By Sebastián Encina, Collections Manager

Every summer, members of the Kelsey Museum community travel to Italy to participate in a number of projects. Many excavate at the site of Gabii (one of three sites currently featured in the exhibition Urban Biographies). Some work for the American Academy in Rome. A few work at Sant’Omobono. Some students do all of these things, all while doing their own research.

For many students, their first time visiting Rome must include some of the highlights, including seeing the Coliseum. This structure has been a destination for tourists and scholars for a long time — long before tourism was big business. Back in the 1800s, traveling was expensive and tedious and took a long time. There were no planes, so getting to Europe from the United States required a long voyage by ship. In addition, not many people had the funds to engage in long-distance travel. For these reasons, tourism did not happen on the scale it does today.

For this month’s “From the Archives,” we present a photograph showing the Coliseum as it looked back in 1885. Images such as this one were taken by professional photographers who would package several photographs together and sell them to schools or scholars or churches. They’d come in series, such as “View of Rome” and “View of the Holy Land/Palestine” and “Views of Greece.” People bought these photographic souvenirs in order to show their students, congregation members, and friends back home what Europe looked like.

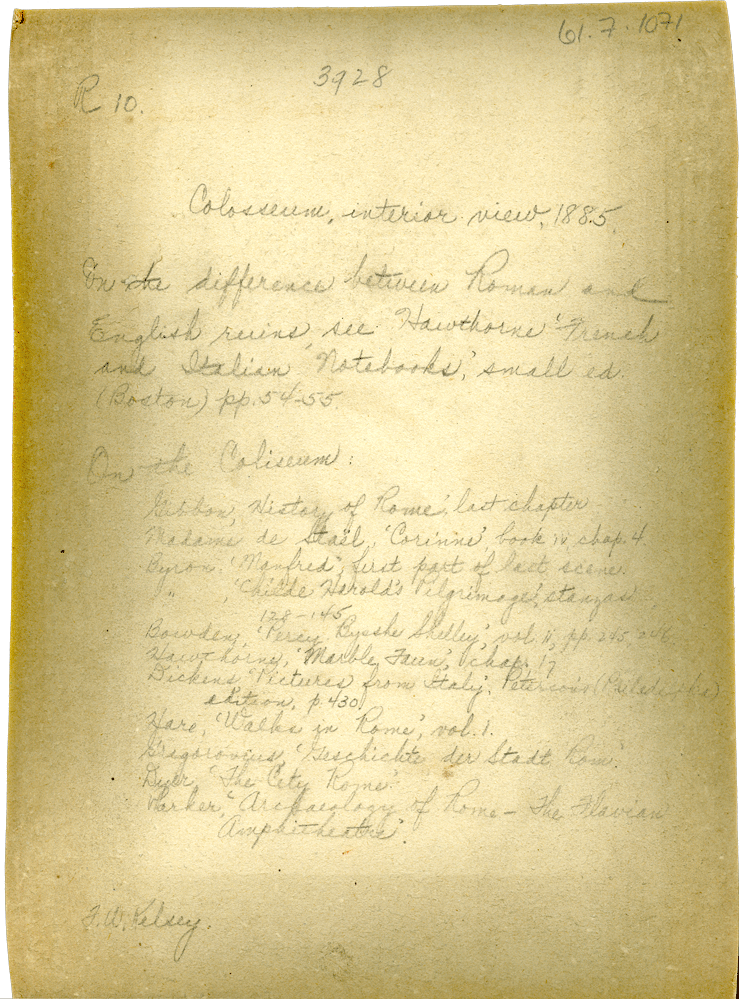

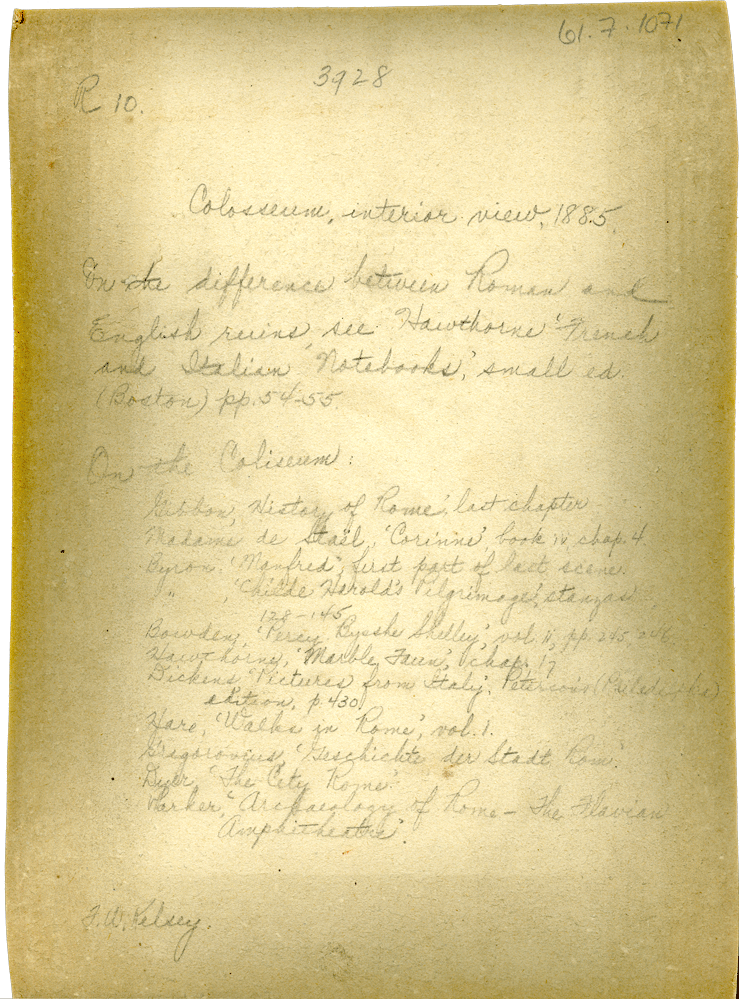

However, the image of the Coliseum depicted on the obverse (front) is not the focus for this month’s post. Instead, we flip the image over to discover the following:

R10. 3928

Colosseum, interior view, 1885.

On the difference between Roman and English ruins, see Hawthorne ‘French and Italian Notebooks,’ small ed. (Boston) pp. 54–55.

On the Colisseum:

Gibbon, ‘History of Rome,’ last chapter

Madame de Staël, ‘Corinne,’ book iv, chap. 4.

Byron, ‘Manfred,’ first part of last scene.

” , ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimages,’ stanzas 128–145.

Bowden, ‘Percy Bysshe Shelley,’ vol ii, pp. 245, 246.

Hawthorne, ‘Marble Faun,’ chap. 17

Dickens, ‘Pictures from Italy,’ Peterson’s (Philadelphia) edition, p. 430.

Hare, ‘Walks in Rome,’ vol. 1.

Gregorovius, ‘Geschichte der Stadt Rom.’

Dyer, ‘The City Rome.’

Parker, ‘Archaeology of Rome – The Flavian Ampitheater.’F.W. Kelsey

Here we have a handwritten note from Francis W. Kelsey himself, namesake of the Kelsey Museum. Not only is Kelsey sharing his comments and thoughts about this image and the Coliseum itself, but he is also giving us vital information. To people who work in archives, learning a particular person’s handwriting is a big key in deciphering other archival materials. Here, we see and can now learn to recognize Kelsey’s penmanship (though it does change as Kelsey ages). Now whenever we find unattributed notes in the archives, we can compare them to this signed note. If they match, we can safely say it is Kelsey’s note we found. And from that, we can start piecing together dates, context, and perhaps even the people being discussed.

Kelsey likely did not think of this as he made this annotation on the back of this photograph. To him, this was just a good location to make a note that would be useful to others. His concern was more for the scholarly aspect of the note rather than the archival one.

Archivists are routinely making discoveries when working in the archives, and they get to know the people captured in those archives. From their notes, we know what kind of workers they were, where they vacationed, about their relationships with family and colleagues, and their general thoughts about the world. Deciphering someone’s handwriting is a big tool for us, as it helps us piece together the archives and, often, people’s lives. We learn so much more about them from the tiny little memories they left than they ever could have imagined.