Lena Mahmoud’s Amreekiya is a novel told from the perspective of Isra Shadi, a young woman of mixed Arab descent, during both her marriage and childhood. As a girl, Isra endures the loss of both her parents, one to illness and the other to addiction, and must find a place for herself within her uncle’s often unwelcoming family; as a woman, she marries Yusef, and the two struggle to make their union work in the face of family pressure, a miscarriage, and two stillborn children. With this dual narrative, Mahmoud explores the impact of culture and gender on our everyday lives. Library Journal’s starred review describes Amreekiya as “relevant for people worldwide,” and Foreword named it as one of 2018’s “Four Phenomenal Debut Novels.” Mahmoud, who is of Palestinian and European descent and grew up in California’s Central Valley, has previously published her work in Fifth Wednesday, Sukoon, The Offing, and A Gathering Together, among others; she has received two Pushcart nominations for both her short fiction and creative nonfiction.

In an email interview, Lena Mahmoud and Dr. El-Gendy discussed the power and importance of mixed or hyphenated identities in Amreekiya, the growth and transformation of contemporary Arab American literature, and the confluences between cultures and genders in both life and literature.

Nancy El Gendy: The topic of hyphenated identities is central in Amreekiya. It is also a dominant one in third-wave Arab American literature. Why is this subject important to you? Do you agree that Arab-American writing comes in three waves?

Lena Mahmoud: I studied Arab American literature, especially Arab American women’s literature, in my undergraduate and graduate English programs. I used that framework when I wrote my master’s thesis on Arab-American women writers in 2014, but I do think we are beginning to see a new wave emerge–those that deal with the most marginalized in the Arab American communities: people who don’t come from traditional families, queer Arabs, and black Arabs. I do believe that the discussion of hyphenated identities is important, and, whether it is acknowledged or not, most people have multiple influences that impact who they are. I think that is why labels often feel so incomplete: we expect too much of them. There’s no way that a person’s identity can ever be effectively whittled down to just a few words.

NEG: The variety of dress codes helps shatter, or at least question, dominant Western stereotypes against Arab and Muslim women as a one homogenous group. Amreekiya’s depiction of hijab is clever, but I wonder how Islamophobic and Islamist readers may interpret it. Any thoughts on that?

LM: I believe that we all sometimes have contradictory feelings and beliefs like Imm Yusef, and Isra finds this amusing because of how rigidly Imm Yusef claims modesty as a virtue. As for any Islamists or Islamophobes, I highly doubt either group would be interested in Amreekiya because of who Isra is (an ethnically mixed woman who does not wear hijab), but, as a narrator, Isra does not espouse a strong stance for or against the hijab. Also, she kind of derides both Amtu Samia and Imm Yusef’s view on hijab: Amtu’s view is classist and Eurocentric, and Imm Yusef’s is sexist. Ultimately, though, I was more concerned about showing the various influences and pressures in Isra’s life, which include wearing hijab, rather than educating people about hijab. I trust that my readers are intelligent enough to understand that the statements and beliefs of my characters, including Isra, are subjective and not meant to make a statement about a personal and religious choice like wearing the hijab.

NEG: During the family trip to Palestine, “Falasteen,” Isra’s uncle, Amu is embarrassed by “how little [she] knew Arabic and Islam” (50). To him, language and religion are values to brag to show off. Any further thoughts on that?

LM: Yes, Amu Nasser is concerned about appearances, and this is partly because he is shallow and fickle, but it’s also because pride in his religion and culture would cost him much more than it would for someone from a dominant culture. Imagine if he went to work wearing a kaffiyeh or had a sign in his law office that said “Free Palestine”? So it’s self preservation as well, and he extends that to his children and Isra as well. However, when he returns to Palestine or is around other Arabs, he feels ashamed about how much he and his family have assimilated. Unfortunately, most societies do not make it easy for those who are in between. So, in a less obvious way, Amu is in a similar situation as Isra in terms of feeling forced to choose among the cultural influences in his life.

NEG: Amreekiya critiques several ideologies and institutions, including anti-Arab racism, patriarchy, sexism, U.S. cops and schools. Do you see Amreekiya as a counter narrative?

LM: When I was writing Amreekiya I didn’t think of it as a counternarrative or an expose, but in the course of writing Isra’s experiences, it just came naturally that Isra would encounter both anti-Arab racism as well as racism within the Arab and Arab American community in addition to the intense presence of the sexism that comes with patriarchal societies (both Palestinian and American) that Isra lives in. I actually don’t think that I took schools and cops to task hard enough because it was not essential to the story. In my view these ideologies and institutions affect our everyday lives but often we only discuss them in abstract ways, and that keeps us from feeling compelled to do anything about them.

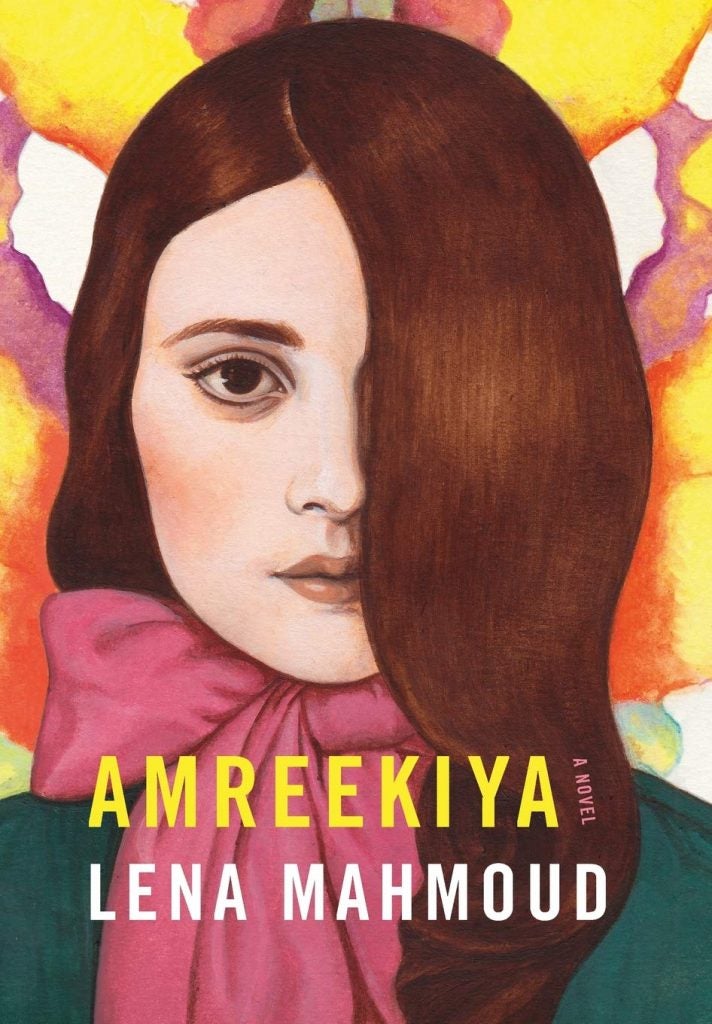

NEG: I loved the cover of the novel: long hair covering part of a woman’s face in front of a watercolor background. What’s the story behind this intriguing cover?

LM: I had a really positive experience with the cover. This was actually the first one that the University Press of Kentucky sent me, and the cover represented Isra’s personality well. She is a secretive person but also telling the reader her story frankly and openly, so it makes sense for her to be partially hidden but looking directly ahead at the viewer. I have to admit that when I was first in the process of signing the book contract for Amreekiya I was a little concerned about what the cover would look like just because I saw that so much of Arab American women’s writing has been badly represented by book covers that reinforce stereotypes.