(translated from the Bulgarian by Dimiter Kenarov)

I don’t know of anything else in our history that has caused more pain and suffering than that deranged spark, in the eyes of some members of the human race, called patriotism. On the face of it, it seems impossible to explain how normal, rational people all of a sudden lose their sense of reality, their reason, their good humor and self- awareness, to become prey to a genuine psycho-pathological condition, which denies the natural link to other human beings and replaces it with the mentality of the pack.

Our neighborhood, our village, our town, our state, our history, our beaches, our apples, our army… are mightier, prettier, tastier, richer, more meaningful, more special, more courageous than those of the rest of the world.

Without making a distinction between patriotism and chauvinism, in their contemporary context, I view both as the tragicomic hostility of the small “private” world to the wider “factual” one. From a psychological perspective,this may be the result of an inner necessity to ascribe to ourselves, and to our own place in the world, greater meaning, to seek out sources of self-esteem and fulfillment and to discover them in arbitrary rivalries. After all, a great many people on this planet feel happy only when they know that there are others who are less so, and vice versa.

We usually say that patriotism is nothing more than love of one’s country, language, history, and nature. And I agree that there is nothing wrong with loving the language you speak, the country you live in, the house where you were born; to respect your ancestors and their history. Of course – and let me make this point clear straight away– neither is there anything wrong with the exact opposite of this, i.e. not loving your country, or your ancestors, or your history, or your language, for we are all subject to different experiences. But we cannot and should not equate natural attachment to and love of country with patriotism. Those feelings are deeply private and intimate; they are part of the so-called spiritual sphere, while patriotism is a phenomenon which belongs on city squares.

In any case, patriotism has always been an expression of an inferiority complex, a nation-wide inferiority complex, and perhaps here lies its social power. Patriots usually form the most united, sturdy, determined, mindless packs, easily swayed by ambitious leaders and shrewd politicians. And that is why patriotism is that fierce, barbaric force, which has been most responsible for pitting one people against another, alienating us from each other. Patriotism is perhaps the strongest opium of the masses, the most inebriating and inspiring one, and quite often we see wise and sober individuals falling victims to it, as patriotic speech affects the instincts, the most primitive human sensibilities, rejecting all reason. The logic here is merciless: where strong reason prevails, patriotism flags; where reason is absent, patriots galore.

It is wonderful that history has created on our little planet so many and varied nations, each one unique. It is wonderful that so many languages are spoken, each one like a lovely song. It is wonderful that each part of the world boasts its own natural beauties. This whole diversity forms a rich and colorful bouquet. The horrors of patriotism start with setting one side against another, one people against another. Worse still: for every patriotic action there is an equal and opposite patriotic reaction. All major conflicts are between patriots. I think everyone would agree that neither material advantages, nor historical contributions give the right of any one nation to consider itself superior to another. The arbitrary generalizations of national characteristics we are accustomed to (as a strange game of knowledge) are more or less false, and everyone, who has done his share of travelling, has encountered kind and generous individuals in each country, as well as rude and discourteous ones – inevitably patriots.

Certain semi-intelligent writers and half-witted officials link patriotism to feelings of national pride. I’ve never quite understood what national pride means. Perhaps, in certain historical periods or certain situations, feelings of national pride have had their significance, but today they are an expression of spiritual malaise, if not of cheap political gamesmanship. I don’t know of a single case, when human pride has injured national pride, but I know of plenty of cases when national pride has injured human pride.

That’s why perhaps one of the greatest achievements of our contemporary world, and most of all of Europe, as a bitter lesson of the horrors of the Second World War, is the ever closer union of people and nations, the emergence of a new generation for whom the opium of national pride ends with ethnography. As more and more Europeans grasp the legacy of nationalism, fewer try to focus their mental energies on proving that France is a greater state than Germany. A shared, natural sentiment of international solidarity pervades the West, gradually erasing national borders and nationalistic claims. We know quite well the significance of the Common Market, as well the drive for the unification of Europe, and all those new and wonderful initiatives which aim to permanently resolve national rivalries.

Even the conservatism of the English, who used to refer to Europe as “the continent” for centuries, evaporated the moment they knocked on the door of that continent and heard the warm, “Welcome!”

Copyright: Annabel Markova

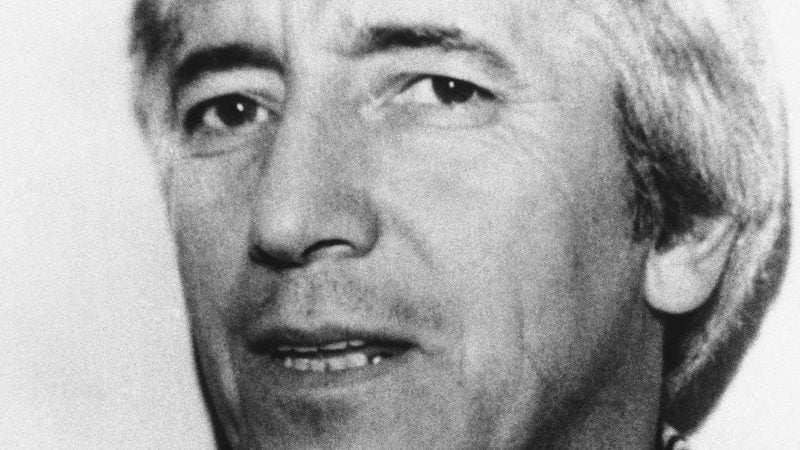

Dimiter Kenarov’s translation of Georgi Markov’s essay, “On Patriotism,” is a feature of our web-exclusive Europe Folio, which accompanies our Fall 2019 Issue on Europe. The print issue is available for purchase here.