1933.03.20 “?”

by Charles Henry (Bill) Sykes (1882-1942)

14 x 17 in., ink on coquille board

Coppola Collection

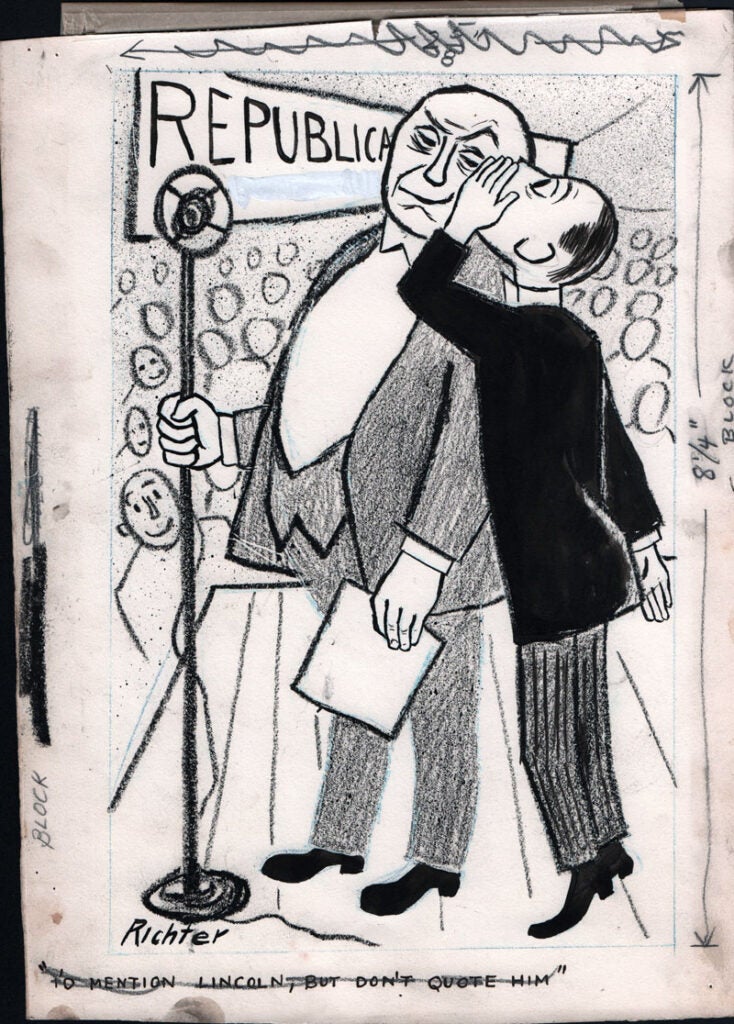

Sykes was an American cartoonist associated with the Philadelphia Public Ledger and Evening Ledger from 1911 until its closing in 1942. He was the regular editorial cartoonist for LIFE magazine (1922-1928) and a regular contributor to Collier’s and the New York Evening Post. Sykes’s early work was distinguished by usage of coquille board for shading. His later work incorporated crayon and wash. Sykes’s technique was described as “amiable. His perspectives were unique, his anatomy precise, and his shading almost theatrical.”

This example is particularly well done, representing the artistry of cartooning.

FDR and the Three R’s: Relief, Recovery, Reform

FDR’s inauguration was early March 1933. On March 6-10, President Roosevelt declared a national banking holiday as a prelude to opening the banks on a sounder basis. The Hundred Days Congress/Emergency Congress (March 9-June 16, 1933) passed a series laws to help improve the state of the country. This Congress also passed some of FDR’s New Deal programs, which focused on: relief, recovery, reform.

Short-range goals were relief and immediate recovery, and long-range goals were permanent recovery and reform. In the New Deal programs, Congress gave the President unprecedented “blank-check” powers, which included the ability of the President to create legislation. The New Deal legislation embraced progressive ideas like unemployment insurance, old-age insurance, minimum-wage regulations, conservation and development of natural resources, and restrictions on child labor. Many of the programs that gave the President this authority were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

The authority of the FDR presidency never went away. In an editorial written in 1936, in the November 11 edition of The New Republic title “Mr. Roosevelt’s Blank Check,” the staff writers posed that “if Mr. Roosevelt has any mandate from the electorate, it is a mandate to remain President and do what he wishes.”

“What will the administration write on this blank check? A reelected President is said to have an immense opportunity to act as a leader unhampered by practical politics. During his first term he is making a record for reelection; during his second, since according to custom he cannot run a third time, he is making a record for posterity. This dictum seems to us superficial, especially in the president circumstances. No President, in spite of the great power of his position, is a dictator. And even dictators have to conform with social forces in the end. What any President of the United States can do depends in large measure upon his control of Congress, his support by public opinion, the interaction of pressure groups. He can express ideas, he can wield the prestige of his personality and his office, but the limits of his effective action are determined by forces outside himself.”