“This Quintessence of Dust”: Micro-Debris Analysis at Olynthos

BY ELINA SALMINEN, PhD student, Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology, University of Michigan

This summer, the University of Michigan will be starting a new archaeological project at Olynthos in northern Greece in collaboration with the 16th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, the British School at Athens, and the University of Liverpool. The goal of the project is to excavate two 4th-century BCE houses and improve our understanding of ancient domestic spaces as well as northern Greek cities. In preparation for the summer, I traveled to Charlottesville, Virginia, to learn about micro-debris analysis, a technique we will be using at our excavation. It was a busy two days with Lynn Rainville, a micro-debris expert based at Sweetbriar College. We discussed the potential of the technique and devised a plan for how to apply it in the field.

In short, micro-debris consists of the small inclusions that are present in the dirt we excavate but are rarely noticed by the excavator. These inclusions can range from beads to small bones (especially from animals like rodents or fish) to very small fragments of pottery. Even though these finds seem mundane, they are worth studying for several reasons, especially in a domestic context. Imagine sweeping a compact dirt floor. What will be removed, and what will stay put? Research has shown that small fragments are more likely to remain where they fall, and can therefore give us a more accurate picture about the use of spaces when they were inhabited instead of after abandonment (which is when most of the bigger “finds” are deposited — archaeologists are often quite literally excavating through trash pits!). The technique can also allow us to see activities that might not otherwise be visible because they left little evidence, and to accurately compare the density of finds in different areas due to the careful counting and measuring involved.

The method itself can be quite tedious! After an excavator collects a soil sample for analysis of an area that seems interesting, the dirt is literally washed in a barrel to get rid of small grains of sand — in archaeological lingo this is known as flotation or wet-sieving.

In the process, botanical remains like burnt seeds will float to the surface and will be collected for analysis by specialists. The rest of the sample will be carefully picked through and searched for archaeological materials. The finds will then be sorted by type, counted, and weighed.

It is only after all this that analysis can begin.

Despite the slow and often boring sorting that is involved, it will hopefully be worthwhile in the end. We have come a long way from removing dirt by the cartful to expose monumental buildings with little regard to their contents and the people who used them. Using micro-debris analysis alongside multiple other methods, the project at Olynthos aims to study how different spaces were used in ancient houses, and even how these uses changed depending on the time of day or the season. Even though it might not look like much at first glance, micro-debris can help us get at the hustle and bustle of ancient houses behind the stone wall foundations that are visible to the visitor now.

“This Quintessence of Dust”: Micro-Debris Analysis at Olynthos Read More »

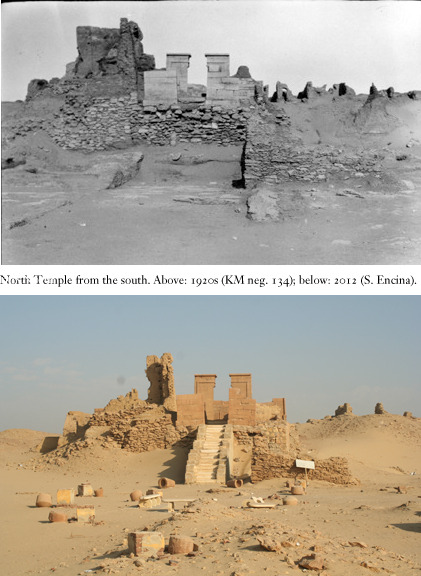

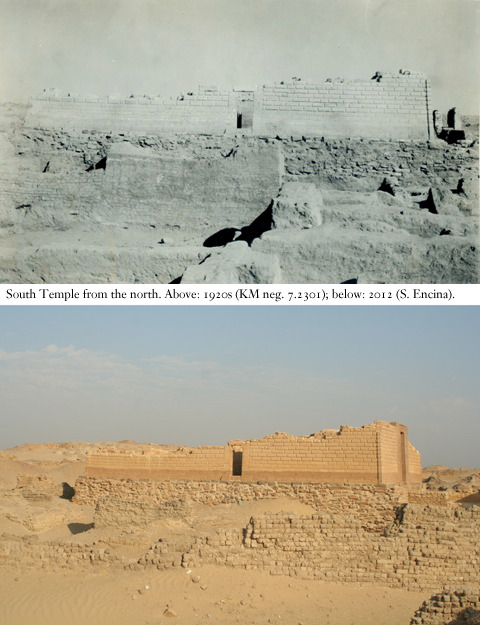

BY SEBASTIAN ENCINA, Collections Manager, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan

BY SEBASTIAN ENCINA, Collections Manager, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan