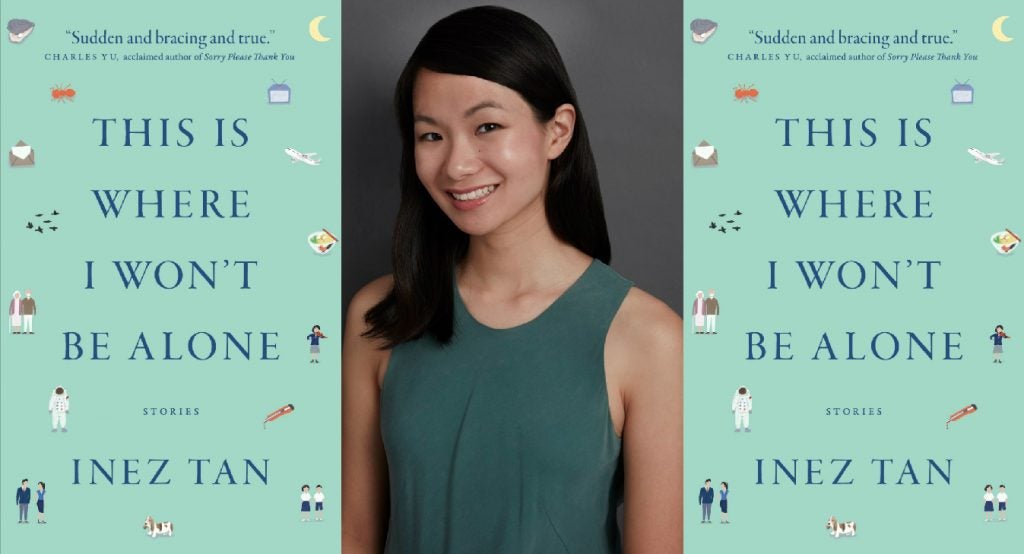

Can coming home ever be simple? That’s what Inez Tan asks in her debut story collection, This Is Where I Won’t Be Alone (Epigram Books, 2018). Over the course of thirteen stories, Tan unpacks the ways intimacy with a place, person, or idea can be at once comforting and alienating. Tan spent the majority of her childhood in Singapore, and while most of the stories take place there, the settings range from an American college town to a magical kingdom infested by dragons to a colony on the moon. By turns hilarious and devastating, but always surprising, Tan’s stories stick in the reader’s mind long after the book has been closed.

This Is Where I Won’t Be Alone is a collection that reels the reader in and refuses to let go. Inez spoke with MQR via email; the conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Your book has been a runaway success in Singapore, debuting at #4 on the Straits Times bestseller list before climbing to #2. So first off, congratulations! What’s it like to beat out Kevin Kwan and Dan Brown on the bestseller list?

Thank you! I’ve just very grateful that there are people out there reading the book! And hopefully, the rankings mean that more people will get to hear about it.

Thank you! I’ve just very grateful that there are people out there reading the book! And hopefully, the rankings mean that more people will get to hear about it.

All of these stories are, in one way or another, about home, and the nuances of what it means to call a place home. As a writer, what does it mean to write about home, and more generally, about place? What do you draw on when you’re thinking about portraying place?

During my MFA at the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan, I was reading a number of collections that revolved around place, like books by Karen Russell (Florida), Claire Vaye Watkins (Nevada), Rebecca Lee (New York City), and Amy Hempel (Southern California). I thought I’d try to put together a collection set in Singapore, where I lived from ages seven to fifteen. I wanted a title that most people from Singapore would recognize. That led me to a beloved National Day song, “Home” by Kit Chan (apologies for the quality, and the wardrobe — this was 1998), and a line from the chorus: “This is where I won’t be alone, for this is where I know it’s home.”

I’d grown up singing this song, but only then discovered how melancholy it is. It begins, “Whenever I am feeling low, I look around me and I know — there’s a place that will stay within me, wherever I may choose to go.” It’s a song about leaving and traveling and not always knowing where home is, which I began to realize was a familiar experience to many people in my generation. That was my way into writing about Singapore, and still is my relationship to it.

I heard somewhere that your themes are what you can’t help returning to, what you write about even when you’re not aware of it. That was what happened for me with this book. After I had the title, I went back to some stories I’d written earlier, and I realized that they fit — even though one took place entirely in the US, and another was about a princess and a dragon — because they were also about home and belonging. I’d written a story set on the moon, and setting aside the astronauts and the generators powered by dogs on treadmills, it was all about missing people who were far away, or felt far away. (Also, I love the moon. Like math, it’s the same in every country.)

As for portraying place, I’ve spent the last ten summers in Singapore, but I wrote most of the stories set there while I was living somewhere else — Williamstown, MA, Ann Arbor, MI and Southern California. I was relying on what I could remember. But Singapore changes so quickly that a lot of our poems and stories, for better or for worse, are about parts of it that don’t exist anymore, except in people’s recollections. One of my stories is set in the McDonald’s that used to be at King Albert Park. It was well-known to all the nearby schools, the place you went to study in air-conditioning and meet boys/girls. That all made perfect sense to me, but as I wrote the story I realized how strange it was, at the same time, to someone looking in from the outside, this American fast food chain that was also such a part of growing up in that part of Singapore. That story (incidentally titled “Home”) is the one that allowed for the most direct thinking about the questions I’ll probably spend my whole life answering: “Where does a sense of belonging come from? A place? Who you were there, and who you were with?”

You mentioned that you wrote all of these stories when you were living away from Singapore, and that you relied mainly on memory. Did that distance help you? Do you think we need to be away from home to write about it?

The distance did help. So did having the constraint of memory, once I started viewing that as something I could work with. For example, in “The Colony,” the main character is a man named Boon who’s lost his job, and with it, his sense of self. I placed him in a suburban neighborhood that I remembered from visiting a friend who lived there more than ten years ago. Midway through the story, I realized that Boon needed to go to Popular Bookstore, a well-known chain that mostly sells stationery and textbooks (more like Staples than Barnes & Noble). The problem was that the branch I knew best was pretty far from Boon’s neighborhood — it didn’t make sense for him to go there. If I’d have been living in Singapore, I think I might have been tempted to find and visit a branch closer to where Boon lived, in an attempt to be as authentic as possible. But sitting in my apartment in Michigan, I realized instead that I could make what I knew work for the story. The whole point was that Boon, being unemployed, has too much time on his hands — why shouldn’t he go halfway across town to buy two things?

I don’t believe that fiction writers should only write from personal experience, but there are probably limits to how far we can go beyond it. That’s what Flannery O’Connor meant when she wrote that that the imagination “is not free, but bound.” More recently, I read Liu Cixin’s afterword to The Three Body Problem in which he described how his particular background led him to write science fiction, and I thought his imagery was amazing: “Every era puts invisible shackles on those who have lived through it, and I can only dance in my chains.”

I couldn’t generalize about whether all writers need to be away from home to write about it, but living between places definitely keeps me observant.

You were talking a bit about themes, too, specifically themes of home and belonging, of which there are a lot in the collection. But you also noted that the National Day song you were inspired by is quite sad (as an aside, I’ve noticed this about the lyrics to a lot of pop songs). In addition to themes of home and belonging, I feel like a lot of the stories in This Is Where I Won’t Be Alone center around loneliness or melancholy. Can you talk a little bit about that thematic tension? How do you go about balancing the many ways we can feel about the places we’re from?

I hadn’t quite realized this before, but I think I try to include thematic tension in everything I write. Jim Shepard was my thesis adviser at Williams, and he used to draw these faint little diagrams in pencil on my stories. They looked like molecules — like there’d be a bubble with “loneliness” connected by a line to a bubble that said “family,” or “intimacy” connected to “fear” and “avoidance.” I always felt reassured when he drew those diagrams, because it meant he could see a story coalescing. Jim also identified really early on that a lot of my characters teeter between closeness and isolation (probably when I brought him “Talking to Strangers,” which is the oldest story in the collection). Thanks, Jim!

There’s an inherent tension in the title of the book. To me, this is where I won’t be alone sounds resolute and insecure at the same time. There have also been a lot of times in my life that I’ve really wanted to be alone — but during the eight years I was working on this book, I was also realizing you can’t just opt out of your communities, your family, your country, and so on — they’re a part of you, and you’re a part of them. So that’s something many of these characters realize too, whether they’re fighting with their mom over the phone or teaching social studies to middle school girls in a slightly science fictional 2039.

I hope the characters in the collection navigate the places they’re from in a variety of ways. Curie in “Edison and Curie” finds her place in society (quite literally) when she realizes she’s a caregiver at heart, even though that means accepting that her work will never be seen as prestigious (i.e. worthwhile). After Boon in “The Colony” loses his job and is no longer productive, he struggles with feeling like he belongs. As for me, in some ways I’ve gotten more conflicted I feel about the places I’m from, not less. I wonder all the time if it’s even possible to say I’m from more than one place, more than one culture. (I think it is, but I do wonder.) I think when you try to love something more, when you try to know it better, you have to see it more clearly, with all its beauty and its pain.

Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche communities for people with disabilities to live together with those who assist them, completely changed my thinking on community. He writes that it’s a place of pain, the death of ego, where we forgive those who are different from us and are forgiven, and that’s the only way we grow. I don’t think I’m saying that home just means accepting pain — I think it means you keep moving closer, through the times you want to pull away.

I love realizing that the lyrics to a pop song are actually devastating. This is a silly example, but one time I was in a car with friends singing along to that techno remix of Lana del Rey’s “Summertime Sadness” and I realized that everyone else thought that the words were, “I love that summertime, summertime, summertime.” Totally different song.

You just referenced two of my favorite stories in the collection: “Lee Kuan Yew Is Not Always the Answer” and “Oyster.” Let’s start with “Lee Kuan Yew.” That story takes place in the not too distant future, and one of its major concerns is the way characters memorialize Lee Kuan Yu, who was essentially Singapore’s founding father. This question is a two parter: First, can you talk a little bit about your relationship to Lee Kuan Yu’s legacy? How did that come through in the story, if at all?

I once heard poet Ross Gay says something like, “I know a poem is done when it’s done something in me.” Sometimes we need to grow, or change, or discover something we didn’t know we knew in order to write a particular piece. “Lee Kuan Yew is Not Always the Answer” was one of those stories for me. It had everything to do with processing my relationship to Lee Kuan Yu’s legacy and the ways Singapore’s history intersected with my own, though that only became clear to me after I finished writing it.

Basically, that story has two acts. In the first, Cheryl, a middle school social studies teacher, discovers that her students have a running joke: that Lee Kuan Yew is always the answer, because he was responsible for so much of Singapore’s history. So they’ve been writing down Lee Kuan Yew’s name as the answer to every exam question they don’t know the answer to (“The process by which a solid turns into a gas is called Lee Kuan Yew”). The second part of the story is what Cheryl does about it. Figuring out what that was was what the story had to do in me. I didn’t go, “I’ve figured out my relationship to Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy, so now I’m going to write fiction about it.” For most of the writers I know, writing fiction is how we figure out what we think. That’s our way of being in the world.

But I’ll try to actually answer your question directly! Cheryl was born the day Lee Kuan Yew died. (It was a little surreal to revise the story to include the exact date, after it happened: March 23, 2015.) I was born in 1990, the year he stepped down as Prime Minister. He immediately took up the post of Senior Minister, and remained active in the government for many more years, but his biggest achievements were far enough in the past that I was learning about them as history in school.

Both Cheryl and I have the sense that the world we live in was completely shaped by his legacy, in good ways and bad, materially and intangibly. To give one quick example, my grandparents, who were roughly from Lee Kuan Yew’s generation, never finished grade school (that was also during the Japanese Occupation during WWII). As the country developed under Lee Kuan Yew’s government, my parents learned English in school, earned graduate degrees, and worked overseas. So did I. By that measure, we’ve accomplished a lot in a very short time.

But that kind of progress comes with its own baggage. Like ruthlessness — Cheryl’s mother, who would have been my contemporary, points out that Lee Kuan Yew advocated for less-educated women to have fewer or no babies; he thought that would hamper national progress. What she doesn’t say directly is that she’s a single mother — her daughter would have been frowned upon as well. At the same time, and arguably as a result of having absorbed that kind of national narrative of progress, Cheryl’s mother has oppressively high expectations for her daughter to achieve more than she did; she’s bitterly disappointed when Cheryl doesn’t get into Oxbridge and goes to the local teacher training college instead. Cheryl’s mother is passive-aggressive, unpleasant, and loving all at the same time. As a result, Cheryl has a humorous exterior, but a hard-headed, deeply pragmatic core that I hope is a little heartbreaking by the end.

I’d say that both Cheryl and her mother have qualities that I see in myself and people I know that we could attribute to Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy — but we could never trace who we are just back to one single person. We’re all interconnected. That’s the conclusion Cheryl’s mom comes to: “Lee Kuan Yew did a lot of good … But so did every person who worked hard to make a better life for their family and themselves. Every single person.

Second part: That story also stands out to me in part because, shortly after you workshopped it at Michigan, the real Lee Kuan Yu passed away. What was it like to see something you’d written come to pass?

This will sound blunt, but I knew I was writing about something that was going to happen, and on some level, I’m sure I was writing that story to help myself prepare for it. On a lighter note, it was just fun writing in sci-fi elements like the flying food service robots, and figuring out why middle school girls would still need to take Social Studies in a future where they could just get bionic feeds implanted in their heads (spoiler: because your brain hasn’t stabilized enough before you’re twenty-one). I’ve always loved how science fiction set in the future allows you to work out the implications of something that’s happening in the present, like George Orwell writing 1984 in and about the year 1948.

“Oyster” is told from the perspective of a dried oyster, which is amazingly strange point of view choice. I’ve literally never read a story like it. “Oyster” strikes this perfect balance between humor and sadness, and so much of that is due to this totally unique narrative strategy. What inspired that story and that choice of narrator?

I’m sorry to say that “Oyster” is based on a true story. My mom gave me a bag of dried oysters to take back to Michigan, and they went moldy in my fridge because I was too lazy to cook them. It was excruciating to take the symbol of my mother’s love and throw it in the garbage. But kind of hilarious at the same time.

That story didn’t become funny and fresh (sorry not sorry for the pun) until I rewrote it from an oyster’s point of view. When I did, I found plenty of unexpected parallels between the oyster and the daughter — they both go on transatlantic journeys, for example. More importantly, it gave me more to work with for the ending. I always knew the story would end with the daughter putting the oysters in the trash, but writing to find out how the oyster would narrate the experience kept the story alive with possibility in ways that the limits of my own personal experience didn’t.

I had no idea you’d initially approached “Oyster” from the daughter’s perspective. It’s amazing how much a story can shift when you change the narrator. This next question is also kind of about narrative approach: In addition to being a prose writer, you’re also a poet. Did you find that concentrating on poetry during your second MFA changed or inflected the way you wrote fiction? And if so, in what ways?

Absolutely. Focusing on poetry for a while made me want more from my language. I basically wrote all the stories in the book, then wrote poems for two years, and when I returned to do final edits on the stories, I was amazed at how many sentences that had seemed fine now felt insufficient.

One sentence I was working on right to the very end was the last line of “Edison and Curie.” Throughout the story, the twins Edison and Curie and their younger sister Elise have been rivals, forced to compete against one another, but in the last scene they’re finally just together, drawing. Elise is drawing rectangles, Edison is drawing squares in her rectangles, and Curie is drawing circles in his squares — a very simple scene of people in city blocks. For years, the last line was “They spent the rest of the afternoon together on their knees, creating visions of a city together.” But after reading and writing a lot of poetry, that sentence didn’t seem precise enough. So I tried a lot of different descriptions: visions of a simpler city, visions of a happier city, and so on.

Finally, I realized that what these characters wanted was to belong in a place where they wouldn’t be valued differently based on their achievements. What they were envisioning was a more equal city together.

Sometimes in fiction, I think we worry about writing flowery prose, so we default to dullness instead — language that isn’t sharp or shiny. But poetry (at least the kind I’m drawn to) is all about boldly taking risks with language, especially when it comes to the big subjects like death and love, or the really big things we feel and believe. So now I think, if you’re not going all out in your own writing, what are you waiting for? Before, I had written some cornfields into “On the Moon.” Just, “cornfields.” I thought stories were supposed to have boring, realist, unremarkable cornfields. Post-poetry, I described them as susurrant cornfields. A minor moment, but I counted it as a major victory. Those are much better cornfields now.

When I teach, my analogy is that fiction is a huge tree while poetry is a bonsai. It’s immensely helpful to toggle between working on different scales. Fiction helps me infuse my poems with narrative. Poetry makes my fiction more deft, descriptive, and concise.

Which was your favorite story to write and why?

My favorite moments are the funny ones. Those were the places I most felt I was getting something right about the characters and their worlds. Humor doesn’t stick if it’s not getting at something true. I’m realizing that what I consider the funniest moments are all instances of ridicule, and those occur at the highest rate in “Edison and Curie,” where there was so much from my own experience of going to school in Singapore that I wanted to make fun of. Like kids who think they’re being really smart when they say things like, “I’m so talented that I feel cursed. Sometimes I wish I were more normal.” Or, “Is baby-flavored ice cream abhorrent if it contains no real babies?” At the same time, I hope the humor isn’t just there to be snarky. I want it to be in service of seeing its objects more clearly.

“Edison and Curie” was the hardest story to write, but very satisfying to get right. In its earliest stages, it was heavily modeled off “The Remission” by Mavis Gallant. I love that story, but its ending feels a little mean — like we’re ultimately mocking the characters for turning into their worst selves. Originally, “Edison and Curie” was just about Curie becoming an utter failure — after flunking all her exams, she tried to commit suicide, but she couldn’t do that right either. That was closer to Gallant’s arc, but eventually I realized that wasn’t the story I wanted to tell. It took me years, but I’m really happy with the way it ends now with Curie finding her rightful place, yet still having mixed feelings about it. Despite everything she goes through, she still has her sense of humor at the end. That makes me glad.

I ask everybody this question, which is drawn from a creative writing exercise at the high school where I used to work (I didn’t actually write the original prompt, so I can’t take credit for this question, I just like it): Pick a character from your favorite story in the collection. What is their favorite song? What’s a song they love but would never admit to loving?

Oooh, great prompt! One great and weird thing I love about Singapore radio is it still plays 90s/early 2000s pop all the time. When I walk into a supermarket or a 7-Eleven, I kind of expect to hear the Backstreet Boys. I think Curie would be really into “Shape of My Heart.” I think she’d be okay with admitting it by the end of the story. Looking back on the things she’s done, she was trying to be someone, she played her part, kept you in the dark, but now let her show you the shape of her heart.

Find out more at ineztan.com.