–John Foster

Ann Arbor winters have a talent for keeping students indoors, but last week Thursday at six o’clock, already dark in the thick of January, and with a nuisance of a cold, I wrapped up in a  scarf and braved the evening air to attend Thursday’s roundtable panel on “Promoting Translated Literature in the US.”

scarf and braved the evening air to attend Thursday’s roundtable panel on “Promoting Translated Literature in the US.”

As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, writing a thesis on Walter Benjamin and theories of translation, I couldn’t have picked a better time or university to pursue my interests.

The roundtable is merely one facet of a sustained initiative at Michigan towards promoting translation as professional practice and subject of academic study that includes yearly translate-a-thons, and the acquisition and re-launching of translation journal, Absinthe.

Thrilling best describes the developments in translation spearheaded by the Comparative Literature department that have subsequently evolved to engage disciplines across the university.

The department of Political Science’s participation as co-host of Thursday’s event stands as a signature case-in-point.

Clearly, research in translation studies such as mine has profited by the increasing emphasis on the legitimacy of translation study and thoughtful discussion. Moreover, as the panel aptly demonstrated last night, the relevance of translation extends beyond academic inquiries and pertains to many of the most pressing questions we face as Americans in the twenty-first century.

What was particularly striking about the roundtable, and what distinguished it from similar events, was the variety of professional and cultural backgrounds found in our speakers, and the fact that only one of the three is working in academia.

Such an inclusive gesture marked the importance of bridging divides between academic and professional, as well as national and cultural, communities.

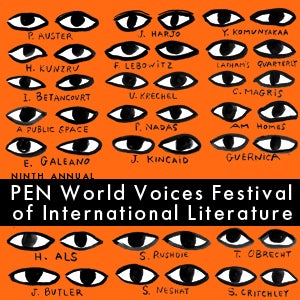

Each of the speakers brought a unique perspective and voice that informed the conversation: Esther Allen, co-founder of the PEN World Voices Festival and professor at Baruch College; Laurence Marie, the cultural attaché to the French Embassy in the United States; and Jadranka Vrsalovic-Carevic, the director of the Institut Ramon Lull’s New York Office.

The unifying thread of the speaker’s careers is their work in promoting awareness and practice of translation in the United States.

The conversation commenced when host and Comparative Literature doctoral student, Etienne Charriere, asked the speakers how they conceived of their role as “promoters.” In reply, Laurence Marie quickly clarified that her role should not be misconstrued as a means of disseminating some idea of French superiority in literature.

Marie’s response supplies a useful framing for the ensuing discussion and indeed for a growing number of pervasive and important questions that are being raised in twenty-first century America:

How does language, and its use, influence cross-cultural interactions in a time of unprecedented global connectivity? Can translation of foreign literature into English enable multicultural flourishing, or might it efface the subjective experience of alterity? How can the educational system of America equip its citizens to interact effectively with other cultures and encourage cultural and linguistic egalitarianism within its borders?

Perhaps the most salient observation was Esther Allen’s remark that English literature and culture has reached such a degree of global media dominance that it requires no promotion; even as Vrsalovic-Carevic’s work at the Institut Ramon Lull struggles to establish visibility for Catalan music, dance, food, language, and general culture, as well as literature.

No one should expect translation studies or practice to be capable of addressing the proliferation of American popular culture. Nonetheless, translation is uniquely situated to have influence on how, and to what degree, foreign literature and culture enters America based on translation’s relationship to education, including, but not limited to, foreign language learning, literacy, and cultural acumen.

A problem arises, however, when we consider ways of making the foreign attractive to students. To be sure, the allure of otherness can be a point of entry into reading practices for developing students; and translation can empower students to feel a sense of agency in foreign language learning—in France, for instance, Thème et Version (translation into and out of the target language) is common practice in foreign language classrooms.

But we risk exoticization when cultural literacy becomes an appealing commodity or signifier of social status. This is not to say that any of these practices should be suppressed, only that the risk of cultural imperialism should not be ignored as we strive for an informed citizenry.

No single answer to these concerns can be realistically posited, as case-by-case details must vary immensely; but with translations representing much less than three percent of publications, as Esther Allen noted in her remarks, the need for increased awareness is vital.

As conversations regarding this topic proceed, what strikes me as central reflecting upon the roundtable’s working, was the dialogic format the discussion assumed while attempting to negotiate these difficult and critical questions.

No easy solutions are readily available to help mediate the evolution of a new global culture; having said that, it is certainly my conviction that our endeavors should be informed by spaces of discussion that constructively engage and synthesize as diverse a set of points of perspective as possible.