May 15th commemorates the Palestinian Nakba of 1948 –Nakba is Arabic for catastrophe—in which over 800,000 Palestinians were displaced and near 600 villages destroyed as a result of the creation of the State of Israel. The following conversation among three Palestinian poets reflects on variations of identity, the aftermath of 1948, the Palestinian diaspora, distance, and the role of poetry as responsibility and resistance. This conversation was recently conducted, spanning the geographical distance between Dearborn, Michigan; Columbus, Ohio; and Gaza.

Noor Hindi is a Palestinian-American poet and reporter. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Magazine, Hobart, and Jubilat. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in American Poetry Review, Literary Hub, and the Adroit Journal. In 2021, Hindi received a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. Her debut collection of poems, Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. is forthcoming from Haymarket Books on May 31st, 2022. Hindi earned her BA and MFA in poetry from the University of Akron and currently lives in Dearborn, Michigan.

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet and librarian who was born in Gaza and spent his life there. He is founder of the Edward Said Public Library in Gaza and in 2019-2020, he was a Visiting Poet in the Department of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. Abu Toha is a columnist for Arrowsmith Press; his prose writings have appeared in The Nation and Literary Huband his poetry has been published in Poetry Magazine, Poem-a-Day, Banipal, Solstice, The Markaz Review, The New Arab, Peripheries, among others. His debut poetry collection, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, was published by City Lights in April 2022.

Sara Abou Rashed is a Palestinian American poet, storyteller and TEDx speaker. Her works appear in the anthology A Land With A People, 9-12 English Language Arts curriculum from McGraw Hill, and more recently, in ArabLit Quarterly and PoetryMagazine. In 2018, Sara launched her autobiographical one-woman show about immigration and finding home titled, A Map of Myself, which she has performed over 17 times across the US. Born in Syria, Sara graduated from Denison University and is currently pursuing her MFA at the University of Michigan.

Sara Abou Rashed: We’re three young Palestinian poets and I wanted to introduce you two to each other and through this conversation create a space where we can bond over all that we have in common and all that makes us unique, so let me begin with what does it mean for you to be a Palestinian poet, especially that the Palestinian identity has a spectrum to it and we all cover different variations. I was born in Syria as a refugee and lived in exile my entire life; Mosab, you’re originally from Yaffa but stranded in Gaza and was only recently allowed to leave, and Noor, as a Palestinian American, you have that duality from birth. Tell me about that.

Mosab Abu Toha: Being a Palestinian poet means that you have a duty to towards your people. Being able to speak a different language, a language that is spoken and understood worldwide makes it a duty for you to speak that language and to write using it on behalf of your people, because what’s seen on the news or the Internet is only what journalists were able to portray and capture with their cameras and pens. For me as a poet, it’s my responsibility to write about what hasn’t been captured, what has been happening inside the house. For example, a poem I wrote was about a family of six people, the parents and their four children, all under ten years old, massacred in one Israeli airstrike. So I wrote a poem about the shrapnel, not only taking their lives, but also running after their laughter before they were killed, killing the pronouns in their school books. It’s my duty and responsibility to speak about these events, because these people are not just numbers.

Abou Rashed: Mosab it’s very affirming to hear you talk about that sense of burden because when Palestinians write, it is always with stakes. We write seriously and that’s something we to have to do always. Noor, you talk about exactly that in your poem, “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying,’’ which went viral when it was published in Poetry.

Hindi: It truly is this urgency to capture what is not being captured, what is defiantly being ignored and silenced about the Palestinian experience by reporters and journalists, and it’s really disheartening to see especially now, we see the current contrast, for example, between the way that Ukrainian refugees and fighters are being depicted with so much dignity and warmth and humanity, while Palestinian freedom fighters are captured as terrorists and violent and their deaths are passive. Palestinian children die; they don’t get murdered, they just die. My relationship to writing was born out of a desire to not feel disconnected to Falasteen anymore. I always felt guilty growing up in the US because my dad felt guilty. He lived in Falasteen until he was 20, he was on the front lines and protested his whole life. When he married my mom and left, his relationship became one of guilt and he always wanted to go back. One foot here, one foot there. He hated his relationship to the US, never had white or American friends, didn’t learn the English language. He just stayed. He stayed mentally in Falasteen.

In my pursuit to understand him, I wanted to understand Falasteen from that point, and the more I learned about it, the more I understood his character and his seriousness, and his guilt, and the heaviness of growing up in a house with him, and the more I could understand myself, and understand that I live in this country because of the war, because of occupation. None of us are living outside of Falasteen voluntarily, I think.

Abou Rashed: Noor, what you said about your dad staying mentally in Falasteen, do you think that’s your father’s thing or do you think that’s a Palestinian thing?

Hindi: The concept of assimilation is colonial; it assumes that a person changes and forgets their other country and just sort of joins American culture. And then there’s the process of integration, which is that you integrate these two cultures, and that’s become the more politically correct term. My dad did neither of those. He just was not going to collaborate and be part of the US. I think that is the experience of a lot of people, but I’ve also met a lot of Falastinyye who seem to meld with the US, make friends, join their local mosque, and move forward. I think, for my dad, he felt this great duty and desire to be on the front lines fighting. He would watch the news and feel so sad. Even when growing up, when we felt any heartache, he would say, “You could be in Falasteen, you could be experiencing much worse.’’

Our griefs were always comparable to those in Falasteen. I think for him, it was really difficult to even validate his own emotions at any given point because he constantly lived in comparison.

Abou Rashed: Mosab, what do you think, is it an individual or collective experience to often be somewhere, because I know that you’re often somewhere else in your presence and in your writing?

Abu Toha: It’s uneasy for anyone to relocate to a very far place like America. For your father, Noor, I imagine the hardest part was that he was moved to America and unable to return to Palestine. It’s unlike other people who could move to work or to live permanently. But for us, and for our grandparents, we are forced to leave our country. For me as a Palestinian who has been born in a refugee camp in Gaza, I am unable to go to Yaffa, my grandfather’s hometown. I can’t even visit it, I can’t see my grandfather’s house, if it still exists.

I remember when I was in America for a year and a half at Harvard University, then later for my MFA (and I’m still unable to finish my MFA because I’m not allowed to leave Gaza to attend my visa interview at the American Embassy), I was thinking about Gaza very much to the extent that I was concerned about my shadow that I left on the street in Gaza… This feeling of intimacy not only with the people, but also with the things that many people don’t think about.This is something that is rarely considered, except if you are a Palestinian who cannot easily return to these places so you care about them more than others who can return.

For Palestinians, it’s very difficult to leave your country and difficult to return. Here in Gaza, we are under siege since 2007 and before that under occupation. Not only this but it’s very difficult to return to Gaza because of the border crossing closures. We only have two border crossing entries, one between Gaza and Egypt, and one between Gaza and Israel. So you are stuck, whether you are inside your country, or outside of it. This is why we must think not only about ourselves, not only about our family, but about our shadows, about our footsteps in the street.

Abou Rashed: You said something that will resonate with me for a long time, just wherever you are, you’re somewhere else.

Hindi: I think you really captured that Palestinian sense of stuckness and aloneness, no matter what, and this lack of access to something you badly desire and are denied. I love the sentiment of the shadow and the imagery of that is so beautiful.

Abu Toha: I sometimes feel very strange when I read what I’m writing. But you don’t have a choice, this is what you feel as a Palestinian, I mean, you are just over human. We are over human who don’t just have feelings toward people, but also toward a stone, a bathtub that’s buried under the ceiling of a destroyed house. These things could only be thought about if you are a person who has been under the threat of death all the time, whether you are inside your home, whether you are going to the supermarket, to buy diapers for your children, whether you are going downstairs to water the parsley, the fig tree, a drone could come up in the air to shoot everything. These are things you think about when you are a Palestinian.

You just live a crazy life here, and this is why you sometimes do not control what you are writing about.

Abou Rashed: I love the term over human—that there is a lot more to us, because something was taking away from us. It’s ironic, that loss gives us an abundance of feelings. It makes me think of something I recently realized which is being an outsider here in the US is about the ability to compare. I was recently driving between Ohio and Michigan, and that entire drive, I was comparing what I know here in the US vs. what I know in Syria, so we are never fully here, fully present. There is that realm of the imagination, that there’s something else, that I’m uprooted and can’t be grounded. Both of you alluded to that, Mosab, your reflection even went in a metaphysical realm of the shadows and leaving traces behind. Noor, I feel, you also carry something of your father’s, whatever he left behind.

What does that realm do for you, does it hinder you from living a fully present life, does it allow you to write, is it what makes you you? Does it allow us to breath? Is it liberating not to be fully present? Because then we can maybe access the consciousness of things that are inanimate, objects like Mosab talked about, rocks, bathtubs, even our grandparents’ histories.

Hindi: I really love that Mosab talks in poems. I think that this sense of closeness with death is what it is. I started writing and reporting because of this desire to document. I was born in Amman, and we came here when I was two. From a young age, there was always this constant, overwhelming sense of grief. But it’s a grief I can’t name because I ask myself, how can I feel grief about Falasteen, a place I’ve never been to? How can you grieve over something that you don’t have access to and haven’t been able to visit? My dad couldn’t go back because of his history fighting the occupation. It’s a strange situation of being in limbo, and created for me this urgency to document, because when Sidi died, I felt I lost a part of Falasteen. When Sitti dies and I watch her grow older, I know I’m going to be losing an entire country. and I cannot imagine my relationship with Falasteen outside of my father, because I, myself, don’t have a relationship to this country outside of him, and outside of Sitti being born 50 days before Nakba.

Who tells these stories after our families pass away? And how do we continue to preserve the culture and the language, and the desire to fight the occupation after their stories disappear, after there’s no longer Sitti to huddle us around after dinner, and tell us about Khalti disappearing during Nakba and them not finding her for a month. These wild, wild stories that almost became legends when I was growing up. So I think for me, it’s a lot of just grief, misplaced grief. Even as an adult, I would love to visit, to go with my father and still, I know it’s going to be different. He will be seeing his shadows as Mosab said, and I will be coming into this country for the first time, and have no relation to it other than my father’s stories and a desire to connect to the land.

Abou Rashed: Noor, I want to push back slightly and say it’s not quite true when you say you have no relationship to Falasteen outside of your father and grandmother. You have something, and even if we cannot name it, that is enough, that is relationship enough. It reminds me of a question I am asked when I keep writing these return poems, which is: what do you mean you want to return, you’ve never even been? Indeed, I’ve never been. I was born in Syria as a Palestinian refugee and never gained Syrian citizenship because of that right to return under UNRWA guidelines, so like you, my only access to my Palestine is living with my grandmother, who was three years old when the Nakba happened.

To me, there’s always that rupture in time. 1948 is the beginning and end. I keep telling my grandmother, who recently became an American citizen, “would you want to visit?” And she says, “I love Palestine as if it no longer exists,” and in her mind, it does not exist. The Palestine she knows does not exist. I’m always writing toward that, toward what she knew, toward my grandmother’s memory, I’m writing backwards, back to 1948, back to where it all stopped. In your own writing, what are you writing towards?

Abu Toha: I just wanted first to comment on what Noor said about her family. Unfortunately here in Palestine, when we talk about Palestine, we talk about the Gaza Strip, where I live, but there’s also the West Bank, and what now is called Israel, which began with occupation of cities like Yaffa, Haifa, Akka, Al-Naserah, and Safad in 1948.

So, unfortunately, the occupation is not only geographically distancing us and pushing us away from the origins of our grandparents, but we are also being generationally distanced. For example, I’ve never seen my grandfather in my life. He passed away before my father got married. So I am a generation away from my father and two from my grandfather, and then there’s me and there’s my son and in the future, my son’s son. We are always being generationally distanced from what we know about Palestine. Palestine to me is my grandfather.

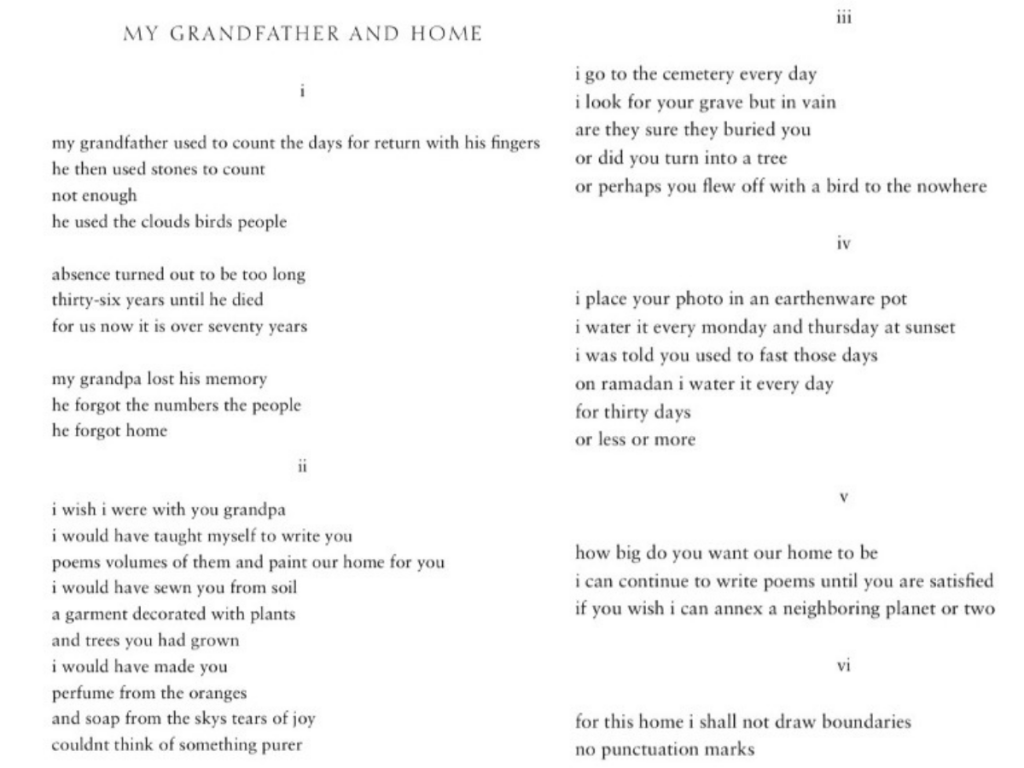

So, the longer we are living under occupation and away from our hometowns, the more this memory is likely to be weakened. What I’m writing about and the memory I’m trying to revive is what will keep the city of Yaffa and other cities near in our memories, as if they had recently been living in our minds, not only in our grandparents’. Maybe this generational distance is one reason while I’m always writing about my grandfather and Yaffa.

As for your question, I’m torn between two realities. I’m torn between the memory of my parents and my grandparents living in refugee camps, and because we are living under occupation and under the constant threat of escalation and war and destruction, I write also about these events. Some events I write about just a few hours after they happen, just like the family of six who were killed. I couldn’t control my feeling so I wrote it the way it is now in the book.

At the same time, war is not everything here. There is nature here, but this nature is mixed with the violence and the concern for our next generation. I was born in a refugee camp but my son wasn’t. He’s here in Gaza and I wonder what future awaits this child? It’s been about sixteen or seventeen years since the 2007 siege. What awaits this generation, what else there is to come for them? This is a big concern for many people here and I think the guilt that you are feeling of living abroad away from Palestine, I think this is something that many people wish to have, because they have been stranded here for a long, long, long time.

I left Gaza for the first time in 2019 at the age of twenty-seven, do you imagine someone being able to travel for the first time at the age of twenty-seven. This is the case for most young people here, that’s if they’re lucky enough to leave.

One last thing I’d add, I have a really strange wish, and I still haven’t achieved that, I want to imagine myself flying over my country. I’ve never had a flight over Palestine. I don’t know my country from above; I only know it on the ground. I just know Gazan buildings whether destroyed or intact from walking around, but I’ve never seen my country or the sea from above. That’s something we’re deprived of, because we don’t have an airport in Gaza or the West bank. Maybe this is something I’ll contemplate in future poems.

Hindi: I love that sense of flight and departure and migration that you illustrated, truly a beautiful image.

Abou Rashed: Mosab, when you say, I don’t know my country from above, from outside, it’s heartbreaking to say we don’t even know it from the inside first. I’ve read many of your writings where you talk about not being able to visit outside of the parameters of the Gaza Strip. Even Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem—anything that’s close by distance is unimaginable in actuality. Miles and kilometers and distance mean nothing in Palestine because of borders and authorities and checkpoints, so you could be thirty minutes away from something and it takes you thirty years to even get a permit to visit.

Abu Toha: This is very strange for us. For me, in Gaza, I’ve been under attack since I was born. I lost some friends of mine, and I got wounded in the 2008 and 2009 aggressions against Gaza. I was 16. I wrote about this in a poem. Usually when you are fighting someone, you can see them face to face.

But for me the people who are fighting me, the Israeli soldiers, whether in tanks or in jet planes, I don’t see them. I’ve never seen the face of a soldier. I wonder, who am I fighting? I’m fighting a ghost; they could see us, they have every means to see us. But I’ve never seen an Israeli soldier in my life; I’ve never touched them to see if they are human, or something else. This is very strange. I wonder why I can’t even do this?

Hindi: Thinking about the violence of not even being able to look your aggressor in the eyes.

Abou Rashed: Sometimes there’s a satisfaction in knowing that. You think about children bullying each other, maybe there’s a size difference, they can see that, they can understand that. But how do you understand systematic occupation? Land theft, erasure, disposition? Those are abstracts; we live abstracts.

Abu Toha: Even this aggressor doesn’t see us as a human being, they see us from afar as target dots. They see and do not see us. They do not know what we are doing now, what we are reading about and writing about. They do not know that we have mouths to laugh and to smile. They do not see us when we play football. They didn’t see the before children from the Bakker family, who were killed on the beach of Gaza in 2014. They were playing soccer. They just saw that these are people who might grow up and become threats in the future. Maybe this is the only justification they have in their minds.

Hindi: You think about the violence that’s created when someone is operating a drone like they’re playing a video game, and then the violence of the sound of that drone in a Gazan’s everyday life and what that type of terror does to your senses. Something we’re primarily talking about in this conversation seems to be distance: distance from one’s own country, from one’s ability to access other countries, distance from oppressed to oppressor, distance between generations, between geographical locations.

Abou Rashed: Noor, I’m tempted to ask you from where you sit in the world, what do you see? Mosab talks about almost wishing to see a solider or some human configuration of the occupation? What do you see when you write, when you think of Palestine?

Hindi: When I think of Palestine, I try to think of joy sometimes, but often I think of grief. It does feel like a disservice to talk about Falasteen only in terms of grief. Mosab is talking about playing soccer on the beach, of having dinner with family during Ramadan, of walking through the streets, of hugging your child, of having a child, of going to get diapers—all of those every day mechanisms that make up our lives. It doesn’t feel like a service to Falastinyye to only capture us in that grief.

But when I’m writing about Falasteen, I’m thinking about my connection to my family members, about the tongue a lot. I’ve lost a lot of language. My dad still has his dialect, we make fun of him and his old “cha.’’ I talk like that sometimes and he laughs at me. I’ve been feeling weird about that, even about wearing my kuffiyye around because nothing ever feels like enough resistance. And the only way I know how to resist, like Mosab said, is with writing about everything that reporters are missing, everything undocumented, everything that colonizers who are so swift to write our stories are leaving out. I am a poet and a reporter because I grew up in that erasure. We never read about Falasteen in my history textbooks. I didn’t understand when I was growing up why the place on the map my dad was pointing to and naming one thing, was named Israel.

Dad always had Al-Jazeera on, that was in the background of my life. A constant fight between him and my mom, who’d say, “Please turn down the news, I can’t listen to this anymore.” When something major happened like 2008, and I was old enough to read American accounts of it and to understand what my dad was saying, I found these two narratives would contradict each other so much. It was on me to stitch truth or a semblance of the truth. When I started my job reporting, it became even clearer who gets to write history. Writing poems feels like the most empowering way to write one’s own history and take something back from colonizers.

Abou Rashed: There’s something that’s recently been in the light, which is Palestinian Futurism as a concept, but also a literary movement that’s trying to imagine a future and it’s taking after Afro-Futurism, asking us what else could there be—what joy, what celebration? What would it look like to look and write forward instead of backward? Do you feel that you engage with that? Or, that it is possible to, given that we’re so fraught in the present moment that it’s hard to be anywhere else. Mosab, just a few days ago around Easter and Passover, Gaza was under attack and I didn’t even know if my friends, if people like you, would still be there, if this interview could’ve still happened. Back to distance, the fact that death could face us in a minute, that feels too close for me to imagine a future as much as I would like to.

Abu Toha: A future…is it a positive or a negative future? It depends on the experience of the writer of the text and the form, whether a poem or a narrative piece, etc. If someone is going to write something positive about the future, they need to experience something positive. They need to get out of the miserable place they’ve been in for a long time.

I used to think Gaza is huge until I left it. It’s about 140 square miles, comparatively, just a tiny place and takes only an hour to cross from north to south. But when I lived in America and traveled from Syracuse to New York City, it took us about 5 hours in the car and we were still in the same country, same state. I was shocked. So the occupation is not only occupying our land, but also our minds and our perceptions because it’s forbidding us from traveling to experience the world.

Imagine how big planet Earth is! Our struggle is not only about death, it’s about taking away from us our ability to imagine. That’s why imagining a future depends on experience, whether I’ve been able to see things for myself. The words snow and squirrel and deer entered my dictionary only when I was in the US. I never used them before then and only after seeing them could make up stories about them to my children.

People talk about the pandemic; it’s like Covid-19 has been here since before we were born. It shouldn’t be a luxury to travel, Palestinian grandparents rarely see their grandchildren…I was able to see my paternal aunt for the first time in twenty years only when I left Gaza. What future do you want us to speak about when we are unable to experience the now of other landscapes, other languages, even other dialects in different parts of Palestine? What future, when I’ve never been able to go to the West Bank or Jerusalem which are designated as “Palestinian Territories”?

Hindi: Mosab, you’re speaking about the scope of one’s imagination, and the ability to imagine when one is under siege. I’m hearing you as a fellow Palestinian talk about that and then I’m thinking about Elon Musk’s ability to imagine that he can visit other planets. Look at the contrast and the way the mind expands based on environment.

I don’t know how to feel about Palestinian Futurism, because on one level, I believe that one needs to imagine a future in order to have something to fight for and I believe that they’ve stolen our land, they’ve stolen our plants, they’re stealing our children. What we have for ourselves is our ability to tell stories and our imagination—this is something they can never steal from us. I want Palestinians to stand in that with full ownership.

But, on the other hand, I want to recognize the privilege of being able to imagine a future when I’m not seeing death around me every day, I’m not facing checkpoints when I’m traveling. I can drive fifteen hours to Texas and come back and it’ll still feel small, the world feels small because I can move in it.

Abou Rashed: This is why it’s so important to have writers, poets like you two who raise these questions, who say we want liberation more than anything, we want a future, but we want a liberated present.

We want to live not just for the future; it’s a very Palestinian and Arab thing we do, we endure the suffering and hardship of now in the hopes something better comes later.

Hindi: What is that on the tip of our tongue? Inshallah, inshallah.

Abou Rashed: Exactly—even our language, the way we go about our lives, about making plans.

Hindi: We need hope, too. Mosab, I’m sure you imagine a future for your son to some degree, that you tell him these stories because he will grow up and learn from them. That is a kind of hope, I would think.

Abu Toha: My challenge and hope for the future now that my first poetry collection is out, is to pen new poems with less of a bleak atmosphere. I just don’t want to continue writing about shrapnel, about bombs and ruins. I want to see something positive, but I’m not sure if we are allowed to have that here in Gaza and as Palestinians in general. We are disallowed from thinking hopefully.

Abou Rashed: I’ve always envied people who can write about silly things, things that don’t matter, poems that don’t matter. I know it perplexes a lot of people when I say that, and I’m sorry for it, surely to them it matters, but in the grand scheme of things, I’m looking for that urgency, that life-or-death, that inescapable duty and responsibility we talked about in the first question.

I want to ask you two, with your first books coming out, do you feel that you had to write through the shrapnel and grief to come out on the other side? Or do you feel like it’s a shadow that’s cast on all of your writing, all of your life, especially with the US in mind? You’re both writing and publishing in English. There’s censorship and literary erasure happening on some level, people who in response to your writing will say, “How dare you!” and those who commend you for saying bravely what you say.

Abu Toha: Two big reasons why writing is essential for me is that I feel compelled to write about the lives of those who died under the rubble of their houses. I want to write about their life, about what they were doing before their lives were taken from them. So this is what I’m writing for and because of others. Sometimes I write to put all the negative and hideous creatures and images that are stored in my mind –– The noises of drones, the buzzing, the explosions, the light flickering after them –– I put all these images down to get rid of them. These images recur in my dreams, they’re stored in my subconscious…

Something really strange happened: one time I went to sleep and dreamt that a sheet of paper was burning. I woke up to check on that same paper, and discovered that the last word I wrote was “bomb” and I hadn’t ended the sentence with a full stop.

Abou Rashed: So it’s only natural it exploded!

Hindi: This image makes me think of one’s ability or inability to rest. The speaker in this poem has literally slept next to a bomb which feels very resonant of the Gazan experience. Sara, it’s a great question what you asked. Unfortunately, because the poetry publishing world here is primarily dominated by white Americans, with the words we write on the page, there is this thirst for our blood by white readerships, and this desire to sell, and this desire to feel that it is an act of social justice to simply read works by people of color, by Falastinyye, by refugees, and that’s not right. The words should motivate you to help, to vote and to think about where your tax dollars are going, reading or acquiring should not be where you start and stop.

That being said, on the one hand, there is a desire for us to write and to protest and to change the narrative of our people. On the other hand, I am writing my second book of poems right now and there’s a lot less Falasteen in it, a lot less terror in the poems. They are a little sillier, there is some humor. I want to see a world where every Palestinian can write silly and funny and joyfully.

That is the future I’d love for us to have but also I feel that I wouldn’t be able to get away with this second book without the first book doing the work. Yes, I felt pressure from the industry, but it is also a duty and we carry that responsibility. Everything is political; we can’t write about our past without thinking about the stolen native land we’re on. None of these things can be separated.

Abou Rashed: Are you afraid of the consequences of publishing your first books, both deeply Palestinian? And are you also afraid of your poetry being dismissed or simply labeled as political poetry? I’ve avoided calling your works that even though I strongly believe it is, because I don’t want to do the categorization that is often done to us because being Palestinian is itself political. I hear, “Oh, you write political poetry, I’m not into that’’ when in reality, no, we don’t write just that; we write about everything.

Abu Toha: I think our poetry is humanistic, and to write humanely you have to engage fully with your life. Our lives have been smeared by political schemes, so we cannot escape it. When you write something, you have an aim behind it. This is politics, the work of persuasion. Even a salesman is a man of politics.

But when it comes to Palestine, it’s clear you are telling the story of your grandparents, about the loss that’s been suffered by your community. If they call this politics, so what? This is our life, we’re not adding anything to it. We cannot just talk about the sun and how hot, or how far, or, or.

Abou Rashed: But I do hope that one day we can write just that, about the sun and how hot and far and that being enough!

Abu Toha: Yes, I hope the occupation ends so we can write about that and about the fish lurking in the cafeteria to drink coffee with me. I’d really like to write that.

Abou Rashed: About flowers, right, Noor?

Hindi: I get very annoyed about the word political and the way that it’s used, because I think that when you are marginalized or has faced violence, the distance between you and politics is so close. When you live with privilege and don’t think about violence, the distance between you and what is political, is far.

It’s very frustrating, because you can’t be marginalized and live anywhere in the United States, for example, without there being connection to politics. I was a housing reporter and saw the way our neighborhoods are zoned, the way we are able to afford or not afford rent or buying a home, our transportation to cities, our ability to live in places with clean air away from manufacturing, there is no choice. Even the toothpaste we brush our teeth with, the chicken we cook. There is no distance between us and politics, yet, white people have this amazing ability to separate the two.

Abou Rashed: There’s a lot we’ve talked about and a lot more waiting to be talked about still. Before we conclude, I want to touch on gender and how that shapes our consciousness, being a Palestinian man vs. woman.

Abu Toha: I cannot answer this question, because I cannot say something about myself without being the other. Maybe you can ask the oppressor about the feeling of the oppressed, but they’ll have no answer. I cannot tell you how I feel as a as a male Palestinian, because I’ve never been anything else. Palestinian men and women both have been very integral to the resistance. There are many Palestinian women in the diaspora or even in Palestine, who are writing about issues that concern their communities and themselves as mothers, sisters, daughters. To me a female or male Palestinian have the same values.

Hindi: I’m going to push back here, because in my head the fight for a free Palestine is inextricably linked and rooted with the fight for women’s justice, the rights of queer people, the rights of darker-skinned Palestinians. Freedom for Palestine means freedom for all and freedom from capitalism. Women’s rights is something I write a lot about in my book, as well as sexuality and the ability for women to feel desire; how they are desired, how they are looked at, and how they’re looked upon.

Again, there’s much more to it but I’ll leave that open-ended. And Mosab, it has been amazing meeting you. I’m so excited to interact and get to know you more. Thank you, Sara, for connecting us.

Abu Toha: Thank you, Sara, and thank you, Noor. It’s been a great, insightful conversation with the both of you. I hope we will have many more on issues that concern us as human beings and as Palestinians.