You are here because you have recognized the trap of the “Middle East” or have just fallen into it. The trap is the Middle East as a made-up thing, a construct of history and treacherous geography, the Middle East as an American trope, a stage for identity politics.

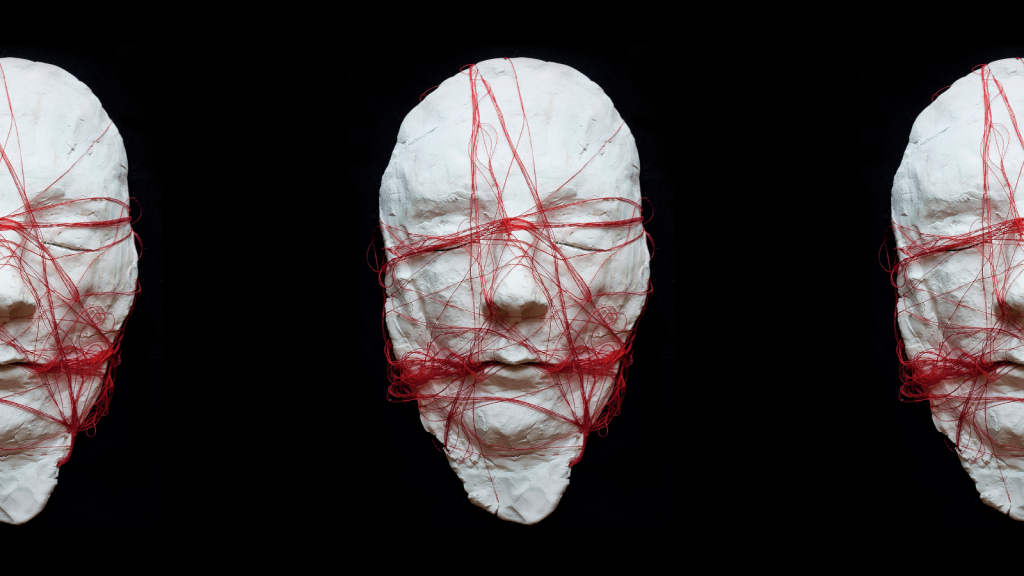

In the American minefield of labels and acronyms (Middle East, Near East, MENA, SWANA, etc.), many of us, who are originally from the countries of the region, learn to contort ourselves and our experiences, to translate them for another, a curious, cautious, interested, alarmed, sympathetic, suspicious other. On that erected stage, we learn to perform the script dictated by these labels, in niche areas of engagement allotted to us in universities, in the media, on the job market, on the pages of a literary journal, in the headlines and the subtexts of the knowledge produced about this region. We learn to compromise our histories, realities, and futures to maintain a myth of ourselves that is more credible than we are and with more currency.

And so, varied and disparate lived experiences, artistic traditions and breakthroughs, moments of strife and repose, rich literary traditions, and urgent practices are packaged, flattened, and co-opted into the self-serving discourse of conflicts, equivalences, balances, and congruent perspectives.

From our vantage point here in the United States and through our gaze in that other direction, towards a distant other we can label, fence in on a map, and in whom we can express vested interests, we invent the Middle East and all its variations and propagations. Many distortions/illusions dictate perspectives on this region in the United States and the world today, including the all-too-exhausted binaries of modern and pre-modern, self and other, East and West, and so on. These distortions not only create an image or a reputation for that region, but they also create a self-image that is marketed back to the subjects of the region and imprinted on them through neo-colonial structures of economy, politics, and education.

Regardless of long and rich literary traditions which have been in a vibrant conversation with each other for centuries, the literatures of the region are perpetual newcomers, “nascent” or “emergent,” waiting to be “discovered” by an uninformed and tangentially interested reader, framed and suspect until they prove themselves worthy or in service of some urgent current extra-literary interest.

A special issue titled “Decades of Fire” on the MENA region is a trap we’ve erected and stepped right into. Don’t we, scholars and students of the region, its translators, artists, and translated subjects, already inhabit that trap? Haven’t we acclimated to it and learned its language? So why not start from here, from our tropes and tools, and see what insights another collation or arrangement might bring?

“Decades of Fire” documents the region’s political, social, and cultural transformations in the last three decades, not because we have privileged the narrative of war and victimhood, but because there is an inescapable reality with which the writers in the region and its diasporas creatively and deliberately continue to grapple. Since the US storming of Iraq to violently establish a “new world order” to the “Arab Spring” in 2011 and its yet unfolding reverberations to the most recent American withdrawal from Afghanistan, these three decades have shook and shattered the region’s economies, its infrastructures, and its social and cultural networks.

These three decades have been shaped by outsider imperatives and unchecked hegemonies, American and otherwise, bringing to the foreground of our consciousness the region’s longer history of revolutions and disappointments since the beginning of the twentieth century. It is impossible to account for these past three decades without threading them in memory to earlier moments of revolution and anti-revolution, uprisings and catastrophes: from anti-colonial activism to movements of independence to civil wars to the persisting question of Palestine, its Nakba, and the moral reckoning to which it continues to summon us, all of us, those implicated in the predicament that is the Middle East.

“Decades of Fire” might have lured you with what you know in the hopes of presenting you with what you don’t expect: experiences of pasts, presents, and futures unlike those recorded in textbooks or anticipated in expert reports, languages within languages for which no rubric or pedagogy can account, landscapes of imagination that will not fit squarely into “objective” histories and imposed timelines. Read these collated texts each on its own terms. Let each of them attempt, as all art does, to be the end of an era and the beginning of another. Don’t burden them with history. Allow them to overcome it and be texts that can stand or fail on their own. Let the works included here tempt you to a journey towards the many other works which are not. Let them be doorways to more complex and nuanced worlds of experience and art which could not possibly fit in a special issue. And remember, your reading here is framed, merely a snapshot of a continuously shifting landscape. The larger picture extends well beyond this frame, in time and place. It stretches into diasporas, exiles, prisons, and homelands occupied and imagined. It echoes in many languages, indigenous and imposed, and speaks in many tongues, native and adopted.

The purpose of this issue is not to alleviate existing anxieties towards the Middle East or invite new ones. It is not to celebrate or lament or explain or resolve or deny or establish anything about this region. If anything, it acknowledges the Middle East as a bind; might it begin to unravel in the mind, by some rearrangement, some association or unexpected juxtaposition, some turn of phrase, some wild metaphor.

For more from the Spring 2022 special issue of MQR, “Decades of Fire: New Writing from the Middle East and North Africa,” you can purchase the issue here.