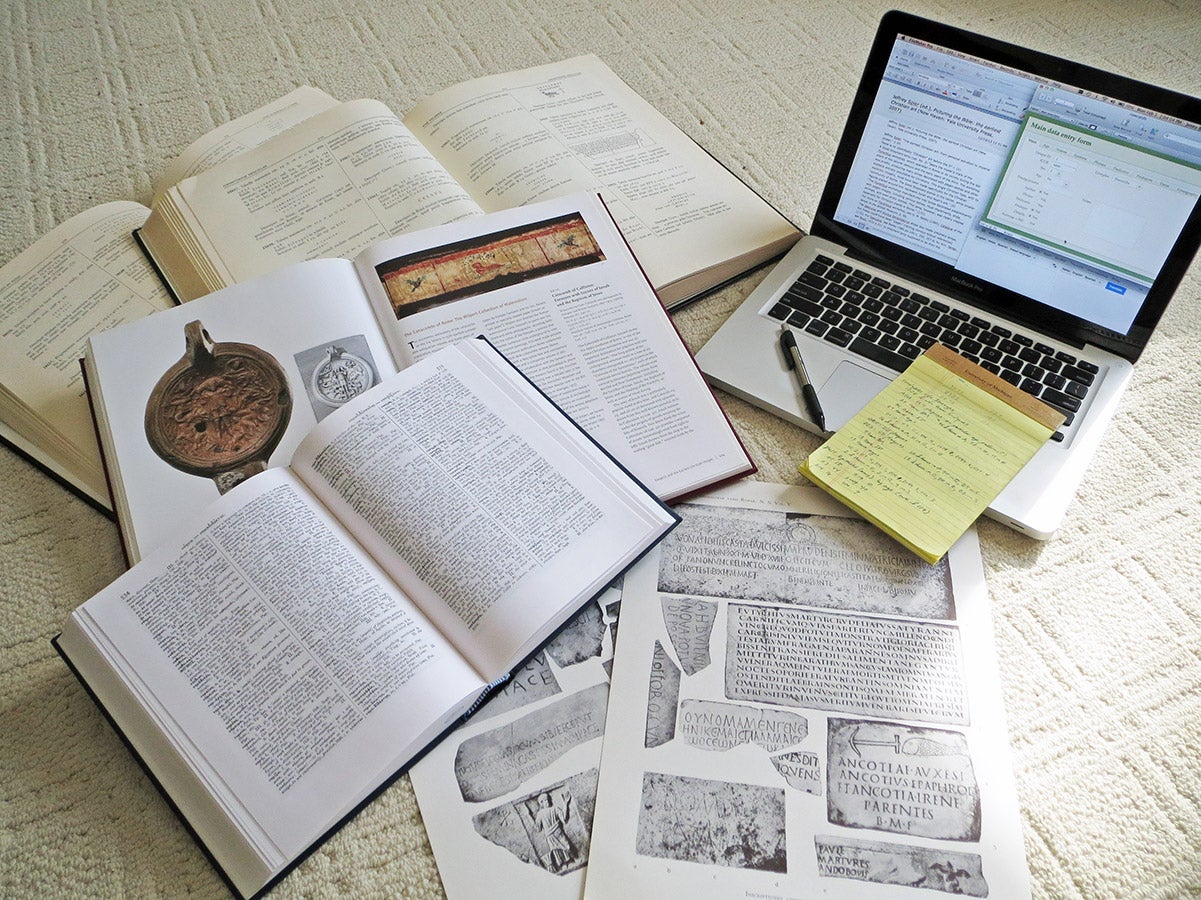

Enough with the background reading and procrastinating. This fall semester marked the official start of my dissertation, in written form at least. I feel like I’ve been working on this project for a decade already (although three years is more realistic). My dissertation is centered on my fieldwork at the Sant’Omobono Project in Rome. Specifically, I am interested in reconstructing the environment and topography of the archaic Forum Boarium. After returning from Rome at the end of the summer, I wrote a long to-do list of my intended accomplishments for the upcoming semester. A major part of that list was to write the opening chapters of my dissertation.

Although the primary goal was always hanging over my head, for weeks I couldn’t even begin to think about the dissertation. First there were conference abstracts that needed to be submitted, then countless grant proposals that needed to be dealt with if I had any hope of supporting my fieldwork in 2015, then just another book that I needed to read, then a meeting with my advisor, then some data crunching, then writing the conference papers … and so it goes. By the time the day came when I had nothing else to do, I just stared at my computer screen. An entire day wasted doing nothing but sitting in front of my computer! It is incredibly daunting to write the first sentence of such an intimidatingly long task. Upon lamenting (read: procrastinating) to my mom, she offered the true, albeit corny, words of encouragement above. I finally realized that I couldn’t avoid it any longer and started typing.

The main strategy that helped me get started on my first dissertation chapter was to write an extensive outline first. That way, I was able to get all of my thoughts on paper without having to worry about constructing vaguely coherent prose. This outline included the abundant references, which I would ultimately need to put into footnotes. After discussing the outline with the applicable committee member — and fortunately getting her approval — I was able to write more freely and quickly. I still encountered days where my momentum slowed, but I tried to keep the task in perspective. Each day was just focused on a particular section of a particular chapter. And each chapter isn’t so different from a seminar term paper, right? And I knocked those out tons of times as a pre-candidate, so why be intimidated by my dissertation? Well, that thought process worked for me at least. The semester is nearing an end and that long to-do list I wrote has been largely completed. Now, I just need to repeat the process next semester, and the semester after that, and the semester after that. But first, a break!

Writing a dissertation on the archaic Forum Boarium Read More »