Published in Issue 63.1: Winter 2024

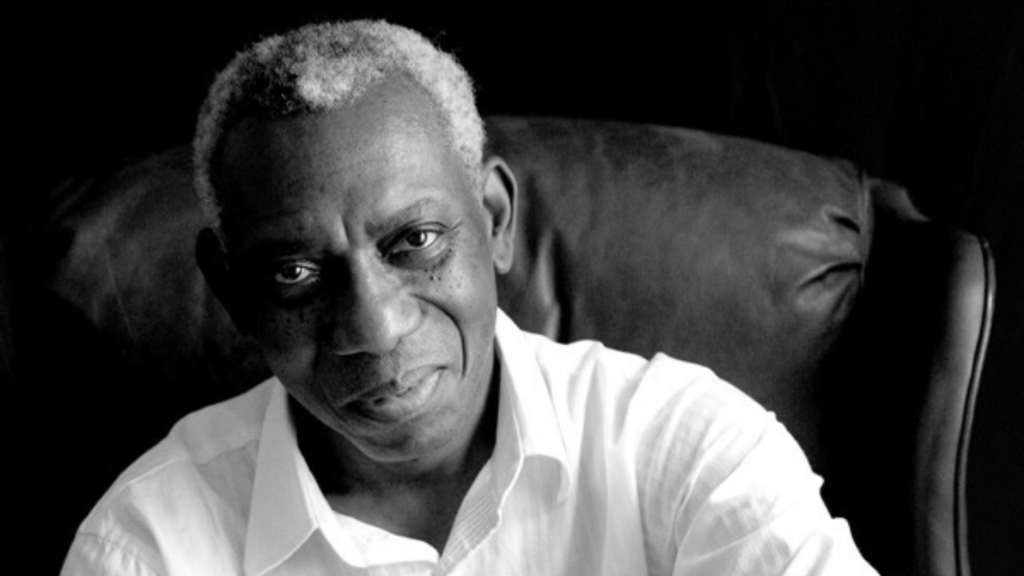

Tenderness and purest admiration is the backbone of this rare gift J.D. Scrimgeour offers us with his essay, “Bloomington.” Magnificently vivid memories rendered in delicately crafted sentences create the window through which Scrimgeour invites us inside the private life of a beloved American poet, the first Black male winner of a Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, Yusef Komunyakaa. It is a blessing to learn that the genius mind that birthed many of the greatest poetic lines in the history of American Literature is generous with his wisdom and kind with his time. “Bloomington” tells us of how Komunyakaa has inspired and mentored generations of poets including some of my personal favorites: Tyehimba Jess and Nicole Sealey. Perhaps this was only a selfish choice after all. Ever since I encountered “Facing It” in my Intro to Poetry Writing class in college four years ago, I have been entranced by the heights Komunyakaa’s work elevates language to, and as a young poet, I aspire to write towards even a glimpse of such glory. Thank you J.D Scrimgeour for submitting this essay to M.Q.R. Thank you for this peek inside the life of one of my heroes.

By writing Bloomington, Scrimgeour simultaneously mystifies and demystifies Komunyakaa as he poses a question to his readers, “Can a man be any more exemplary?”

-Diepreye (Contributing editor at MQR)

In September of 1988, during my first month in graduate school in Bloomington, Indiana, a few of the university faculty gave a reading at a local elementary school on a Saturday afternoon. The reading was in the school’s small lobby, an industrial tiled floor with some twenty folding chairs set out. Yusef Komunyakaa’s Dien Cai Dau had just been published, and this was, I believe, his first reading from it. Jon Tribble, the editor of the Indiana Review, who, I’d already discovered, loved to talk poetry, had told me that the book was extraordinary.

Sitting in my metal chair, among classmates who had yet to become friends, I heard Yusef read “Facing It,” his poem about confronting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in his Southern baritone. I had to listen hard to understand him, and I was too young to realize how rare great poems were, but I felt this one lodging itself in me. It is the poem that has guaranteed Yusef a place in the history of American literature. Roger Mitchell, who also read that afternoon, had a poem about the memorial too. He acknowledged before reading it, with simple frankness, that it was “nowhere near Yusef’s,” that unforgettable final sentence: “In the black mirror / a woman’s trying to erase names: / No, she’s brushing a boy’s hair.”

* * *

That first semester, I took a playwriting course. In it, I was reworking a play I’d drafted the previous year that was set in Vietnam. Though I knew no vets, the war had been central in my thinking about my life. My parents had protested the war when I was young, and the idea of resisting war was, early on, embedded in my consciousness. Still, I was just twenty-three. The war had ended when I was nine.

When I met Yusef at a party before classes began, I leapt into a discussion of contemporary poets, no small talk. Rather than being turned off, Yusef invited me to lunch with him and his wife, Mandy, at the Trojan Horse in downtown Bloomington. With the ignorance and bravura of the young, it took less than half an hour for me to blurt, “You were in Vietnam? What was it like?” He and Mandy exchanged a brief look, we ate some more hummus, and the topic changed.

Later he did share a bit of his experience, but only obliquely. He recommended books: Michael Herr’s Dispatches, Wallace Terry’s oral history, Bloods: Black Veterans of the Vietnam War, and Frances FitzGerald’s Fire in the Lake. He seemed especially interested in PSYOPs, the way governments aimed for your heads. “VC didn’t kill / Dr. Martin Luther King” reads a leaflet aimed at Black GIs in “Report from the Skull’s Diorama.”

He also offered to read my play. He pointed out how many times characters said one another’s names, a rookie mistake. I remember cleaning up the script, deleting all the awkward “Willie”s and “Johnny”s. Yusef nominated the play for a local award from the National Society of Arts & Letters. He may have seen something in me that I didn’t recognize in myself: I could write dialogue.

Sometime in my second year in Bloomington, he proposed we write a screenplay based on the life of James Beckwourth. Beckwourth was an elusive character. When I read about him, I was struck by how uncertain the facts of his life were, in part because he was given to self-mythologizing. He was mixed race, one of the early mountain men who explored the West in the mid-nineteenth century. He lived with the Crow Nation, became a Crow chief, and took a Crow bride. He also served with the US Army and was a fur trader. Some said Beckwourth couldn’t be trusted, his allegiances too complex.

Looking back, Yusef seemed most interested in this complexity: a man who can’t commit to the culture he is told that he belongs to, although he doesn’t exactly fit in—as a Black man, he was an outsider. I may have been more drawn to the varied narratives about him—who could I trust?

We each drafted a scene or two. Yusef sketched the beginnings of a love story between Beckwourth and the Crow woman. But I was in the middle of too many projects, and I needed to be the one to take the lead. It foundered.

* * *

I broke his antique chair.

Yusef let me and my girlfriend (now wife) Eileen stay in his house for two summers while he went to Australia. There were two mourning doves in a cage in the kitchen, and, as instructed, we’d drape a cover over their cage at night. The doves would remind us to remove the cover every morning, cooing from behind their veil at the sunrise.

The first summer I revised a poetry textbook for Indiana University’s correspondence course, a class I’d inherited from American surrealist poet Dean Young, who had attended Indiana a few years before me. I’d work at a tiny desk in Yusef’s front room, and when I needed a brief break from composing, I’d lean back in the small chair planted in the plush maroon carpet, balancing on just two legs, doing what mothers tell children not to do. One day, a crack—and the back had broken. I was younger than my years, clueless about property and value. When he returned, I just told him it had broken and offered to pay for it. And that was the last I heard of it.

One evening, after Eileen and I had minded the house all summer, we had dinner with Yusef and Mandy. As we sat on his wide, wrap-around porch, Mandy said that the house was haunted. “I’ve seen a ghost,” she said. A ghost? I expressed some incredulity. I didn’t believe in ghosts. “He has too,” Mandy said, gesturing at Yusef. Yusef nodded. He said he’d seen his grandfather.

* * *

In May 2019, at a day-long celebration of Yusef at NYU, there were several reminiscences about the experience of being Yusef’s student. One of the event’s organizers, the acclaimed poet Nicole Sealey, recalled how there was always a line of students outside his door, how she was grateful for the hour or two she got to meet with him over the course of the semester. Back in those Bloomington years, Yusef wasn’t in demand. Occasionally there would be a student meeting with him in his office, but just as often, I’d walk in and we’d start talking. I talked more than I should have, listened less.

What did we talk about? We discussed my work a little, his hardly at all. I talked about what I was reading—Beckett’s Endgame shook me up, Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room.

During the buildup to the first Gulf War in 1991, I set about educating myself on the Middle East. I went to the Bloomington Public Library, burning with anti-war fervor, and read a couple books about the Palestinian conflict. One was about Yasir Arafat, “peacemaker.” In one meeting in Yusef’s office, I railed against Israeli cabals and double-crosses. Yusef listened carefully. “Where did you read this?” he asked. Given his own fascination with history and politics, his query was a gentle way to remind me: always consider the source.

This is not to say that Yusef wasn’t against the war. One memorable night in February of 1991 at the Bloomington Public Library’s theater, Yusef, David Wojahn, and Roger Mitchell, along with me and other graduate students, gave a protest reading.

“Every war poem is an anti-war poem,” Yusef has said.

You can read the rest of this story and more great content in out Winter 2024 issue, available for purchase in print and digital forms here.

J.D. Scrimgeour’s Themes For English B: A Professor’s Education In & Out of Class won the AWP Award for Nonfiction. Recent essays have appeared in blackbird, AWP Chronicle, and Fourth Genre. His most recent poetry collection is the bilingual 香蕉 面包 Banana Bread. “Bloomington” will appear in Dear Yusef: Letters and Poems For and About one Mr. Komunyakaa, edited by John Murillo and Nicole Sealey (Wesleyan UP 2024).