By Sebastián Encina, Collections Manager

These days, museums have many tools at their disposal that allow us to do our work efficiently. Chief among them is the database, a way to organize our collections so we can find items easily using any number of search terms and tricks. A database can be a spreadsheet, a custom-made software solution, or a large entity that spans institutions. There are many answers to the database question, and no one system is correct. Each has its own set of features that museum staff can’t do without, just as each has its drawbacks.

Of course, many museums were founded decades, even centuries ago, before the advent of computers. How did museum staff track their collections before there was a computer on every desk? How did they keep track of the objects in their care and provide support for ongoing research?

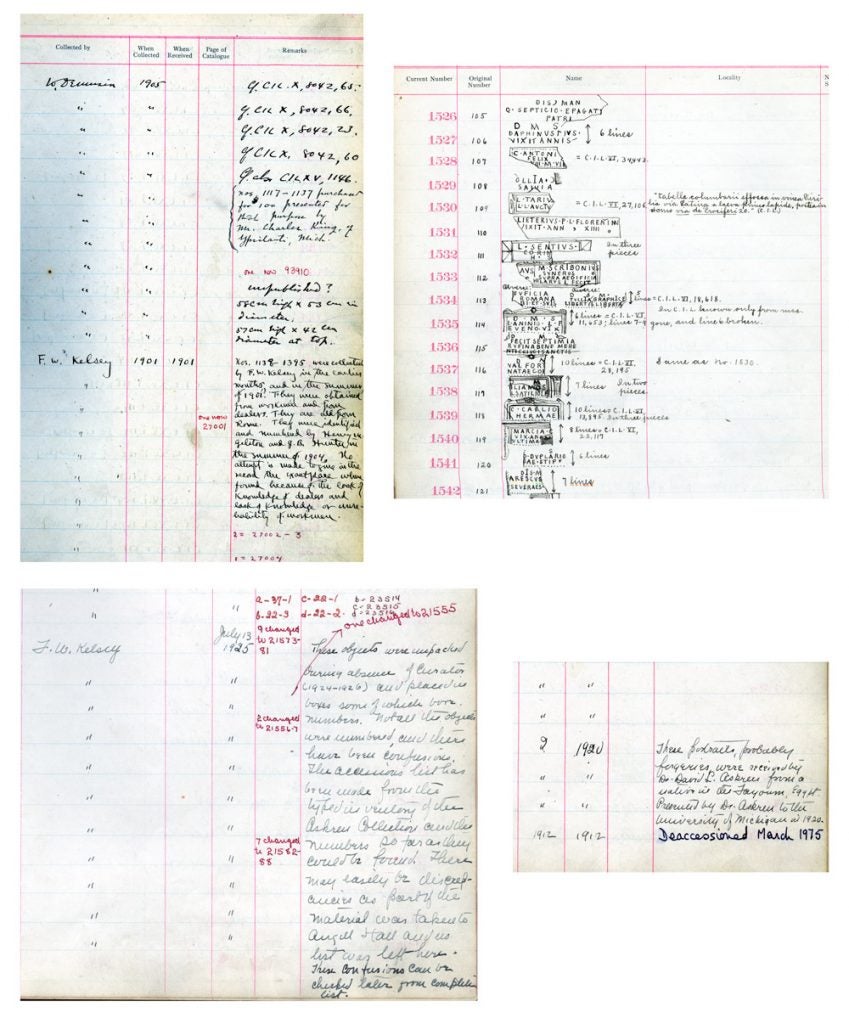

For this month’s “From the Archives,” we present the Kelsey’s earliest form of collections-tracking: the accession ledger. The ledger is an item-by-item catalogue of objects, logged as they were acquired by the museum. These ledgers predate by decades any electronic collections management system and for a long time were the only way to track collections. Even Francis Kelsey contributed to the ledger; his handwriting is found throughout the documents.

These early ledgers provide much useful information to researchers and museum staff. We see not only what materials were collected but also where they came from and when they arrived at the museum. In some cases, we even see when they were collected in the field, as that date may differ from the museum’s acquisition date. On rare occasions, someone included a hand drawing of an artifact. This is more common among some ledgers than others, but it is time-consuming and not all items were afforded this luxury. We see how an item was subsequently deaccessioned, the process where an object is officially removed from the collection. In some cases, information is provided about where the item ended up. In most cases, we do not have that information.

The Kelsey Museum created its first database in the 1980s. At that time, the information in the ledgers was transferred to a card catalogue, and those cards became the basis for the database. The cards did not include all the information found in the ledgers, however. Transcribing everything would have taken a lot of time, and in addition, early databases had limited capacity. In the decades since, we have attempted to add the missing information to our database. It is not always easy. We cannot transfer drawings, for example, and some of the handwriting is difficult to decipher. Fortunately, the longer we work with these documents, the more familiar we become with the handwriting of specific people, and thus more adept at deciphering their notes. And by recognizing handwriting, we can also see how many people were involved in supplying information to each object.

Despite our ongoing efforts, the Kelsey accession ledgers remain full of vital information not found in our database. As we continuously research our collections, we often refer to these ledgers and find new insights. Regardless of how indispensable our databases are, we will continue to preserve our ledgers, for we still have so much to learn from their pages.