Jennifer Sperry Steinorth is the author of A Wake with Nine Shades (2019) and Her Read, A Graphic Poem (2021), both published by Texas Review Press. Her work has appeared in the Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Cincinnati Review, and here at Michigan Quarterly Review (MQR Volume 53, Issue 3 and MQR Mixtape Issue 4). An interdisciplinary artist and C.D. Wright scholar, she lectures at the University of Michigan in the Department of English and the Penny Stamps School of Art & Design. Her Read, A Graphic Poem recently won Foreword Review’s Best of the Indie Press bronze prize in poetry.

I spoke with Steinorth in the spring of 2022 to discuss Her Read, an erasure of Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art first published by Faber & Faber in 1931. The Meaning of Art is both a survey and commentary on the Western canon. In its initial printing, it omitted any and all mention of women artists despite the fact that the female figure was often the subject of the art in question. Beginning this project in the fraught election year 2016, Steinorth transformed this book of art criticism into a feminist verse that resurrects and amplifies voices that have been silenced for centuries. The result is a singular achievement that is both visually stunning and lyrically dexterous.

David Joez Villaverde (DV): You are an educator, a licensed builder, a dancer, an interdisciplinary artist. Do you feel the variety of hats you wear contributes to your lability in undertaking a book as bold as Her Read?

Jennifer Sperry Steinorth (JS): I think it’s fair to say that all my poetry draws from this interdisciplinary way of thinking; writing often feels like an act of translation from dance—movement, corporeal embodiment, physical and emotional sensation. And as with dance, music is a primary engine for my work. Though line is not always king, I often think in terms of other architectural organization—sometimes proximity within a more concrete form creates the musical score. When I began Her Read, I had long been thinking about the movement of the eye across the stage of the page and the various qualities and contributions of vacant space. And though I’m not able to visually “see” in my mind’s eye, I still moonlight as an architectural designer and have a good sense of space, line, proportion, color. I can’t see with my eyes closed, but I’m attuned to what I see with open eyes and can imagine otherwise. Of course, this was critical for Her Read.

That said, I doubt I would have been as bold as I was, were it not for time spent at Vermont Studio Center—the visual feast I tasted in their studios and the encouragement I received from the talented artists there. I was a few months into what would be a four-year undertaking when a visual artist held my book in her hands and said, “Jen, this is art. This is an art book. You are making art.” She asked about a few pen marks I had made and said, “Do more of that.” It sounds silly now, but, as a writer, making marks in that way felt like trespassing. Why did I feel this way, despite the fact that earlier in my career I trespassed my way into both poetry and architecture? It’s fascinating how we insist on these fences for ourselves.

DV: Speaking of barriers, you just mentioned and have also talked previously about having some form of aphantasia. Does this impact your approach to visual art at all?

JS: I don’t know. I suppose because I do not see in my mind’s eye the way some others do, it’s hard for me to imagine images before I encounter the materials. I have to work in order to see.

A thing I like about working with erasure is that the words are right there. In the same way that conversation triggers new ideas, new articulations (this interview for example), in erasure I find myself articulating in ways I wouldn’t otherwise. Similarly, when it comes to the visual images in Her Read—probably 99% of the time—the language came long before the image. And I almost never imagined an image before looking at what was already on the page. The quilt on the penultimate page might be an example. And I knew the last page would be only Wite-Out.

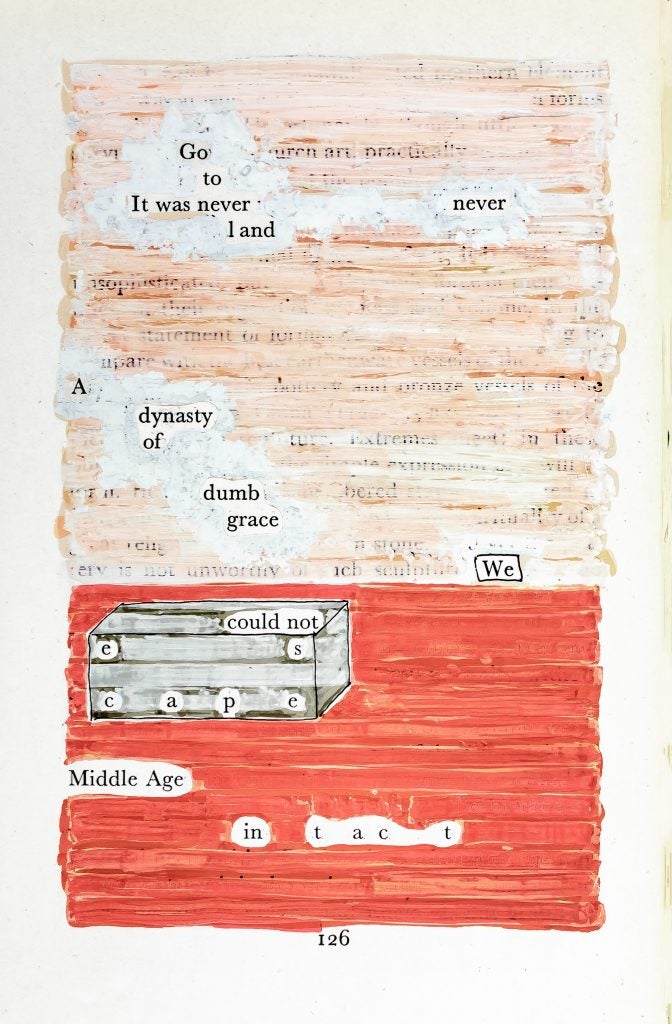

But most of the images arose in conversation with the text. For example, on page 126, the box was necessary to contain the word escape because I was taking serious liberties in spelling out the word that way.

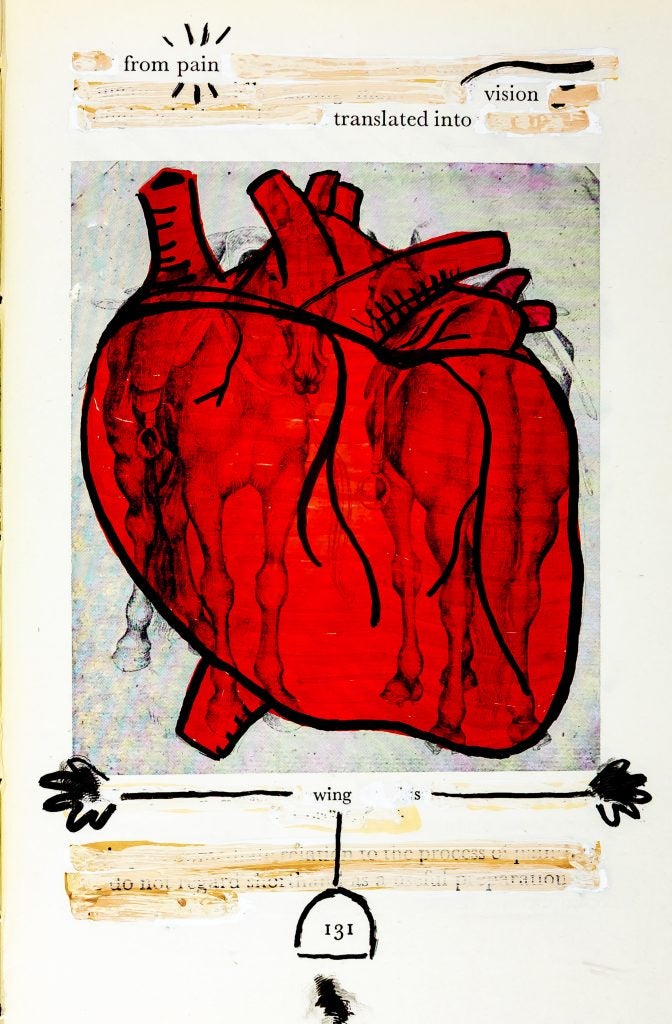

The images on 131, 143, 147 emerged months after the language on the facing pages—but all in the same way, after returning to these images over and over. A heart emerged out of the images of the horses, I saw the sails of ships in the nativity, the shape of a lamb in utero as the image of the dying lamb of God. Clearly there is also metaphoric thinking at work here as well. The heart is an engine—and engines are measured in horsepower. I think I am more of a conceptual thinker. My images are crude, but maybe there is something interesting in the conversational and metaphoric aspects of them that is redeeming.

DV: While progressing through Her Read, I was struck several times by the sheer scope of the collection. It feels staggering at times reading it; it bursts with such artistic dexterity and formal innovation. It really has to be seen to be believed. Did you ever feel overwhelmed in the midst of this project? How far along were you before you realized the ambition of this book?

JS: Yes, absolutely. In different ways, over the course of the book, I felt utterly overwhelmed at the undertaking. In the beginning I was overwhelmed by the bigness of the book I was entering. It was like tiptoeing into a meeting I wasn’t invited to. Not even that. Like making lewd caricatures of the members of a meeting where I had been hired to keep the minutes. But also, it was just a plaything. Part of me thought it probably wouldn’t go anywhere, while another part must have thought it was big from almost the start. The thought that it was frivolous made it easier to go on, but fairly quickly I started to fall in love with the thing. The texture of the correction fluid—the way it reached back to antiquity in pages like these from early in the text:

I think my grief made it possible to not be overwhelmed by the hubris—the ambition—of the book. In a recent interview, Ocean Vuong describes survival as a creative act and that rings true to me. My grief—and my rage—were overwhelming, and this work was necessary to my survival. And of course, that grief, that rage, was a point of connection. I knew I wasn’t special. Doing the work was a way to dig myself out from under the avalanche of grief—one small spoonful at a time. It felt like that—the slow, tedious work of erasure often felt like carving a mountain with a spoon. And I often felt wholly inadequate. A page from the book comes to mind:

But I couldn’t focus on my inadequacies. Because then I would remain trapped. I could only pick up my spoon and work.

I will say, toward the end, in the last pages, I had an experience that felt transcendent. A similar thing happened during the last major revision of A Wake with Nine Shades. I was pinning the pages up on the wall—having submitted at last to an idea I had been avoiding because it felt too difficult—dismantling a long poem and using the parts as stitching to reconstruct the book, a sort of underpinning for the whole—and suddenly I was weeping. Like holding onto the wall and sobbing. Though I wasn’t sad—or happy. It was as though I was touching something deep, something I’d not touched before but was necessary to touch.

With Her Read, it was different but similar. When I got to the end pages—it feels stupid to say this—it felt like touching God. I was overcome. Not like I was God. Or anything grand. More like I was a vessel—the awe of feeling something not me move through me. In the gospel of Mark there is a story of a woman who doctors are stymied by—she doesn’t stop bleeding. She believes if she can touch the hem of Christ’s garment she will be healed. And so, she does and she is. An overwhelming smallness—touching some vast beyond. And again, weeping.

DV: Its interesting you mention this moment of humility that gestures towards something much greater beyond it, as I feel this book very much embodies that spirit. As Her Read unfolds, it expands both poetically and visually. The original three-color palette opens as something akin to Mary Ruefle’s erasures but then expands to become a sort of illuminated manuscript much like Tom Philip’s A Humument. The collection moves beyond color and correction fluid to include embroidery, drawing, and painting… Did your process and palette evolve as the manuscript evolved? Or was this always your vision?

JS: Oh, it definitely evolved. At first, I intended an erasure akin to Ruefle’s style—though I had only seen a small bit of her work. But soon I realized I could not sustain that modality through the entire book (the source text, Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art, was 262 pages long). It would soon get dull. So, there was that. And the linguistic rules for erasure kept evolving as well. I began to see that as the book advanced so did the possibilities for expression. Because I made three complete drafts of the book, I could have gone back to the early pages and elaborated on the images, but the evolution of design, technique, and rules of constraint over the course of the book—a book whose source text is also noticeably advancing chronologically through history—seemed appropriate to the conceit. Over the course of the book, the growth of the speakers’ agency over the materials mirrored the increasing agency of women in recent history.

DV: Speaking of history, conversations with historical figures seem to be an emergent theme in your work, whether its Robert Frost in the billets-doux from A Wake with Nine Shades or Herbert Read in this collection. Each conversation has a form that seems to indicate an inability to see the whole picture (the erasure in Her Read, the “select billets-doux” in A Wake with Nine Shades) and I wonder if you would agree that renegotiations with the power of the past are never adequate? Or do our assertions change the past?

JS: We cannot change the past—what we have done, what has been done to us—all that came before us. Nothing written can be unwritten. But sometimes negotiations, explanations, research can change our perception of the past. Perhaps we have a memory formed by partial information—new information that may alter our understanding. Sometimes, the past has more power over us when it remains unexamined. And sometimes it goes the other way—wading hip-deep—neck-deep—swimming in the murky, under-the-bridge waters gives the past the power of the present. We may be swept away in the undertow. But I am an advocate for talking back to history. Isn’t that what all of us do—as poets, as makers of art, as humans? I love what Philip Metres writes on the anti-epic nature of documentary poetry—its work to create counterarchives that subvert the hegemony’s dominion over the past and, through imaginative acts, to re-member the voids—those people, languages, stories, species, and cultures that have been erased. Poets in this vein are both diagnosticians in the present and archaeologist detectives of the past—roping off the sites of erasure, chalking lines around the body’s absence, populating the void with scents, visions, audible voices. Re-membering the void creates dialogic spaces that to my mind are sacred. Such sites can also strip sanctity from powers that claim it through acts of violence, making visible that which would otherwise remain invisibly invincible.

DV: In this line of thought, Her Read has this wonderful verve that feels very much like a response to the political moment in which it was forged. How do you look at it now, Post-Trump, if we can even say such a thing? That is to say—do you still feel the same urgency that the book seems to contain? Do you feel the culture has shifted in any way or are we still inhabiting the same reality with different actors?

JS: For a few years when Trump was first in office there was attention to this issue. Before that it was gauche; after that it was gauche. There are numerous social issues of grave concern vying for our attention: systemic racism, violence toward LGBTQ+ communities, ableism, ageism, inhumane immigration policies, the corrosive divisiveness in our country, the war in Ukraine, the climate crisis… the list goes on and on.

The reason I began this project was not because of Trump. It was because of what I was personally, artistically, and professionally experiencing in my own life—because of my gender and in spite of my numerous privileges—from “progressive” male (and sometimes female) artists, writers, educators, doctors, administrators. These weren’t new experiences. They weren’t caused by Trump. I’ve been experiencing them for years. And I’m not special. It’s everywhere. Like many women, I have experienced sexual assault. If I had to put all the violences I have experienced out on a clothesline for society to rank worst to least offensive, undoubtedly the sexual assault I experienced as a minor at the hands of a teacher would be called the worst. But—as traumatizing as that was—for me it was truly nothing compared to the subtle, recursively harmful erasures I have experienced professionally, personally, artistically as an adult woman. Violences that are far more difficult to prosecute but that call into question my sanity, my personhood. Violences that even in questioning could jeopardize my career, financial stability, reputation. Again, I’m not special, and have it so much better than so many.

To be honest, answering this question fills me with rage. It’s likely that many people think—didn’t we deal with that already? So, I guess it’s an important question to address. But also, I think, really?

We do not know what a society that gives equal agency to women looks like. Where women are not universally seen as the Object of love, the Object of beauty. There is almost no record of such cultures—it does not exist in our consciousness in a real way. Never mind the public appropriation of, worship of, and simultaneous disdain for motherhood. Millenia of erasing women’s voices—of preventing women from all forms of recorded utterance—Trump has nothing to do with any of this—he just brought it briefly into relief. Our work must go on.