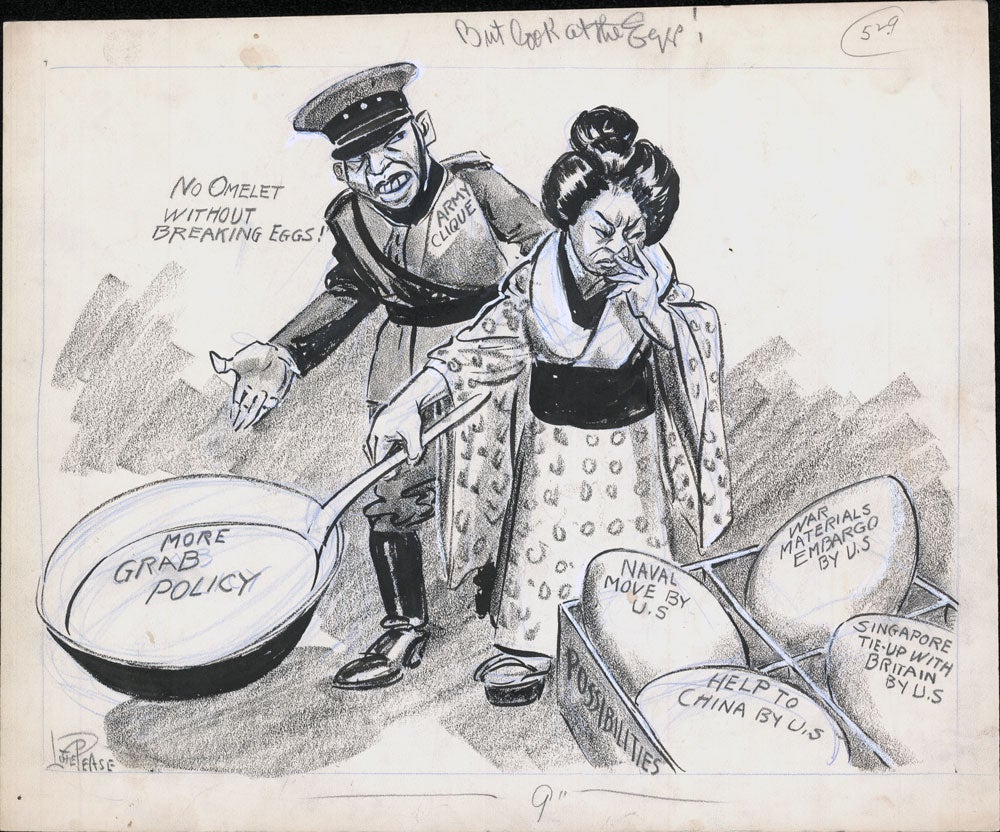

“But Look at the Eggs!” (August 10, 1940)

by Lucius Curtis “Lute” Pease, Jr. (1869 -1963)

14 x 17 in, ink, pencil and chalk on board

Coppola Collection

Pease was cartoonist for the Newark Evening News from 1914 to 1954, and received the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. He was a miner in Alaska for 5 years before beginning a career in art. He was an illustrator for the Oregonian and famously interviewed Mark Twain. From his retirement in 1954 until his death in 1963, he devoted himself to fostering his skills as a painter of portraits and landscapes.

The Imperial Japanese Army had gained a reputation both for its fanaticism and for its brutality against prisoners of war and civilians alike – with the Nanking Massacre being the most well known example. Even through the start of WW2 in Europe, Emperor Hirohito was focused on the ongoing wars in Asia, and particularly in China.

Pressure for a military response to threats from the West began to accumulate in the early 1940s, well before the attack on Pearl Harbor. A few of these that were percolating in late 1940 are the “eggs” that Japan was resisting breaking, opening up entirely new offensives in the Pacific region.

Singapore was of strategic importance to the British Empire second only to the Suez Canal. If Britain wanted to protect Australia and New Zealand, then Britain had to be a Pacific naval power. And Singapore was Britain’s gateway to the Pacific. Winston Churchill, newly installed as Prime Minister in May 1940, noted that since the German battleship Tirpitz was tying up a superior British fleet, a small British fleet at Singapore might have a similar disproportionate effect on the Japanese. The Foreign Office expressed the opinion that the presence of modern battleships at Singapore might deter Japan from entering the war.

In August 1940, Churchill sent reassurances to the prime ministers of Australia and New Zealand that, if they were attacked, their defense would be a priority second only to that of the British Isles. A defense conference was held in Singapore in October 1940.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese occupied the Shanghai International Settlement. A couple of hours later, landings began at Kota Bharu in Malaya. An hour after that, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942, and was described by Winston Churchill as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.”

In late July 1940, a cabinet change in Japan signaled a more aggressive Japanese policy in South-east Asia. With that, the United States imposed an embargo on aviation gasoline and high-grade scrap iron to Japan. This embargo affected only a fraction of exports to Japan, and the US government went to some lengths to justify the embargo on the grounds of American domestic needs rather than any displeasure with Japan. Still, the embargo signaled the Japanese that the United States would oppose any moves against Southeast Asia.

US likelihood of providing aid to China increased after July 7, 1937, when Chinese and Japanese forces clashed on the Marco Polo Bridge near Beijing, throwing the two nations into a full-scale war. As the United States watched Japanese forces sweep down the coast and then into the capital of Nanjing, popular opinion swung firmly in favor of the Chinese. Tensions with Japan rose when the Japanese Army bombed the USS Panay (December 1937) as it evacuated American citizens from Nanjing, killing three. The US Government, however, continued to avoid conflict and accepted an apology and indemnity from the Japanese. An uneasy truce held between the two nations into 1940.

In 1940 and 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt formalized U.S. aid to China.

The Japanese Government made several decisions during these two years that exacerbated the tensions in Asia. Unable or unwilling to control the military, Japan’s political leaders sought greater security by establishing the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” in August 1940. In so doing they announced Japan’s intention to drive the Western imperialist nations from Asia. However, this Japanese-led project aimed to enhance Japan’s economic and material wealth so that it would not be dependent upon supplies from the West, and not to “liberate” the long-subject peoples of Asia.