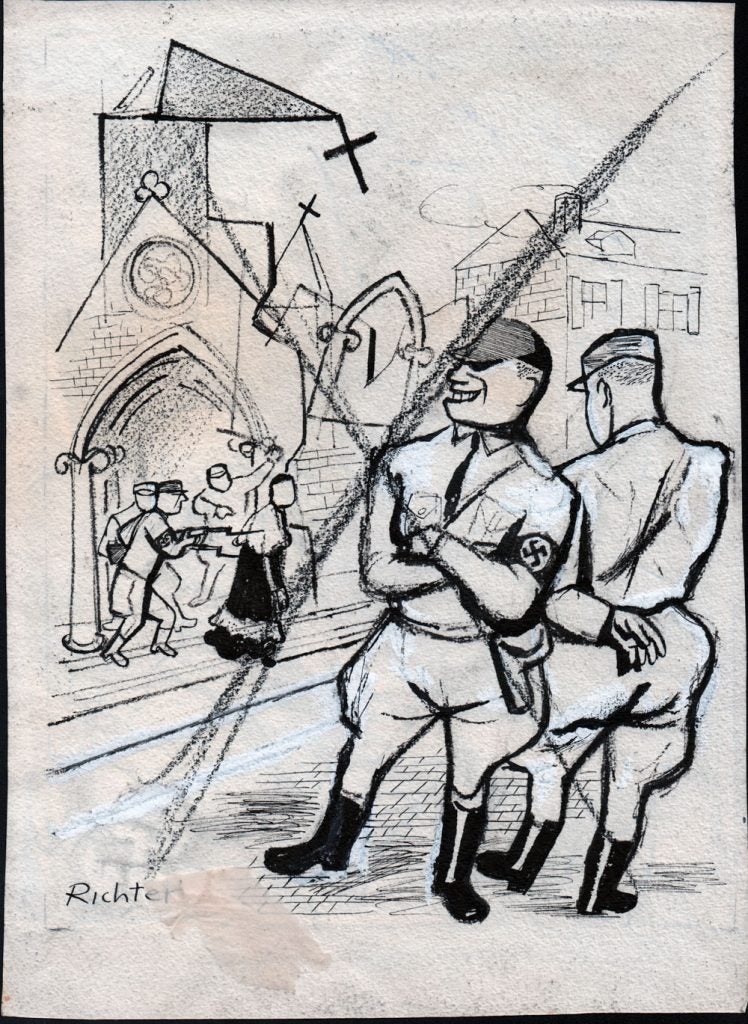

“Father Coughlin is already explaining it to the American people” (June 13, 1939)

by Mischa Richter (1910-2001)

13 x 9 in., ink and wash on watercolor paper

Coppola Collection

Eighty years ago, the growing cadre of fascists were providing support for an influential American to promote their agenda, favoring isolationism, anti-Semitism, and nationalism within the US, and keeping the US clear of participating in their rising ambitions in Europe. How much of this sounds familiar?

Mischa Richter (1910-2001) was a well-known New Yorker, King Features, and PM newspaper cartoonist who worked for the Communist Party’s literary journal “New Masses” in the late 1930 and early 1940s, becoming its art editor in the 1940s.

In this piece, from the June 13, 1939 issue of the New Masses, you see a priest being taken away from a toppled church by German soldiers. Hermann Goering and Hitler are in the foreground, with one of them saying, “Father Coughlin is already explaining it to the American people.”

Who is Father Coughlin? And how did he come to be understood as a mouthpiece for the Reich?

The answer is one of those interesting stories that we hear too little about. Father Coughlin was Charles Coughlin, the priest at the National Shrine of the Little Flowerchurch, close to Detroit, who espoused his anti-Semitic views from the both the pulpit and on radio.

First: a bit of background. In 1926, he was assigned to the newly founded Shrine of the Little Flower, a congregation of some 25 Catholic families among the largely Protestant suburban community of Royal Oak, Michigan. His powerful preaching soon expanded the parish congregation.

The same year, Coughlin began broadcasting on radio station WJR, in response to cross burnings by the Ku Klux Klan on the grounds of his church. The KKK was near the peak of its membership and power in Detroit. This second manifestation of the KKK, which was strong throughout the Midwest, was vehemently anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant. In response, Coughlin’s weekly hour-long radio program denounced the KKK, appealing to his Irish Catholic audience.

Radio station WJR was acquired by Goodwill Stations in 1929, and its owner, George A. Richards, encouraged Coughlin to focus on politics instead of religious topics. His broadcasts attacked the banking system and Jews, and his program was picked up by CBS in 1930 for national broadcast.

In January 1930, Coughlin began a series of attacks against socialism and Soviet Communism, which was strongly opposed by the Catholic Church. He criticized capitalists in America whose greed had made communist ideology attractive. And having gained a reputation as an outspoken anti-communist, Coughlin was given star billing as a witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee (July 1930).

Coughlin was a harsh critic of FDR, accusing him of being too friendly to bankers. In 1934, he used his visibility to establish a political organization called the National Union for Social Justice. Its platform called for monetary reforms, nationalization of major industries and railroads, and protection of labor rights. The membership ran into the millions.

After hinting at attacks on Jewish bankers, Coughlin began to use his radio program to broadcast anti-Semitic commentary. In the late 1930s, he supported some of the fascist policies of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Emperor Hirohito of Japan. The broadcasts have been described as “a variation of the Fascist agenda applied to American culture.” His chief topics were political and economic rather than religious, using the slogan “Social Justice.” During this time, he came to the attention of the Nazis.

In March 1938, Hilter annexed Austria. And in September 1938, British PM Neville Chamberlain returned from Germany, having signed the Munich Agreement and declaring “peace for our time” the night beforeGerman forces moved in and occupied a significant chunk of Czechoslovakia on October 1, 1938.

One of Coughlin’s campaign slogans was: “Less care for internationalism and more concern for national prosperity,” which appealed to the 1930s isolationists in the United States who turned a blind eye to the rise of fascism in Europe.

On December 18, 1938 thousands of Coughlin’s followers picketed the studios of station WMCA in New York City to protest the station’s refusal to carry the priest’s broadcasts. A number of protesters yelled anti-Semitic statements, such as “Send Jews back where they came from in leaky boats!” and “Wait until Hitler comes over here!” The protests continued for several months.

Coughlin was the modern forerunner of conservative talk radio, and he had a real following that was being influenced by outside forces. Historian Donald Warren, using information from the FBI and German government archives, has documented that Coughlin received indirect funding from Nazi Germany during this period, less than a year before the official outbreak of WWII.

This cartoon, from June 13, 1939, just three months before the Nazi invasion of Poland, gives a clear sense of awareness about the goings-on in Europe and the awareness of influence and propaganda getting to the US population through Coughlin.

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, the Roosevelt administration forced the cancellation of his radio program and forbade distribution by mail of his newspaper, Social Justice.

For the first time, thanks to new regulations created to deal with Coughlin, authorities required regular radio broadcasters to seek operating permits. When Coughlin’s permit was denied, he was temporarily silenced. Coughlin worked around the restriction by purchasing airtime in individual stations as a commercial enterprise, which limited his exposure and drained his resources.

In October 1939, one month after the invasion of Poland, the Code Committee of the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) adopted new rules that placed rigid limitations on the sale of radio time to ‘spokesmen of controversial public issues’. Manuscripts were required to be submitted in advance. Radio stations were threatened with the loss of their licenses if they failed to comply.

This ruling was clearly aimed at Coughlin, owing to his opposition to prospective American involvement in World War II. In the September 23, 1940, issue of Social Justice, Coughlin announced that he had been forced from the air “by those who control circumstances beyond my reach.”

There is also a near-finished, signed alternate version of the drawing on the reverse, which does not feature the identifiable Nazi leadership.