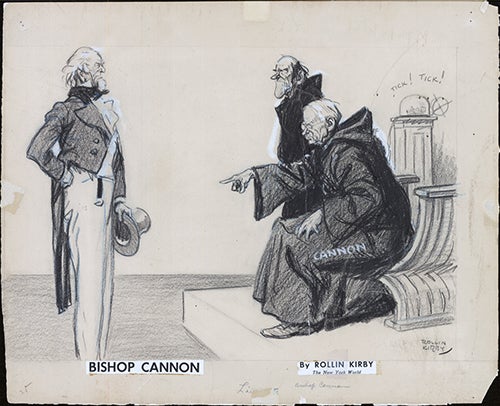

“Bishop Cannon” (ca. 1927)

“Bishop Cannon” (ca. 1927)

by Rollin Kirby (1875-1952)

10 x 14 in., grease pencil on textured board

Coppola Collection

At the time of his death, Rollin Kirby was considered the finest political cartoonist in America and had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize three times, including being the first such awardee, in 1921, 1924 and 1928.

Kirby was a staunch opponent to Prohibition, and created the character “Mr. Dry” in 1920 as the personification of the movement. In an interview, Kirby reflects,

Back in the days when Frank Irving Cobb was editor of the New York Morning World, out of the seething turmoil of the period when we were giving until it hurt, hunting out pro-Germans, and bands were playing Over There, there arose almost unnoticed by the press of America, a wartime measure to help win the war.

Out of the confusion of the time it eventually became the Eighteenth Amendment. Tacked onto it was an act proposed by an obscure Congressman from Minnesota named Andrew Volstead.

Finally the drum-fire ceased, the boys came home and the wayfaring citizen suddenly realized that something extraordinarily unpleasant had stepped into his life. His liberty had been curtailed, for one thing. He resented that. He also saw growing up around him a sinister, hardfaced gentry: the racketeer and the bootlegger.

The tom-toms beat far into the night in the prohibitionists’ camps. They were jubilant, hypocritical, smug and above all else, insolent. They combined what they considered to be virtue with a thin-lipped savagery. They gloated and cheered when a rum-runner was murdered by a prohibition agent. They applied in so far as they were able the methods of Torquemada.

The Methodist Church seized the gonfalon [BPC note: this word needs to be used more often] from the Anti-Saloon League and, aided by the W.C.T.U. and kindred organizations, swept up onto the barricades and thumbed their noses at the bewildered but extremely sore populace who stood huddled in impotent anger in the doorways. They took the Republican party by the scruff of its aging neck and licked all the fight out of it.

But at the beginning of the debacle Frank Cobb and the World, backed by its owners, the Pulitzers, sailed into the fight.

When the press of the country was lying supine under the hob-nailed boots of the Anti-Saloon League, that paper dared to say that the whole thing was vicious, un-American, economically unsound, and a fraud without parallel in our history.

And I, as the political cartoonist, evolved a figure upon which we could hang our displeasure – a figure tall, sour, weedy – something to express the canting hyprocrisy we felt about the movement. And above all something to catch the quasi-ecclesiastical overtones inherent in the thing.

This last element was filled with dynamite, for there is an unwritten law in the Fourth Estate that religion is a sacrosanct subject – that it is not a controversial topic and that any criticism, be it ever so oblique, must never enter into the news columns.

However, Frank Cobb approved of the symbol I had evolved and we printed him.

After that, the deluge. Letters from ministers, professional drys, Y.M.C.A. secretaries and the whole self-appointed crew of field marshals in the new dry army poured in on every point.

But the World was a fighting paper and I drew him again and again. Upon our unbowed heads fell the bludgeonings of the Anti-Saloon League. The Methodist Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals, Bishop Cannon, Mabel Willebrandt, and all of the hired tubthumpers of that unhappy epoch.

Undaunted we kept on month after month and the attack never relaxed.

Then one day in the exchange room of the World I picked up some out-of-New York paper and found a cartoon in which my figure had been used. It was not as anti-clerical as mine but the tall hat and the white tie and the long nose were there and he was labeled PROHIBITION.

Some other editor had taken his courage in his hands and come out against the dragooning crowd we were fighting.

And so, as public opinion changed, the more timid papers joined in with us and my puppet became a stock figure until along toward the end of the nobly intended experiment became as standardized as Tammany’s tiger or the G.O.P. elephant.

As the creator I have seen him change under my hand. He became steadily more furtive, more disreputable, crueler. And then, as the golden flood which once had nourished his veins was diminished, he became even more emaciated. No longer was he a dictator. He became snivelling and whimpering. He was broke. He, who once had browbeaten Senators, Congressmen, national conventions even, stood a patched, unshaven scarecrow holding out a battered tall hat for such largess as could still be wangled from credulous supporters.

No longer was he a tyrant – he was simply an exposed humbug whose fall had nothing of dignity nor anything deserving of pity. And now he is in extremis. He lies on a broken pallet in a forgotten attic with his long, dank hair matted over his brow; his hollow, fanatical eyes burn in their sockets; the unshaven jowl has sunk to the contours of the bones; his clothes are in tatters and on the floor lie the broken tall hat and the skeleton of his umbrella. I shall miss him. He has been a good friend. Days when news furnished little, I could always take him out of his box and he danced to my tune.

James Cannon, Jr. was a pro-Prohibitionist who was appointed as a bishop in 1918. The position gave him platform of national influence towards ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920.

By 1927, and following the death of Anti-Saloon League leader Wayne Wheeler, Cannon was considered the most powerful leader of the temperance movement in the United States, so I have tagged the cartoon to this date as an estimate.

The fall of Prohibition in 1933 follows, at least in part, from Cannon’s highly visible fall from grace over significant corruption charges. In 1928, evidence emerged that he was involved with stock market manipulations, used church money to support the political opponents to Prohibition, and wartime hoarding of food staples. The charges against him grew faster than his friends could deny them.

Although the church court ended up supporting him on the corruption charges and, later, on adultery charges, he was brought up on election law violations by a federal grand jury in 1931. And while he was eventually not convicted of these charges, either, the years of revelations ruined his reputation and contributed to Prohibition’s repeal in 1933.

Rollin Kirby, and the widespread use of the sniveling, bigoted “Mr. Dry,” gets as much credit as anyone for helping the repeal effort. In the last cartoon featuring the character, the now-deceased Mr. Dry was mourned by a rumrunner, a bootlegger, a racketeer, and a speakeasy proprietor. “I was almost sorry to see him go,” said Kirby. “I was almost getting fond of the old bum.”