First season of the Olynthos Project

BY KATE LARSON, PhD candidate, U-M Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA)

In the past few decades, archaeologists have become more interested in the way people of ancient Greece actually lived. The evidence from written sources suggests that men and women were separated into different areas of the house, and they seldom discuss household tasks like cooking, weaving, and religious worship, which archaeology can illuminate. IPCAA professor Lisa Nevett has dedicated her career to understanding Greek houses, but until now she has had to rely on excavation data that focused primarily on architecture and intact artifacts. Nevett began to wonder how much more we might be able to learn about Greek houses if we used 21st-century archaeological techniques to pay attention to fragmentary material, non-fineware pottery, and microscopic chemical and organic materials preserved in soil. She, along with her co-directors Zosia Archibald of the University of Liverpool and Bettina Tsigarida of the 16th Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities in Greece, have been granted a five-year permit under the auspices of the British School at Athens to re-excavate one such site.

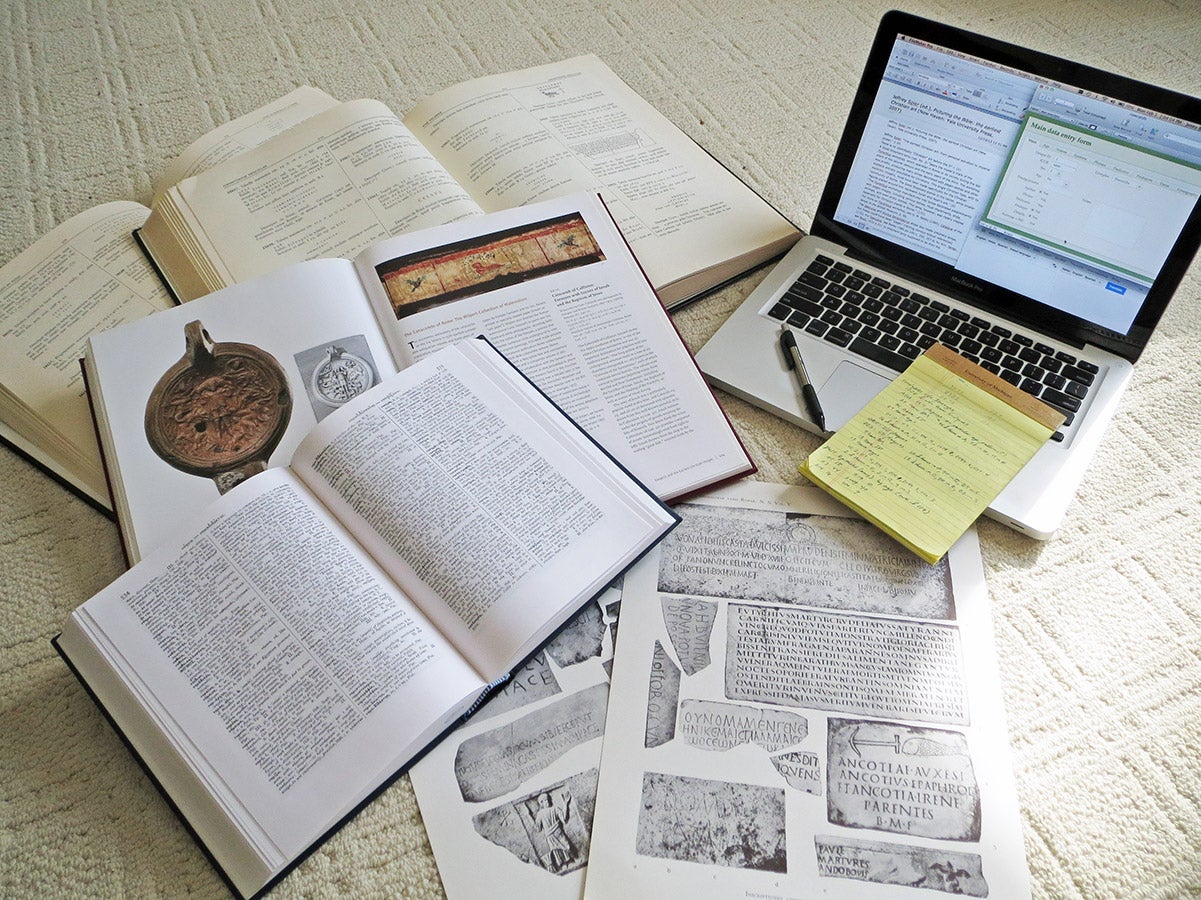

Located in the Chalcidice peninsula of northeastern Greece, Olynthos — no, that’s not a typo, although on a clear day you can see the famous Mount Olympus from the site of Olynthos — has been considered the “Pompeii of Classical Greece.” Historical accounts tell us that Phillip II of Macedon (the father of Alexander the Great) destroyed the city in 348 BCE and exiled all its occupants, who left behind their houses and belongings. The site was initially excavated by David Robinson of Johns Hopkins University between 1928 and 1938. Robinson found more than 100 houses, covering about 10 percent of the area of the site; each house contained a wealth of objects from daily life, including pottery, loom weights, figurines, and coins. While Robinson and his team carefully recorded which finds came from which rooms of the houses, the publications and archive don’t contain information about which finds the excavators deemed not important enough to record or save (such as fragmentary objects, non-fineware pottery, and bone) or any stratigraphic information about soil deposits and sequences. By contrast, the new Olynthos Project plans to excavate two houses over the course of five seasons using techniques not available to Robinson, such as geophysical survey, water floatation, micromorphology and microdebris analysis, geochemistry, and surface survey.

The project began in February 2014, when a small team conducted magnetometry and resistivity (types of remote sensing that help identify structures and features under the soil prior to excavation) in order to find promising areas for excavation. From July to August 2014, a multinational group composed of undergraduate and graduate students, professional archaeologists, and specialists in various archaeological disciplines came together to test these results and identify areas for subsequent work. Olynthos still has much to teach us about life in ancient Greek houses.

First season of the Olynthos Project Read More »