Inger Christensen’s book-length poem Alphabet — which follows the Fibonnaci sequence and covers ecology, nuclear violence, and love, among other things — contains what might be my favorite lines of poetry. Though I think about them often enough, I found myself thinking about Christensen’s lines frequently while reading Tom Sleigh’s The Land Between Two Rivers, recently published by Graywolf. Here they are, emphasis mine:

written otherwise only by children; and wheat,

wheat in wheatfields exists, the head-spinning

horizontal knowledge of wheatfields, half-lives,

famine, and honey;

I’ve always loved the phrase “head-spinning / horizontal knowledge” because it economically describes how confusing knowing contradictory things about the world can be. Such as what cardigan corgi puppies look like versus what nerve gas does to human bodies. Or half-lives, famine, and honey.

I thought about these lines while reading The Land Between Two Rivers because Sleigh’s prose — often about the ugliest things in life, war and rape and murder, and neglect for those suffering rape and murder — is beautiful and sensitive. His writing is simultaneously insightful, stuffed with facts, and beautiful at the line level, all without coming across as twee or overwritten. It’s really something.

I thought about these lines while reading The Land Between Two Rivers because Sleigh’s prose — often about the ugliest things in life, war and rape and murder, and neglect for those suffering rape and murder — is beautiful and sensitive. His writing is simultaneously insightful, stuffed with facts, and beautiful at the line level, all without coming across as twee or overwritten. It’s really something.

But I also thought about Christensen because Sleigh (a poet himself) weaves discussions of poetry into his essays about degradation, and the shift between topics can be “head-spinning.” Granted, some essays change gears more smoothly than others, but when the essays work they really work. The title essay, for example, is about Sleigh’s visit to Iraq with the University of Iowa’s Christopher Merrill, and deftly weaves together Sleigh’s impressions of Iraq with his experience teaching a series of creative writing workshops (an experience Sleigh also wrote about in his 2015 poetry collection Station Zed). It includes the following scene of “a slight young woman named Mariam” reading a poem to a Baghdad workshop:

Mariam stood very straight in front of her classmates and read to us with a quiet, unself-conscious dignity. Her pronunciation was excellent, so I have a good memory of what she wrote. She said that she was woken in her bedroom near dawn by her older brother, who had bent down to kiss her gently on the cheek, and to ask her if she wanted anything special in the market. And when she looked up at him, to tell him no, he said to her, very gently, that this would be the last time she’d be seeing him. But she was so sleepy, she didn’t quite take in what he meant, and a moment later he was gone. Later that morning, she wrote, she was in the kitchen having breakfast with her mother. And then their neighbor came in and gave them the news. She wrote that as she heard the news, she felt herself get smaller and disappear: she had no hands, no face, no body to feel with. There was no kitchen, no mother, no her. The neighbor, she wrote, told them about the “car accident.” She wrote how she remembers he brother’s words coming back to her, how gentle he was when he kissed her on the cheek, how he would always bring her special things from the market. And then she sat down, seeming completely self-possessed, except for the sadness that had come into her voice and hung now in the room. No one said anything for awhile, as what she hadn’t said — didn’t need to say, since everyone in her generation already understood — resonated for a few moments. Chris and I looked at each other, but we were slower in grasping what it was she’d left out. And then it dawned on us too: her brother had been a suicide bomber and blown himself up in the car.

While The Land Between Two Rivers is generally excellent, its parts do not form as cohesive a whole as one might like: where the first section’s essays are expressly about refugees and conflict, in the second section Sleigh moves on to World War I poetry (in “To Be Incarnational,” which uses his experiences in Somalia as a framing device for an analysis of David Jones and Wilfred Owen’s work) and imprisonment, Anna Ahkmatova, Gaddafi, and Tomas Tranströmer in “How to Make a Toilet-Paper-Roll Blowgun.” The collection’s third section contains four more personal essays, closing the book with “A Man of Care,” a lovely piece about Seamus Heaney, who addressed the Troubles in his work, and with whom Sleigh was close friends.

After the initial section of war/refugee essays, I found myself puzzled by the turns The Land Between Two Rivers was taking. Part of this may be because of the expectations I had going into the book — after all, its title is a reference to Mesopotamia, its subtitle is “Writing in an Age of Refugees,” and the book’s cover image includes a picture of a refugee camp. I was also somewhat disappointed because the initial section is so gripping, and what follows is a tad less gripping. The writing is uniformly fine, to be sure, but after scenes like the above from the title essay, and the following from “The Deeds,” who wouldn’t feel let down?

He paused again to sip his tea, then said in a quiet voice, “It was like a lake of blood and the deeds are stained with blood.” I assumed he was speaking in metaphors, until he asked, “Would you like to see the deeds?” He called his nephew on the cell phone. A few minutes later a heavyset young man of about twenty arrived on a motorbike to show me the deeds to the family’s property in what is now Israel. I could see that the paper was discolored with blood, the legalese obscured by three long, brown, faded stains. “The deeds were found by accident when my uncle and cousin came over to our house — after the soldiers dynamited it — to see if there was anything they could do to help us. I saw my home blown up. But the worst thing I saw, the worst thing I ever saw, was my brother, still a baby, suckling at my dead mother’s breast.”

Regardless of my griping about the collection’s curation, we need more books like this. The Land Between Two Rivers calls to mind James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in that both books were written by “amateurs” — both Sleigh and Agee are/were first and foremost literary writers, yet their books are works of journalism. This is a theme Sleigh revisits often: What is he, a poet, Sleigh wonders repeatedly, doing posing as a journalist in X desperate place? The good news for his readers is that Sleigh’s worries are unfounded, as his reporting is lively and intellectually engaging in a way that is too often missing from “traditional” journalism. We need more writing from poets like Sleigh, particularly writing about criminally underserved topics like the plight of refugees.

For example, according to the CIA World Factbook there are 1,467,670 refugees in Lebanon alone, a country smaller than Connecticut. Put another way, the number of refugees in Lebanon is a tick higher than the population of San Diego. Yet is this something we hear about? Does the fact that 1.5 million desperate people have been forced from their homes and crammed into a small, politically fragile country dominate the news? Instead, we are subjected to a steady stream of high crimes and misdemeanors, with the odd goofy flat earth story.

Of course, the media problem is well-known; it’s hard to get people to care about things that don’t affect their lives. But what’s striking is the degree to which experts also don’t know what to do with refugees. For example, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study — which reports on and analyzes “health loss from hundreds of diseases, injuries, and risk factors” — aggregates data by region and country, covering 195 countries; there are few gaps in GBD’s coverage. But if GBD reports population health by country, how are refugees, who don’t have countries, counted?

To wit: one can find primary sources related to refugee health in the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx, which houses GBD data), but there is a dearth of refugee-related data sources in the otherwise data-rich GHDx. If one searches for “refugee,” in the GHDx, one finds sixty-seven sources. If one searches for “North Korea” — and the Hermit Kingdom isn’t exactly a fount of information — one finds 12,579 sources. Additionally, the only mention of refugees in the main GBD 2015 paper about Middle Eastern health, “Danger ahead: The burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990-2015,” comes in the following terse statement:

The wars and unrest have led to major migration and a large refugee population inside and outside the region. For many host countries, the existing health systems and infrastructure do not support such a large additional population.

I could go on and on; the point is that The Land Between Two Rivers is important and necessary (in addition to being very, very good). And finally, it’s also does one of best things literature can do, which is inspire interest in literature. It made me want to read other work by Sleigh, discover other writing like this, and finally, spread the word about this book.

Finally, because Sleigh is a poet, and because one of the major themes of The Land Between Two Rivers is using literature as a lens through which the world can be examined, I’d like to end with a poem. This is from Station Zed’s “Eclipse”:

A nail in the wall is what the world hangs on:

a poster of the latest “big man” whose name

in fifty years nobody will know; or Jesus looking

put upon, head drooping on the cross, hands bleeding

a hundred times over in the wooden gallery

of tiny Jesuses for sale. Or else a mosquito net

drapes down in a gauzy canopy

over the narrow, self-denying cot

where you sleep for a few hours, sweating out

malaria between parsing words

writing the fatal formula that cuts

into the mind terms you can’t live with or without:

“We are foreign men in a white world,

or foreign-educated men in a black world.”

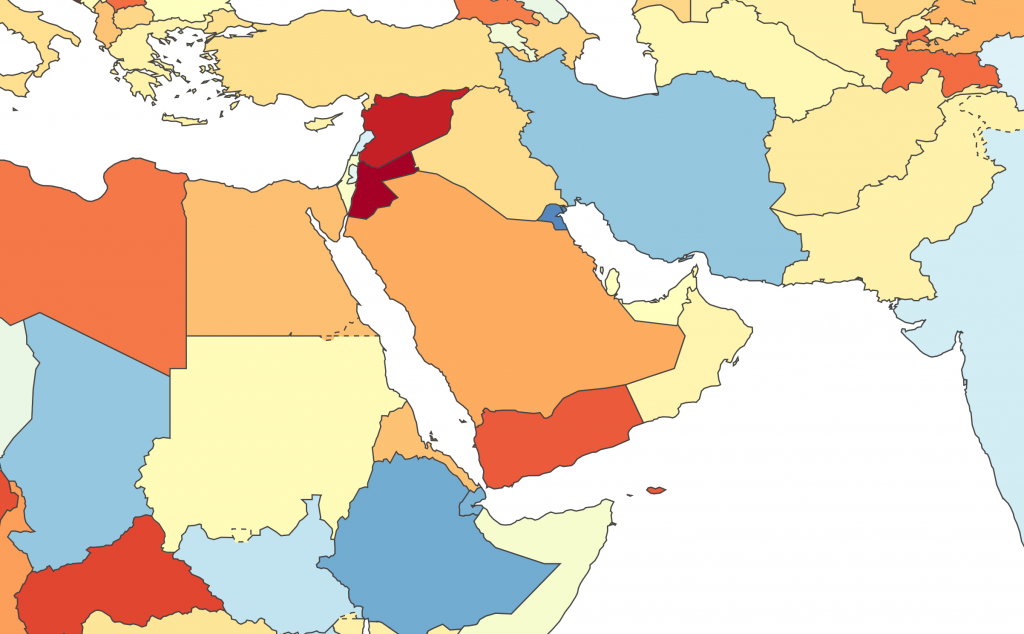

Top image courtesy of the data visualization tool GBD Compare. It shows the annual rate of change in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) — one DALY equals one lost year of healthy life — caused by “forces of nature, conflict, and terrorism, and police conflict” per 100,000, both sexes, between 1990 and 2016.