“Too Soon?” (part 3 of 3)

On Shunga

Shunga, the painted or printed representations of sexual practices and activities, were produced between about 1600-1850 by ukiyo-e artists in Japan. If you are not interested in this topic, go read someone else; you have the choice to click away.

Early ukiyo-e artists specialized in making paintings, but creating prints made the work widely available. Without metallurgy or industrialization, the traditional form of reproduction (once paper was common) was woodblock printing. The main artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed the prints; the carver(s), who cut the woodblocks; the printer(s), who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto hand-made paper; and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works. The prints were produced and sold either as single sheets or—more frequently—combined into book form.

Shunga books (“shunga” means “spring pictures,” a euphemism for sexual imagery) were popular and generally available. The exact historical context for the existence of these materials is not recorded, so it is difficult to understand completely from our modern perspective (and mores). However, there were repeated governmental attempts to suppress shunga, the first of which was issued in 1661 banning, among other things, erotic books (known as kōshokubon, literally “lewdness books”). While other genres, such as works criticizing samurai, were driven underground, shunga continued to be produced with little difficulty.

Colonization by and interaction with puritanical westerners during the nineteenth century put shunga into disfavor due to its explicitly erotic nature. In the mid-1800s, an American businessperson described shunga as “vile pictures executed in the best style Japanese art.” There are reports of Americans being “shocked and disgusted” when Japanese acquaintances and their wives showed off shunga at their homes. In the twentieth century, the historical shunga went further underground and became taboo.

As late as 1975, “no relevant material” existed in the British Museum when art historians would inquire. And even when pressed into being allowed access to it, researchers were told that it “could not possibly be exhibited to the public” and had not been catalogued. It was still too soon, at least by cultural standards. Recall that the fervor over Robert Maplethorpe only happens in the late 1980s.

In 1995, the British Museum staged the exhibition The Passionate Art of Utamaro, which included all of the great shunga works by that artist. And in 2013, the Museum presented a 170-item display, the first-ever dedicated to shunga – Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art.

Getting shunga on display in Japan is noteworthy and recent; from “Time Out – Tokyo” (December, 2015):

After much hand-wringing and controversy, the first-ever exhibition of traditional Japanese erotic art (shunga, literally ‘spring pictures’) in this country is finally happening. Spurred on by the success of a similar, critically acclaimed display at the British Museum in 2013, the organizers reportedly offered this exhibit to around ten museums, only to be turned down by them all – the ‘obscene’ reputation of shunga remains strong in some circles, despite the fact the art is readily available in e.g. book form across Japan. The exhibition was finally taken up by Mejirodai’s Eisei Bunko Museum, usually dedicated to the preservation and display of the Hosokawa samurai clan’s history and artistic fortune. From September on, visitors can rest their eyes on around 120 pieces, but you’ll need to be 18 or older to enter.

Edo Period Original Japanese handscroll shunga picture (c.1680)

Edo Period Original Japanese handscroll shunga picture (c.1680)

by unknown

11.25 x 8.5 in, ink and color on silk, on a paper backing

Coppola Collection

17th Century shunga painting picture: crease marks because it was originally rolled up and part of a long scroll. Still has very nice and clearly visible gold and silver mica (metallic pigments). The ‘Chinese white’ colorant (gofun) used for the female is derived from ground oyster shell.

Image from: Ehon Hitachi obi

Image from: Ehon Hitachi obi

by Kitagawa Utamaro (ca 1753-1806)

Dated: Kansei era, 7th year 1795

10.67 x 8 in; woodblock print on paper

Coppola Collection

Shunga Image (source unknown)

Shunga Image (source unknown)

by Keisai Eisen (1790-1848)

Est. date: Edo period, 1825

14.75 x 9.75 in.; woodblock print on paper

Coppola Collection

On anti-Semitic propaganda

If you are not interested in this topic, go read someone else; you have the choice to click away.

Although anti-Semitic propaganda pieces have been integrated into the exhibits at some of the Holocaust museums, the first-ever dedicated exhibit of 150 pieces of these materials was presented at the Caen-Normandie Museum, in France, titled “Heinous Cartoons 1886-1945: The anti-Semitic Corrosion of Europe,” during the latter half of 2017.

2017!

The materials for the exhibit came from one collector. Since the early 1960s, Auschwitz survivor Arthur Langerman has amassed a collection of 7000-8000 items in this genre, and could never attract the interest of anyone to dedicate a display. And yet, he has argued, these are a key piece of remembrance.

The materials and their messages are reprehensible. But how can ignoring this critical documentation of historical and widespread hatred be the right decision, particularly because the Holocaust was the culmination of generations of overt denigration – worldwide – and not the de novocause that the Nazi regime championed and took to the level of mass genocide? The answer to the question of how such prejudice could happen so quickly is quite clearly that it was not quick at all. The evidence for widespread and explicit mass market hatred goes back to the mid-1800s, and these are statements of widespread historical scapegoating… not a new invention. You could buy and send your friends overtly anti-Jewish postcards from your vacation trip to the boardwalk.

How can 2017 be too soon?

The conversation is intriguing. From a published article describing the Langerman exhibition:

Given the deplorable nature of their message, can any of these works really be called art? “Yes,” says Langerman. But Stéphane Grimaldi, the museum’s director general, disagrees. “These are historical documents,” he says, “they have no artistic value. They’re everything art isn’t.” He refused to put any paintings on display, preferring to focus instead on the graphic propaganda.”

There are two collectors who have probably amassed the largest collection of anti-Semitic propaganda in the US, one of whom is in Michigan and the other in Ohio. Their site is Germanpropaganda.org

A video documentary about Langerman and the development of the exhibit was produced (password ARTHUR).

https://vimeo.com/255065767

“Youpino” (page 3)

unattributed

published by NEF in Paris, ca. 1930-1944

8 x 6 inches, printed on paper

Coppola Collection

Stamp and sticker in rear show this was the property of the Union Populaires de la Jeunesse Francaise, a fascist youth movement.

Plus vieux, it trichait au jeu pour accroitre le nombre de ses jouets. Parce que c’était un Juif!

Older, he cheated on the game to increase the number of his toys. Because he was a Jew!

“Youpino” (page 7)

“Youpino” (page 7)

unattributed

published by NEF in Paris, ca. 1930-1944

8 x 6 inches, printed on paper

Coppola Collection

<Brulez ce blé, sinon les prix de vente vont baisser>

<Burn this wheat, otherwise the selling prices will go down. >

Marié, au lieu de gagner bon pain proprement, Youpino trafique, malhonnêtement pour s’enrichir rapidementParce que c’était un Juif!

Married, instead of winning good bread properly, Youpino trades, dishonestly to get rich quickly. Because he was a Jew!ˆ

“The American Jew”

“The American Jew”

by Telemachus Thomas Timayenis

1888 Minerva Press

Coppola Collection

America’s First Anti-Semitic Author

From: The National Herald, January 25, 2015:

No comprehensive history of the Greeks in the United States can be presented without the inclusion of this problematic individual. In short, Timayenis was a professor, novelist, playwright and one of the first to publish a discourse on what was then known as the Jewish Question along racial lines in the United States, rather than considerations of religious doctrine.

In 1886, Timayenis was the director of the New York School of Languages. By 1887, Timayenis was tutoring the children of some of America’s richest families including the Rockefellers.

In 1888, Timayenis left his academic work and established Minerva Publishing Company in New York, the first company in American to publish books critical of Jews. Timayenis anonymously authored three tracts on the Jews: The Original Mr. Jacobs: A Startling Exposé, The American Jew: An Expose of His Career, and Judas Iscariot: An Old Type in a New Form.

Initially, Timayenis based his accounts largely on the publications of Edouard Drumont, founder of the Anti-Semitic league in France. Various authors adamantly contend that Timayenis’ work spread a permeating ideological fog over the 1880s such that Anti-Semitism gained new ground across the United States.

From the Introduction to “The American Jew”:

We expect that the Jews will try to boycott “The American Jew,” using the same peculiar tactics as in the case of “The Original Mr. Jacobs.” They will appoint committees to visit book-dealers, urging them not to handle the book; they will buy up and destroy all copies found exposed for sale; they will bribe, threaten, plead, and try in every possible way to interfere with its sale; they will circulate reports that the book has been “called in,” and will spread many other lies – lies that the Jew knows so well how to disseminate.

On Nanshoku

As with most ancient cultures, there is a history of men who have sex with men that dates back for millennia. If you are not interested in this topic, go read someone else; you have the choice to click away.

When one talks about the way culture and media provide a social construction of ideas, it is important to recognize that even the term “homosexual” and its appended concept is strictly modern and derives from fairly puritanical European and American roots.

With the rise of shunga in the Edo period, depictions of male-male interactions were not in dedicated volumes, but mingled (albeit infrequently in an absolute sense) within the shunga volumes. One’s role as the dominant or submissive partner was a more critical identifier than one’s gender.

The male-male shunga, called nanshoku (male color, using a character for “color” that was associated with sexual pleasure), ran the representational gamut that one finds in the ancient cultures: the young-old, perhaps pederastic relations found in monasteries and the military, male prostitution among young actors, to nothing more than humorous situations and acrobatic sex acts.

In the last 20 years, as collections of shunga have become available, some authors have written about the occurrence of nanshoku within shunga, but there has never been a studied exhibit of this taboo within the taboo.

Perhaps it is simply too soon…

From “Sokuseki Joritsu” (in three books)

Images by Utagawa Kunisada (1785-1865)

Text author:Sanenaga

Size: 7 × 5 in, 18-22 pp each, woodblock print on paper

Date: Late 19th century

Coppola Collection

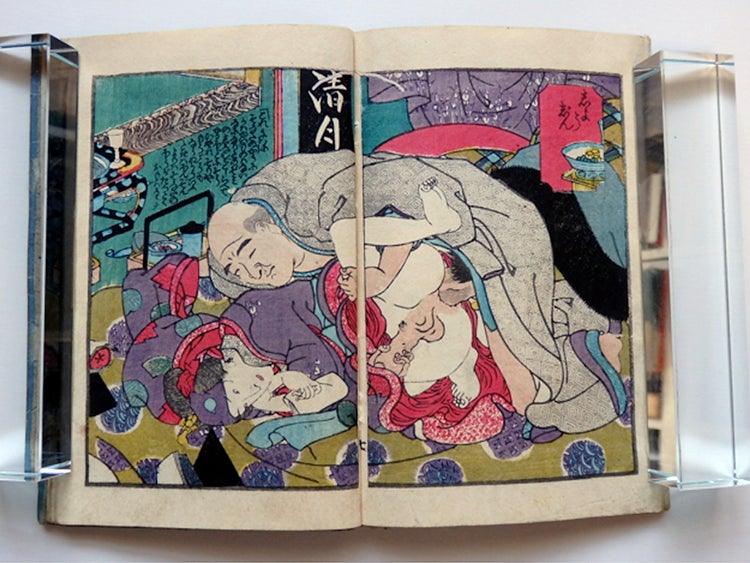

From “Makuro Bunko” (Pillow Collection).

From “Makuro Bunko” (Pillow Collection).

Images by Keisai Eisen (1790-1848)

Size: 9.5 x 8 in., woodblock print on paper

Date: c.1823

Coppola Collection

From “Baibobo sensei injoho” (Mr Pussybuyer’s Erotic Treasures)

From “Baibobo sensei injoho” (Mr Pussybuyer’s Erotic Treasures)

Images by Terasawa Masatsugu (?-1790)

Size” 8.67 x 10.67 in., woodblock print on paper

Date: c. 1760

Coppola Collection