Caroline Roberts, Conservator, and Leslie Schramer, Editor

Greetings, Ugly fans! How is it already September?? Time has no meaning anymore … but luckily, we have our Ugly Object blogroll to keep us centered.

We have a special treat for you today. That’s right, it’s a DOUBLE UGLY since, whether you noticed or not in the mad days of the bygone summer, we sort of failed to post July’s Ugly Object.

Though separated by time and distance, these two Uglies have a few things in common. A) They are arguably NOT so ugly, and B) they are not what they appear to be. Let’s meet them, shall we?

The first object is a painted portrait of a woman that was purchased by David Askren, a colleague of Francis Kelsey’s who worked as a physician at the United Presbyterian Hospital in Asyut, Egypt, in the early 20th century. The portrait (along with two similar portraits purchased by Askren at the same time), is now believed to be a modern forgery.

Thanks to our new NEH–funded XRF spectrometer, we now know more about the paint materials that were used to create this portrait—and it seems to confirm what our curators have long suspected. We found the elements barium, iron, lead, nitrogen, sulfur, and zinc in the background and in the woman’s hair and robe, as well as cobalt in the blue beads of her necklace. These are consistent with barium sulfate, cobalt blue, and zinc white—pigments that were introduced in the 18th and 19th centuries.

We can learn a lot from forgeries like this one. For one thing, it demonstrates how the demand for Egyptian antiquities in Europe and the US drove some ethically dubious practices, from the production of fakes to the commodification of real artifacts, in the early 20th century. It also provides comparative physical evidence—pigments we would expect to see in a forgery from this time period—that can help us better separate authentic ancient portraits from fakes. Empirical evidence is key, my friends.

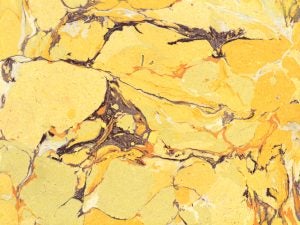

And speaking of fakes, check out this little guy. Looks pretty nice, right? Like a beautiful, polished sample of giallo di Sienna, I bet you were thinking.

WRONG!

You’ve been pranked! It’s not giallo di Sienna at all. It’s not even stone!! It’s a piece of plaster that’s been painted to look like stone! Because, why not? Why cut and polish a piece of relatively common stone when you could sacrifice many hours and possibly your eyesight adding painstakingly realistic details of veining and color to a rectangle of plaster with no apparent function other than to look pretty?

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. I’m a big fan of art for art’s sake. I’m just saying.

This little curiosity was given to the Kelsey Museum in the late 19th century. According to its Kelsey Museum accession record, it once belonged to a “Miss Wanere,” who gave it to the Kelsey on January 10, 1896. We don’t know where she got it, or why she had it. But evidently, she thought it belonged in a museum of antiquities.

We don’t know a lot about this particular piece, but if you’re interested in the biographies of chunks of stone in the Kelsey Museum, you happen to be in luck. The Kelsey has over 700 pieces of ancient stone (yes, I’m aware that virtually all stone is ancient. No lectures, please.) fragments from various quarries and archaeological sites around the Mediterranean. Most were gathered (picked up, purchased, found) by Francis Kelsey himself, who liked them for teaching demonstrations. Others were donated by friends and acquaintances who no doubt knew of Kelsey’s penchant for old rocks of a decorative or architectural nature. All 700+ of these stone fragments (and this one stone look-alike) have been carefully studied by Michigan-affiliated scholars J. Clayton Fant, Leah E. Long, and Lynley McAlpine, who have written a nice little book about them. The illustrated catalogue, which is currently in production here at the Kelsey, focuses on archaeological context and object biographies, following each piece from its creation to eventual deposition in the Kelsey Museum.

We look forward to the day when we can announce the publication of this catalogue. In the meantime, you can come to the Kelsey and see a sampling of these marble fragments in person. They are on the second floor, tucked away in the drawers beneath the Roman Construction case.