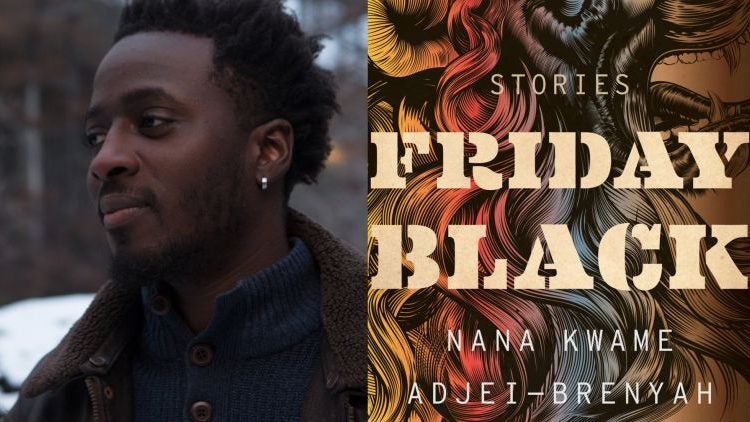

When I Skype-called Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, debut author of Friday Black, we talked about family. We began with the families in his collection, from the father whose writer son drives him into the mystic-bureaucratic maze of “The Hosptial Where,” to the mother who, when the TV goes dark from loss of electricity, says, “Good. Now you can read more.” Naturally, the conversation led to our own families, the Ghanaian parents who had to relearn life in America, who love us but with whom there are always gaps, barriers of experience. These are the parents who populate the stark worlds of Friday Black, who witness their children struck down and try to prepare the living to face a world not made for them. Family, Adjei-Brenyah said, is “one of the hearts” of the book, which he dedicates to his mother, who asks: “How can you be bored? How many books have you written?”

Indeed, the second story “Things My Mother Said” embodies the tough love humor and resilience of this maternal voice. The narrator of this brief memoir-like ode writes of his mother: “She’d often say, ‘You are my firstborn son, my only son,’ as a reminder not to die.” And death, which is often not a choice in a book that is so close to our world, breathes on every page, because death walks hand-in-hand with blackness in America.

In “The Finkelstein 5,” the gripping opening story that sets the tone for the familiar universes Adjei-Brenyah unfurls and questions, Emmanuel Gyan wakes up from a dream in which “Fela, the headless girl,” waits for him to do “something, anything.” But hold that breath of relief because this dream is not a dream Emmanuel Gyan can wash away with the morning. He is not afforded the comfort of dreaming. He is black. He must dial down his blackness on a 10-point scale if he wants a chance at life. At the beginning of his day, Emmanuel is grateful for a job interview with Stich’s, “a store self-described as an ‘innovator with a classic sensibility’ that specialized in vintage sweaters,” but feels guilty of his luck while his community is in mourning. So he wears loose-fitting cargoes, a black hoddie, and a snapback cap, dialing up his blackness to more dangerous levels in an attempt at solidarity. Later, his father says he is proud regardless of the outcome and reminds Emmanuel to “wear a tie and try to speak slowly.” With every slight thought, Emmanuel negotiates with his blackness and himself, careful about what he wears and how he wears it, what he says and how he says it.

“The Era,” a remarkable voice-driven story set in a futuristic world, follows Ben, a fifteen-year-old, who lives in a future where perfection can be engineered, where the non-perfect are ridiculed and emotion is discouraged. Here, positive feelings are delivered in a daily dose of “Good,” and Ben yearns for more and more “Good.” It is a world in denial of the war-torn past and the war-torn present, a world we know but only acknowledge when we must.

In these pages, you will find the Westworld-reminiscent theme park in “Zimmer Land,” where people pay to shoot black bodies in the “safety” of simulations. In “Lark Street,” a young college-prospect father cannot escape his unborn children, who materialize and confront him. From the retail zombie-rush of the titular (and familiar) “Friday Black,” to the infinite loops of an apocalyptic world in “Through the Flash,” Adjei-Brenyah introduces us to characters trapped in systemic claustrophobia, everyday people who go to work and provide for their families and dream of another life, a life where flight is possible.

“Through every struggle, you want to know who cares about you,” Adjei-Brenyah told me, “who loves you.”

Ama Grace Knife Queen Adusei, a fourteen-year-old terror who turns a new leaf at the beginning of “Through the Flash,” repeats her days after a bomb is dropped on them. Ama loves her brother Ike most of all, but she wants her mother, whose name her father calls every time he kills Ama. “There are no more real kids,” she says. “Even the babies know they’re stuck.”

“We aren’t gonna be people,” Jackie Gunner and Jamie Lou tell their father, whose mantra is, “It wasn’t my fault.”

“I don’t know what to do!” screams Emmanuel, echoing the voices on our streets locked in loops of violence and injustice.

In these stories, Nana Adjei-Brenyah demands we not look away.

There is an unnamed character in this book, an observer that feels like the main character of every story, who haunts these pages. He hovers above you as you read and if you listen close, you might hear him say:

Look at everyone around me. Look at the world we’ve made. I am a window. I am trying to remind you to pay attention. Do you see yourself? Do you frighten yourself? Don’t close your eyes. Stay here, in this mercy you are afforded.

Somewhere in the nearby universe of my Google Docs archives, there is a version of this essay that mentions how my brother, who is named Friday, introduced me to anime and taught me how to stay a child a little while longer. This is the version in which I attempt to run away from my own confrontation of the real. After my questions led Nana Adjei-Brenyah to share that he too watches anime with his siblings, I asked if the hole in Fuckton’s chest (“Light Spitter”) was a nod to hollows, the soul-consuming monsters in the shonen anime Bleach. Our conversation was light, sprinkled with chuckles. I did not want to veer into the dark and the heavy. I wanted to draw pictures of enduring families, without the ghosts and the scars, an unreality, an escape. But that version would be a lie, an injustice to the work Adjei-Brenyah does in this book. Yes, these stories are hard to read. They are hard to consume in how present they are, how unflinching. And they are true.

Under a sky that rains pain and violence in a never-ending loop, Ama says:

Even the apocalypse isn’t the end. That, you could only know when you’re standing before the light so bright it obliterates you. And if you are alone, posed like a dancer, when it comes, you feel silly and scared. And if you are with your family, or anyone at all, when it comes, you feel silly and scared, but at least not alone.

This is how Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah writes about family. This is how he confronts reality.