Thirty years ago, I began a research project called “Contemporary Russian Poetry and Its Relationship to Historical Change,” thanks to a fellowship from the Watson Foundation. During the tumult of post-Soviet economic “shock therapy,” I lived in Russia, interviewing and translating leading contemporary Russian poets, trying to understand how poets were understanding their changing role in society. I’ve continued to interview Russian and Russian language poets in the Putin era. This interview with Maria Malinovskaya explores the poet’s background in poetry, her relationship to documentary poetics, and political protest in her native Belarus. Malinovskaya is a poet, translator, and founder and editor-in-chief of RADAR international poetry magazine. She is an author of two books: a documentary poetry project and collection Kaimaniya (2020), based on the speech of people suffering from mental disorders, and The Movement of Hidden Colonies (2020). Malinovskaya’s poetry has been published in numerous anthologies and magazines and translated into many languages. Malinovskaya’s poem, “white-red-white flag,” based on the events relating to the Belarusian protests of 2020, won one of the main awards for poetry written in Russian language, the Poesia Prize (2021).

Philip Metres (PM): If this isn’t too boring, let’s start from the beginning. When did you start writing poetry and why?

Maria Malinovskaya (MM): I started writing poetry at the age of 11, but I consider ten the starting point. When I was ten, an event happened to me that turned my perception of myself and the world. I couldn’t tell anyone about it, because I didn’t know how. But I felt that it was necessary to speak—not directly, not to someone specific. A language was needed, and that language turned out to be poetry.

PM: What happened when you were ten?

MM: I’ve never talked about it in interviews or in public, but clearly the time has come to talk about it, because the event defined and continues to define me as a poet. At age ten, I felt a connection to someone who died before I was born. He wasn’t a relative, wasn’t a friend of our family, and it seemed all the more inexplicable. This gave me a powerful push to rethink myself and the world, this strong pain and equally strong joy. A feeling of continuous wonder in real time. A wonder that’s impossible, completely impossible to talk about—because you don’t know how to talk, and because you know that you will not be understood or believed. But the need to speak was enormous—to speak directly, not only about the inexplicable, but also with the inexplicable. That’s probably how people come to poetry.

PM: Why do you keep writing?

MM: Because I learned a language in which you can speak with everything. It needs to be learned and at the same time it needs to be created on the go, because everything is constantly changing. You cannot say about today exactly what you said about yesterday; otherwise you will not express the main thing. Nor do I see much sense in talking about the present day as people already talk about it. That is, every time you open this world through language anew, it is a continuous process that requires the constant transformation of poetics and the search for new forms.

I also keep writing because the same need to talk about the inexplicable and with the inexplicable that I had as a child persists to this day. It defined every phase of my human and creative growth, every form of writing, and every change of writing form. As a numerical function tends to infinity, so did the language in my poetry strive. To express the inexpressible, to express something unutterable, start talking, beyond language, beyond material existence, in the “subtle world” of words and their meanings—that’s what I always expected from poetry, my own and others’.

PM: What is your goal when you write?

MM: It depends on what I’m writing. For me, language poems are about exploring the boundaries of the self and the other through language. Narrative poems are the most reliable way to convey a certain experience (for example, my texts “white-red-white flag” and “where are your political prisoners,” about the political protests in Belarus). Documentary poetry is an opportunity to give a voice to those who are deprived of it due to social stigma, the threat of legal persecution, or other circumstances (for example, my documentary poetry cycle “Kaimaniya,” based on the speech of people suffering from mental disorders).

My new poetry cycle “A Time of Its Own,” based on the testimony of a man who survived the civil war in the Ivory Coast, is an attempt to go beyond documentary poetry. In it, verbatim turns into a lyrical utterance, the voice of another connects with mine; he is no longer a nameless source of information, but a subject who understands his role in the context of a work of art and is able to disagree with it—which I also recorded in the texts.

documentary art is wicked i don’t want any documentary art when the helicopter arrived and took us from the roof of our house we couldn’t even take some footwear my children stood in the airport barefoot and some jerk came up a modern photographer and started taking pictures of them my wife asked me what he was doing it hurt her I went up and asked what are you doing bastard? why are you shooting my children barefoot? he said it was important to show suffering so that the world would know and blah-blah-blah i said ok bastard i don’t want you to show my suffering how he fretted that photographer began explaining that this is documentary art i told him i had lost everything the rebels burned my house down we don’t even have our passports and you call this art? delete everything you’ve shot and don’t come near us again i don’t show my suffering it’s just self-respect and i will never allow others to show it we went north to my mom’s native village we met a neighbor who remembered me at the passport office they asked me do you swear that’s your name? they asked my mom do you swear this is your son? asked the neighbor do you confirm this? then sign here and that’s how i got my passport that’s when i really fell in love with my country but obtaining the passport i immediately flew back because i needed to make money and not make sense of the trauma or anything else it’s life and there’s nothing special about it Translated by Sergei Tseytlin

PM: Which poets and writers have had the greatest influence on you?

MM: The most powerful literary influence was for me at the age of 13-14, Arthur Rimbaud, namely his prose—Illuminations and A Season in Hell. But it all started with Agnieszka Holland’s film Total Eclipse, about him and Verlaine. These were some completely different poets of the 19th century than those dreary stencil uncles, obsessed with an unearthly love for the same dreary aunts that we were told about at school. After the movie, I asked one of my friends to download Rimbaud’s prose from the Internet. (I didn’t have the Internet at that time.) And when I read Illuminations, that sealed the deal. That was real.

Rimbaud was followed by other “Damned poets” (poètes maudits) and in general all French literature from the end of the 19th century to the present day. When I was 17, I was struck by Marcel Proust. I read all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time in one breath, and then as many more volumes of research about them. Another great passion of the time was Thomas Mann. Of the Russian writers, perhaps, Dostoevsky and Merezhkovsky. At the same age (17-18 years), I discovered Camus. I’ve read The Stranger countless times, and all my friends have watched Visconti’s movie with me. This passion lasted perhaps longer than the others, perhaps because Camus wrote about Algeria, and the Arab countries—their landscapes and architecture have always attracted me with amazing force—both in literature and in movies.

When I was a student, I discovered Kolonna Publications and began to read everything they published in Russian translations, especially in the “Vessel of Iniquity” series: Pierre Guyotat, Tony Duvert, Gabrielle Wittkop, Herve Guibert and, of course, Francois Augieras, who again has everything as I love: Algeria, ecstasy of being, and homosexual love.

By the way, taking a break from this extremely pleasant topic, I want to note that, a few years ago, when I had already written “Kaimaniya” and “You are people. I’m not” and thought about how to build the next documentary text, I was influenced by your Sand Opera. This is probably my favorite documentary poem.

PM: I don’t know much about Belarus, so forgive me if this is a naïve question: why do you write in Russian, the language of Russian empire?

MM: I write in the language I have been speaking since birth, which my parents speak, and my grandparents spoke. Belarus has two official languages. The majority of the population speaks Russian, but everybody knows Belarusian. I am fluent in Belarusian and love it very much. Sometimes I translate from it into Russian. This is an incredibly melodious, expressive language in which you can hear the passage of time.

PM: When I began this project of interviews, it was the epoch of Yeltsin. There was excitement, and also a great fear—fear of the unknown, fear of freedom, fear of “wild capitalism.” I remember how many people suffered from the historical and economic changes—the loss of economic security, as well as the loss of ideological beliefs. What was life like for you in the 1990s? How is it different today, in Belarus?

MM: I was a child in the ’90’s, and life seemed quite beautiful to me then. But now, years later, I understand how difficult and unstable it was. Many films were made about the ’90’s. Some people hoped for changes, some people got rich quickly and illegally, some people built careers. Older friends told me about their “adventures” in the ’90’s: all in the best traditions of action movies with harassment, setups, “honest cops” and “real boys.” One of the narrators is now, for example, quietly working at the Academy of Sciences, and only his black Beemer with its bandit squint of headlights reminds of the “glorious past.”

By the way, I was born with the white-red-white flag, which was replaced with the current national flag in 1995 and now, along with the coat of arms “Pahonia,” is a symbol of national protests. The current President has been in power since the year of my birth—that is, I have not seen another, non-Lukashenko Belarus, and I did not even think of it as a child. The first years of his reign were generally encouraging. No one could have thought that they would be followed by stagnation, and after stagnation—terror.

PM: Could you explain the context of your two poems about the protests?

MM: On August 9, 2020, the next presidential election was held in Belarus, according to the official results of which the current president received more than 80% of the vote. This was an insult (hardly the first one) to the entire nation who supported another candidate—Svetlana Tikhanovskaya. Regular protests began in Minsk and other cities of Belarus. However, despite the clearly marked peaceful nature of all actions, they were severely suppressed by the security forces: people were snatched from the crowd (and very often by unidentified plainclothes police), severely beaten on the spot and in police stations. Thousands of people have been tortured, and some have died. However, this policy of the authorities, focused on total intimidation, only united the nation.

I was born in Belarus, but I have been living in Moscow since I was a student. I come to Gomel only on graduate school business and to visit my parents. In 2020, my arrival coincided with the beginning of pre-election unrest. (The people began to actively express their position in relation to the current government long before the elections.) When I returned to Belarus, I had a lot of questions. I did not understand much about the political situation, and at some point I called my best friend—the same friend from the poem “white-red-white flag.” The conversation that followed formed the basis of this poem and forced me to review the entire history of relations with this person in the context of his and my attitude to what is happening in our country.

the white-red-white flag on your profile photo i’ve seen for a long time but hadn’t noticed until now and today when you called and yelled or rather when i called and you yelled all you provocateurs call and ask questions (but i have no one elsein this countryother than you) i hung up and stared for a long time at the red-white-red flag i haven’t really seen that my best friend is what’s called a jingoist but you yelled find me a job there in Moscow for a hundred thou i won’t go for less well if it includes accommodation fifty thou will do and i saw you’re not a jingo hardly even speak Belarusian you’re just lost weak anonymized like everyone elsei thoughti knew because this is the first time i’ve ever heard how you yell at me fucking sheep stupid bitch go back to your moscow what are you doing here you didn’t yellstupid fucking bitcheven then in my 15 in your 32 you spoke in your always even voice you’re too smart a girl for someone like me we’ll get married you’ll want to keep growing and i don’t want to you will keep growing i’ll get jealous think you have someone else you’ll get offended and you’ll have someone else you didn’t yellstupid fucking bitcheven when you didn’t have time to tell me you got divorced you just kept quiet and listened as i said that i met someone and my family hates him that’s why i’m calling i don’t have anyone else in this country but you you didn’t yellstupid fucking bitcheven when i ran away from home you helped me run away from home passed me money in a paper envelope for a train ticket and the hydrofoil you didn’t yell when i was in the accident you came to tow the car but i yelled because we lost it twice in the middle of the road and my father was in it you calmed me down drove around the block hooked the cable to the car again calmed my father and we continued on our way so when did i become a fucking stupid bitch if you didn’t fuck me if you were afraid your whole life i’d get fucked? when you taught me how to kiss? when you taught me how to cut tomatoes and then in your little room on a sheet stuck with little seeds of these and other tomatoes we watched “the green mile”? i stared at the screen and couldn’t follow the plot because i was nuts we were almost like adults and then you drove me home under an epileptic sky and the wipers ofourthe battered mazda you called by my name bent and gnashed under the pressure of water and we sang in two voices “riders on the storm” was that when i was a finished? or when we fought turning in circles around the park? heavily monotonously as all my fights with you were like turning over stones under water and then my stiletto flew off and you carried me all the way home in your arms or on the old riverbed? you lay out on the blanket bread sausage boiled eggs and i cut my foot on the other side and swimming back i thought the foot is going numb must have been a snake but didn’t say anything all night until you saw blood and wrapped it in plantain and carried me all the way home in your arms or when i rang up the hospitals and found out which you came to your bed was facing away from the entrance and i could not get enough air to call took the three longest steps of my life and you looked up or when a white-red-white flag appeared on your profile photo? and when did it appear, by the way? maybe it was always there and there’s no contradiction in that you’re a best friend to me and i’m a fucking bitch to you sometimes it happens that way or maybe that’s the point that your attitude toward me is alive dynamic but i’m like this inhibited country i didn’t notice how i became finished didn’t notice how you stopped being my best friend i just feel reassured thinking about you in that way so that i don’t have to think at all fucked up muscovites know everything better than anyone teach you how to live she will go to the protests yes one blow with a baton is enough for you just go to the city look out the window and write truth to your left-wing pederasts open the entrance so people can hide and your fucking contribution to the revolution will be enough __ i’m fifteen we’re walking down a dirt road you pick from a tree a little white flower and put it in my hair my happiness is probably out of proportion to the act but at the moment it seems there’s nothing more beautiful i still think nothing has been more beautiful and you say how little you need and i don’t understand these words

My second revolutionary poem (“where are your political prisoners”) was written after I myself actively joined the protest activities in my hometown of Gomel. It is especially important for me that what is described in this poem did not take place in Minsk. Events in the capital are always widely covered in the media, but the display of popular unrest in the province can reveal their non-obvious sides, small nuances that are invisible on a large-scale canvas—specific people, ordinary Belarusians who took to the streets of their city for freedom, despite all the threats of the authorities. My best friend is not mentioned in this poem, although he was at every peaceful march, and then, like many other Gomel residents, lost his job because of this. But in this text, it was important for me to show not a personal story, but a general one, and not the story of people close to me, but the story of strangers who became close.

“where are your political prisoners? girl where are your political prisoners?” “in prisons!” tatiana shouts for me “in prisons!” nadezhda shouts for me don’t answer him he’s a provocateur check out see he’s bothered “hey girl why did you come here?” “provocateur how much did they pay you?” tatiana moves closer to me nadezhda moves closer to me and we start chanting “how much does a conscience cost?” “how much does a conscience cost?” he stands right in front of me huge and sweaty like a nostril pie nose pink cheeks pink hands pink blind plastic of black glasses iron stick his breath separating us and the wind waving a banner “freedom for political prisoners” in the hands of nadezhda in the hands of me in the hands of tatiana in the hands of vladimir i’m not breathing i think i’m alone i think i’m not alone these people are with me because i’m with them we’re not going we’re standing at a fenced-off square there is an imitation of a fair shabby hastily set-up tents two mummers shout into a microphone a couple of old women are walking hunched between empty counters vans empty of bodies yawn in front of the theater the organizers are sitting in the shade alone looking in front of them drinking water we’re waiting for the others the procession has stretched out “you fool, drop that stuff!” he swings i dodge the stick hits the banner hits the asphalt “for fuck sakes!” he leaves “where are your political prisoners girl? who are your political prisoners?” i saw them three years ago in photos at the Belarusian House of Human Rights in Lithuania and someone told me “this is a musician he was detained when he sang in the underpass he’s still in prison” and next a photo of the musician’s wife with their daughter in her arms “and that one is an artist” on the evening of the first day i went to the kitchen of the house of human rights and said hello to those who were there “Whit urr ye sayin?” those who were there answered “How come urr ye speaking Russian?” i told them ah’m sorry and didn’t speak there at all anymore i didn’t go into the kitchen when someone was there and i wouldn’t take a free cookie in the human rights house where i was denied the right to speakin in my language i walked alone through the streets cafes galleries of vilnius spoke only english and at night when everyone was asleep i went down the wide staircase of the house of human rights turned on the lights on every flight of stairs and looked at the portraits of political prisoners with distrust on those who demand freedom for them on those who do not recognize freedom for me “free-dom!” “free-dom!” “free-dom!” i shout tatiana shouts nadezhda shouts everyone thinks for themselves at the crossroads there are undercover agents and sectarians undercover agents in black masks and black glasses look for shadows cling to the walls sectarians stick out from behind corners hold up cardboard signs with the words “go to hell, evil ones!” don’t dare to join the procession two in the back “i voted for Lukashenko” “i did too, but how can we not come out for freedom?” “feed them!” “feed them!” the children scream “what is that?” asks nadezhda we changed it to “feed them” explains Tatyana and we together with children shout “feed them!” the kids are happy the whole street is shouting “feed them!” that seems to be truly about freedom three meters ahead correspondents and kin move backwards capturing it on camera nearby, a long-haired man on a bike coordinates the procession and then asks wait wait let’s wait a little “peace! labor! may!” a happy grandpa shouts “make love not war!” a hippie with a white-red-white flag on his back shouts “happy birthday freddie!” i shout “i’m sick of it!” someone’s dad shouts and shoves the camera back into the crowd “as long as we’re united, we won’t be defeated!” “the tribunal! the tribunal!” “freedom!”

PM: When I started collecting interviews of Russian poets in 1992, “creative writing” didn’t exist, but poetry still had cultural value. Now, it seems that poetry does not resonate with the masses, but has its own institutions, as in the United States. On the one hand, it seems that in Russia poetry does not play a big role in society, like in the United States. On the other hand, if you take the performance of Pussy Riot in the cathedral that led to their arrests and imprisonment, it turns out that poetry is stronger than ever. What do you think?

MM: Pussy Riot—it’s all actionism [the art movement], not poetry. In addition, the wider public was attracted by the loud consequences of the incident, and not its artistic meaning. If it were not for the prison sentence of the participants of the speech, much fewer people would have learned about their activities, which are significant and relevant for contemporary Russia, but remain beyond the interest of the general public. Modern poetic writing is, again, a language that needs to be mastered before you can read it and enjoy it. It is only in times of social upheaval, such as in Belarus today, that the poet and the reader begin to speak the same language. The reader leaves the comfort zone, begins to comprehend and transform the world around them, and the poet testifies to this. I saw people’s reactions to my poem “white-red-white flag,” written about a friend involved in protest activities. Even representatives of the “traditional camp” of modern poetry wrote that this text was close to them. All the battles over form and language have faded into the background. This is probably, as you said in the question, evidence that “poetry is strong today”—but only when society ceases to be passive.

PM: How do you view, from your point of view, the contemporary situation between Russia and Ukraine?

MM: The current situation between Russia and Ukraine is extremely painful for Russians as well. Nobody wants war. There are those who believe in its inevitability, but no one wants it. Except perhaps for some populations with a minimal degree of awareness. I have been working on the Russian Monologues project since May, talking to all sorts of people who live here about what is happening and writing down their responses in the form of documentary poems. From this literary and social project, another parallel project began to be born—in the field of visual poetry. I highlight the most typical words and phrases for the current situation and place them in the space of a square divided into black and white sectors. Thus, the “naked” language of the war comes to the fore—outside the text. It becomes clear how new meanings arise and old ones change. And all units of speech are opposed to each other. Working on these projects as a documentary poet, I try to remain open to a variety of positions, although as a person and a pacifist, this is sometimes difficult for me. But I think that this is the only way to show, without bias, what is happening—without being silent about anything, without conjecturing anything, giving voice to people or even to the language itself.

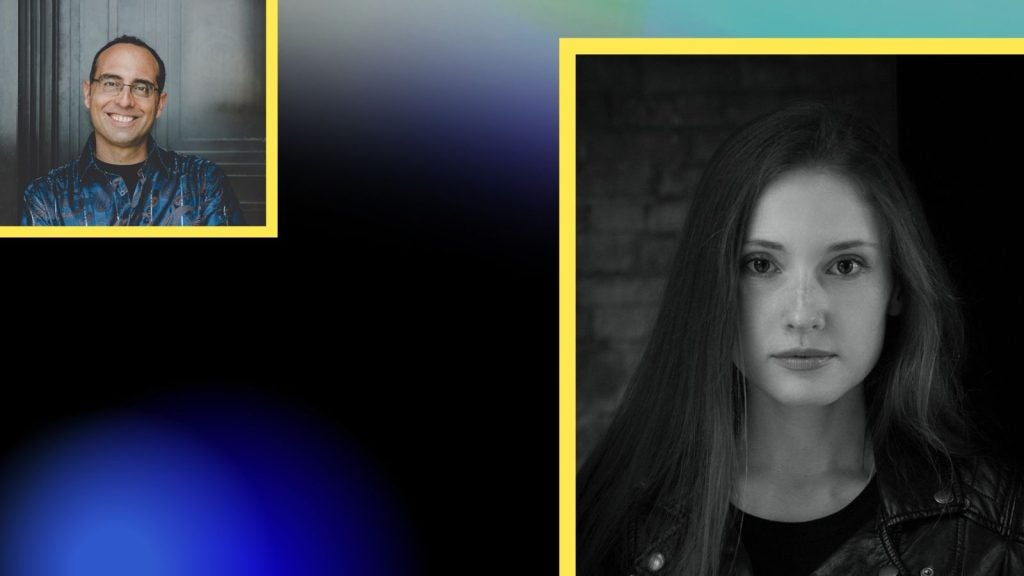

Editor’s Note: The photo of Maria Malinovskaya (on the right in the cover image) was taken by photographer Dirk Skiba. Unless otherwise noted, (for example, the lines translated by Sergei Tseytlin) the above poems as well as this interview were translated by Philip Metres.