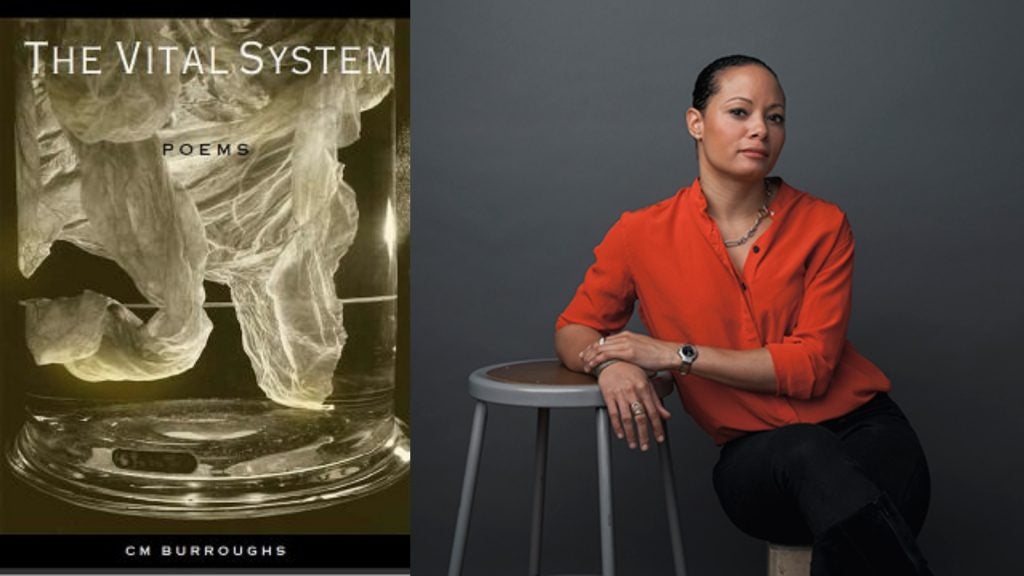

The taut lyric pitch in CM Burroughs’ first book of poems, The Vital System, plumbs “the protective capability of violence” through the body – variously and simultaneously sick, woman, Black, lover, sister – in moments of precarity and power. I met Burroughs when she guest-facilitated my MFA poetry workshop one evening last fall. She approached draft poems through the lenses of radical revision and blade-sharp attention: a wild precision evident in her work.

I was so glad to continue our conversation during her return to Ann Arbor as a Zell Visiting Writer this October. Below, we talk about the “immortal surprise” of writing; the mapmaking book vs. the next book; living and working in Chicago; the body as “first place;” her debut The Vital System (Tupelo Press, 2012), and forthcoming second collection Master Suffering.

CM is Associate Professor of Poetry at Columbia College Chicago and holds an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh. She has been awarded fellowships and grants from Yaddo, MacDowell, Djerassi, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Cave Canem, among others, and her poems have appeared widely in print and online journals and anthologies.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Isabel Neal (IN): Thanks for sitting down with me, CM. I want to begin by asking about what you’ve called the “needle” of the poem, the urgency or momentum that drives it. Do you look for that urgency as a point within the poem? As a point spurring the making of the poem?

CM Burroughs (CMB): It’s both, really. What I see happening is that the writer is arrested by some new discovery, some new impulse that they didn’t understand they had until they were within the poem, writing at their subject. If you write urgently, honestly, I think that it can be easier to be surprised by your own thoughts, your own verse. And that surprise happens many times. Twice, essentially: once for the writer; again for the reader. It’s something that is immortal.

IN: In spending time with The Vital System, I hear a resonance between the last lines of the first poem, “Dear Incubator”: “I love you but, believe this, I mostly want to talk.” and a later line from “In the Personal Camp: Eroticism”: “your mouth opens with sight.” What do you make of the slip between language and perception in these erotic or autoerotic experiences?

CMB: I like that you link those two moments. The mouth opening with sight is a way of saying that the body and its experiences is the way toward understanding, so that, let’s say in love, or in grief, how the body operates matters to what you understand about yourself and the other, yourself and the world.

IN: Throughout The Vital System, body and voice are lush, fractured landscapes; often operating as the setting or site where the poems take place. However, there are few moments of geographic location in the book – notably, a scene of driving in Virginia. How does Chicago, where you have been based for the past several years, operate within your poetics?

CMB: I don’t tend to ground my poems in actual places. But the body gets bigger, such that it’s always the place – or, at least, the first place.

I move well in Chicago; my body is happy in Chicago. The city’s energy is in harmony with what I need in order to sit down, be still, and have the capacity for a poem. That quiet, enough to be able to breathe, to understand what I need to write about.

I don’t think that’s easy in, say, New York. Things there are faster, more hectic, and can induce some stress. I appreciate places that have a lot of vibrancy, but where you can quickly find the still space. And when I say that, I mean that in New York, it’s probably going to take a lot longer to get home to your quiet space than it’ll take to commute in Chicago. There’s not quite as much that can happen in the amount of time I’m en route in Chicago. My silence isn’t too disturbed to write.

IN: It feels important as poets to address this: what it takes to create a container for writing, the actual transit involved. That reminds me of the way you negotiate registers of speech in The Vital System, particularly the pivot between medical language and the lyric mode.

In thinking about vibrancy as community, who are the poets that feel important for you – always, or perhaps in this particular moment of writing?

CMB: There are my mentors. For me, people like Claudia Rankine, Toi Derricotte, and Natasha Tretheway. It’s not that our poetics are so similar, but as people we can feed one another. There is nourishment there. They ask me to allow them to be my vehicle, and this is a really compassionate thing; these poets as people have allowed for a kindred communication.

IN: Reflecting on nourishment and compassion hints at the numinous, the divine. I know that Master Suffering, in contrast to the first book, is framed in part by faith and skepticism, new kinds of perception and an engagement with spirituality.

CMB: Yes. The Vital System is an exposing book, but its lyric properties also require a reader’s investigation and a certain commitment of readership. Whereas Master Suffering is more exposing of me. My self was at stake in The Vital System as I was trying to figure out things like grief, body, illness, love, kinship, romantic relationships. In Master Suffering the speaker has arrived to some understanding.

With the second book, I was allowed to see the entire map. The cartography was made in The Vital System, and I could walk through it, point to things, investigate them in a plainspoken way. My speaker in Master Suffering can talk to herself about experiences that are in The Vital System with more information around them, more context.

It’s just a different way of speaking, really. And it’s not always comfortable for me, but I know that the poems in Master Suffering access new understanding, and have the ability to articulate them clearly. Poems in The Vital System were in the thick of things. It was the middle of the action, where you can’t always see everything.

Douglas Kearney has a line in a poem that goes, “at the edge of it, you’re in the middle of it.” That’s how I feel about The Vital System. Whereas in Master Suffering, the edge is a place of perspective and survey and sense. Where you can appraise.

IN: Can you talk more about your relationship to that discomfort?

CMB: Though I never expected my poems to always speak the same way, in 2012, when The Vital System came out, I also didn’t realize that all the bodies in the book were ones that could transform over time, could be more plainly – and I mean closer to narratively – addressed.

I’m used to a certain amount of experimentation with syntax, and diction, and even form, but Master Suffering is a book that attempts to have control, at last. This in contrast to the Vital System, in which there was an urgency – and an impossibility – of being able to control anything. Master Suffering can actually wield some power.

Because the poems have truth and honesty within them, because I wrote them from a pure place, I can feel uncomfortable about how they speak but I also – and this may be strange to say – don’t have so much control over how they need to speak.

IN: So the control is located within the poem itself?

CMB: Right, within the intention, the need to say a certain thing.

IN: In two of the new poems [“Our People I” and “Our People II”], I’m struck by the “different way of speaking,” as you say, into a Black collective subjectivity, a claiming.

CMB: Those were particular because I was writing toward Gwendolyn Brooks. It was a way to address her by imitating her gaze and her preoccupations with the we, the collective, and the collective concerns. I needed to be more inclusive in those poems, to try and articulate some larger truths or to assert truth that was in harmony with hers.

IN: This brings me back to my first question, about momentum. We spoke yesterday about the experience of having prepared for something, the feeling of being ready – and then there is time before the event. Is that an experience you’re having with your forthcoming book, out January 2021?

CMB: Yes. It’s a gorgeous thing to have that field in front of me, that has no markings, that has not been mapped. And to have a couple of made maps already. I look back over them; I think about what they achieved, what I discovered from them, how I was surprised, and now I get to think a lot about what else is meaningful enough to compose.

And, wow, that can be elusive! I’m a slow writer, a patient writer, and I don’t have qualms about taking the time I need to consider my ideas, consider angles of approach. I’m comfortable with not knowing what’s next. Sometimes it’s the process of the thing that gets me to the thing.

And the time after a book is complete is exciting. One, because something is finished. It’s been stamped with approval, the publisher’s getting ready. And it actually takes a year, from contract to being in your hands, so there’s a lot of that wait time. For this reason I’ve been pushing off solicitations for gigs until late 2020, 2021, so that I can give someone the fabric of the thing as I read to them. I think it’s important to have the artifact.

IN: What appears, as of today, in “that field…that has no markings”?

CMB: Curiosity is important for me. Reflecting on the day-to-day, finding out where my motivations are, what I lean in toward.

In Master Suffering, spirituality and religion was something I was curious about, and it was talking with others that gave me meat to reckon with. That’s a part of that field that I don’t think I’m done discovering.

IN: Thank you so much, CM