Published in Issue 63.1: Winter 2024

My aunt stopped depositing her pension and dividend checks. White wicker utility baskets overflowed with unopened brokerage and bank statements, medical reports, coupons, and co-op newsletters. Ophthalmologist follow-up reminders mingled among a handful of Mass cards, and straggler notes from old friends were stranded between bills. Some loosely bound documents were dated and categorized, others paper clipped—disparity posing as order. Doubled parked bins and a dried floral arrangement sat dead center atop a pintsize dining room table while other receptacles occupied the worn wooden étagère behind a chair closest to the wall. It was a still life of an unsustainable strategy that portrayed her struggle for order and autonomy.

I first noticed Ann’s decline after her beloved Cat had escaped by scampering out the door. My neighbor knocked—laughter trailing in her voice—she was meowing and wandering in the hallway. Since childhood, Ann has had a hearing impairment, which explained Cat’s cries going unheard. When it happened a second time, I asked how long Cat was gone. Hours. Her lack of awareness of Cat going AWOL for hours—losing sight of the animal that was her heartbeat—was alarming. Despite her hearing loss, she did hear the unease in my voice. From that moment on, if I wanted to know about Cat, I knew I had to ask. And when I did, invariably the response, less like her former self, was clipped: Good. Denial prevailed as Ann began to keep the world, and others, including me, at a distance. Going out less, eating less, becoming less talkative.

For years I kept more than an eye on my mother’s sister, though instinctively I knew to keep sufficient distance so she wouldn’t feel boxed in. It was during my First Communion when I recognized the similarity of our temperaments. We shared my bedroom and Ann had risen early. I watched as she quietly struggled to open a window, not seeking fresh air, but because she felt, as I did, suffocated in that house. Turn the latch was all I said before we both broke into laughter.

Two years earlier, she had presented me with her mother’s wedding bands, an envelope of family photos, and a startling statement: I’m willing you my apartment. Those words, spoken with hyper-alertness, made me uncomfortable. Our relationship was never based on monetary or materialistic considerations. I found myself wordless, staring only at her mouth and skipping rope in my head to distract myself from determining what “willing” meant.

In my family, inheritance was complicated and tainted. Giving was attached to leashing and manipulation. Taking pleasure in one another’s company, Ann and I, childfree, had both ceded our bloodlines. Yet when gifts were exchanged, they were always from me to her. Stuck in my throat is the knowledge that to be a giver is to exercise a kind of control. Dad was generous, big-hearted to a fault, a genetic trait. Mom was the exact opposite. She was teased and called frugal, but really her behavior was mostly selfish. Possessions remind me of the cost of inheriting my parents’ contradictions.

When I took the photos, but declined the rings, hurt, not anger, peeked out from her eyes. My aunt had made a rational decision. She wasn’t going to be around forever. Understanding I was meant to have them, I reached my hand out to take the wedding bands. Who would I pass them onto? I couldn’t say that without it becoming about my issues. Then she uttered a phrase that a mother would say to her child. We have the same hands. We did.

·

Ann was mercurial. Whenever Mom spoke about her only sibling, her remarks were punctuated, incomplete: younger—blonde and blue-eyed—slender—nurse— . . . a framing of loose change in a pocket that has some value, but never quite enough. Unarguable was her vibrancy, independence, and grasp of Boston and national politics. Ann and her friends held a deep enthusiasm for subjects including gardening, European history, and Catholicism. To be able to take part in their lively debates, I had to get up to speed beyond my interest in books and theatre.

Decades earlier, when she was a pediatric nurse, a friend’s family loaned her the down payment for her Beacon Hill studio across from the Charles River. The family wanted their daughter and Ann to be close. It was a layered friendship. A partnership? Gender fluidity, unspoken, surged within her collegial community. The women’s apartments, both with small terraces, were on different floors—her friend’s a large one bedroom, Ann’s the better view. Trade-offs. The River House ladies drank, took excursions around the world, and knew their city’s nooks, crevices, and happenings in ways I will never be able to. Ingrained in them was the place where they fell in love, took risks, overcame obstacles, and made their favorite memories. For a lifetime, Boston, more than being custodial or a cradle, was their genesis. In the ’50s when the co-ops were purchased, no one had been thinking that the 221-unit building would essentially become a retirement home.

I have my doubts that Ann, born in 1932, remembers me. The last time I saw her in person was in 2017—June for her birthday, then again in July. Affixed to those dates are sadness and introspection. Had Ann ever even cared to know me? Yes, we had commonality and familiarity, but did a steadfast support for each other exist? Did I matter to her?

She liked cats, clutter, soup, and penne bolognese and collected, to excess, Bon Appétit and travel magazines, paperback books, folded maps, and guidebooks. In 2017, when she called and, with a stumbling voice, asked for help, my husband and I dropped everything and headed to her. Her two words—“having trouble”—spoke geriatric-octaves that no one avoids. I panicked, took control, and wrongfully kept Ann from saying more. The facets of fear are many. Mine steers me into becoming a soldier. I’m not capable of having calm feelings for relatives. When my mother was dying, you could say I took it like a man. My therapist had encouraged me to visit her by drilling into me: Not for her, but for you.

In the car en route to Boston from Manhattan, I thought about arranging home health care for Ann, though I knew she would never agree to it. A deal with the juice bar close to her apartment for morning and lunch deliveries had a better chance. I hadn’t wanted to cry, but when a store manager got on the line with me to discuss a long-term meal program, I hung up. The last three years I had said nothing about her incremental weight loss and laughed at her jokes about becoming more forgetful. However, it was when she stopped drinking—calling it wet brain—then explaining its impact on her vision and balance that I put down my cocktail and asked questions.

What? Is that your doctor’s diagnosis?

She tells me to stay active.

Are you still going to yoga?

I was.

Wet—

I don’t want to drink anymore.

When Ann ends a conversation, the gate slams shut. Though, returning mischief to her smile, she did relent to having a glass of wine on a handful of occasions.

·

For the first twenty years of my life, Ann had little to do with me. Eventually I began to pursue a relationship with her—calling, visiting, arranging dinners and excursions. The obligation to take charge feels biological for me. A need to manage and assume responsibility, though achieving my desired outcomes doesn’t always happen. In the course of getting to know her, I ignored curious, troubling signs and projected onto her what I wanted.

We were a lot alike—thin, blue-eyed, fearful drivers who disliked Mom, her sister, who used to taunt us in the cruelest ways. To me it was done with abandonment: once as a child being told to stay put in a shopping aisle, then not coming back; with Ann, it was declaring that their mother had died because she was born. A common adversary helped to form our bond. She and I meant enough to one another to get us through the holidays with a phone call. Happy Thanksgiving. Merry Christmas. Enjoy Easter. Happy Birthday was missing due to Mom’s animus toward her sister that was managed by the erasure of details about her.

At forty, less afraid of Mom, I asked Ann her birthdate. She was happy I asked. The first day of summer. Yours?

Russian Christmas.

Our zodiac signs were compatible. The water sign brings out the emotional side of the earthy sea-goat, and the grounded Capricorn offers more stability to the crab.

If asked about my life, an inquiry usually linked to family, I circumvent the real question. And my reply is restrained yet tender. My aunt lives in Boston, on Pinckney Street, the Beacon Hill area. To mention Ann had felt more truthful then to talk about my parents or siblings.

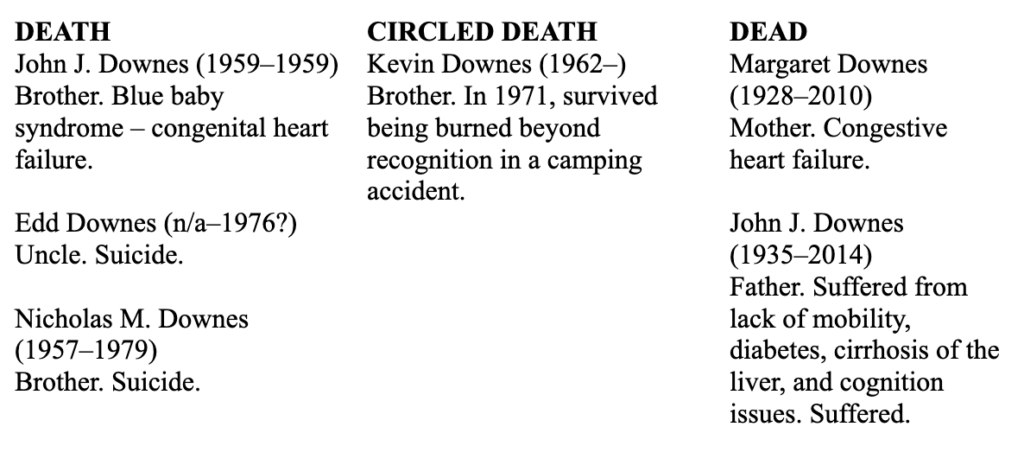

Down the street from my childhood house is a manicured cemetery. It’s the most accurate detail in my life. Our yard was within reach of a landscape dotted with tombstones that marked our losses and burdens of inheritance. A triptych memorial card would have made a jolly handout for me to explain my grief and bereavement indoctrination.

I’m gonna kill myself was said, unsaid, not said, implied, attempted by many family members. How many car accidents were not accidental? A discussion of wills and beneficiaries was notarized chitter-chatter around our dinner table. Bereavement might have first sprung from pediatric grief that plagued my parents. Their 1959 infant was called Johnny, never John. I thought he was a ghost. Uncle Edd, an oddity (even in the spelling of his name), left behind a guitar and a rifle. Nick was never an apparition, though he lived a shadowy life.

The day after it’s discovered that a brother died of suicide, all kinds of contemplations might enter your mind. Mine didn’t include standing on a physician’s scale being weighed by an insurance salesman. At fifteen, I was pulled out of class, escorted to the nurse’s office, and told to step on the durable steel device. Seared into my mind are two poise blocks on parallel bars—the smaller 0 to 50 pounds, the larger 0 to 400.

Survival-stubbornness had made it essential to not stay at home. My siblings followed suit. Waiting for the school bus, we stood silent. On the way to school, as we passed the funeral parlor, I noted that the front window publicized our family tragedy with closed curtains. During the second period, the three of us were collected to have our bodies catalogued.

I had a view of Mom’s car pulling up to the front of the building. We soldiered out, spilled into the vehicle, and returned to our house located up the street from the cemetery where our brother would be buried. Memory’s bandwidth includes drinking 7 Up, watching television, tossing damp, balled-up Kleenexes turned mini-basketballs into a wastebasket, dressing for the 6 p.m. wake, and trying to think of a way to get out of going.

At eighteen, I took over the premium payments of my MetLife insurance policy, which is now five decades old. Twice I’ve changed the beneficiary. When the invoice arrives, shock still registers as it reminds me, fairly or not, of Dad’s Las Vegas odds regarding my life. With our brother’s remains not yet placed in a coffin, the living were weighed and measured. Wasn’t he aware that the first two years of a policy doesn’t cover suicide?

Accurate calibration requires a scale be on a level plain. This simple truth holds its own weight.

Truth: Childhood was a perishable luxury not only for me, but also for Ann.

Lie: Everything in our family was a disaster.

Truth: False measurement is the belief that good and bad must balance.

Lie: Neither Ann nor I has ever weighed over a hundred pounds.

Truthful: This essay is about disillusionment.

False beliefs: exist at the core of illusion.

I hit the wall with my family’s inheritance decades ago. My lineage tips the scale. At times, I’m hurting as much as I did when I was a scared seven-year-old. Loneliness, an heir apparent, is my closest of relatives. A desire for family never goes away. What is the accurate weight of simple truth?

You can read the rest of this story and more great content in out Winter 2024 issue, available for purchase in print and digital forms here.

Yvonne Conza is a writer in Miami. She has words in Longreads, The Believer, Catapult, Joyland Magazine, Pleiades Magazine, Blue Mesa Review, and other outlets. She has been a finalist in many competitions, which has fueled a dogged determination to tell the stories needing to be told. Assistant Nonfiction Editor for Pithead Chapel. She is the co-author of the user-friendly dog training guide Training for Both Ends of the Leash (Penguin).