I came to Lauren Levin’s poetry in an extremely 2018 sort of way. Rather than hearing about Levin from a friend, I learned about her first book, The Braid, via your enemy and mine, Twitter!

Regardless of how I was introduced to it, since I began reading Levin’s work I’ve been transfixed. Her poetry is so personal as to be extraordinary, discursive in a questing, see-if-you-can-keep up sort of way. Levin’s poems are effortlessly long and interrogate difficult, easily fumbled subjects — motherhood, justice, her own whiteness, art — with sensitivity and intelligence.

Here are the first three stanzas from The Braid’s “The Diamond Skull”:

My purse has a funny smell. I root around in it and find

a piece of rotting pastry Alejandra didn’t finish eating, also a dropper sticky

with her medicine. When she used to shit each time she ate

Eight or so times a day—Tony and I had a disagreement

Tony wanted to open her diaper and let her shit directly on the changing table

I wanted her to shit in her diaper

but he didn’t like the idea of all that shit cloistered with her skin, maybe burning her

No one with large sums of money to disburse

wants anyone to do anything worthwhile with it

This summer Levin — who identifies as genderqueer and goes by both she and they — has been a columnist for SFMoma’s Open Space, writing essays about how “forms become circuits holding shame and belonging, running with and against our social and political modes.” In September, Levin’s second book will be published by the Oakland poetry press Timeless, Infinite Light (which MQR profiled in 2016).

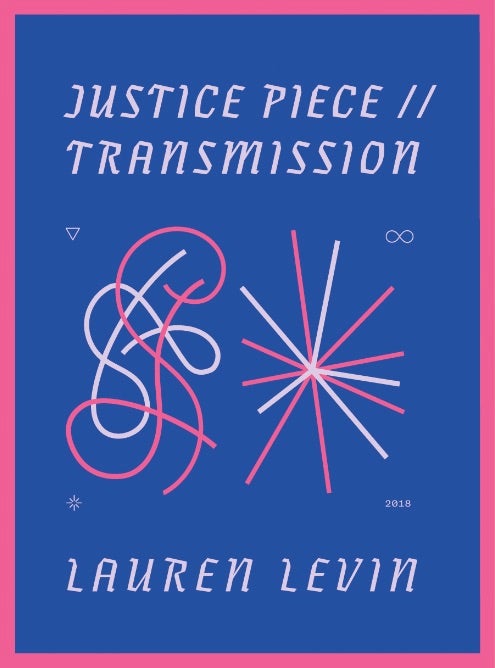

Justice Piece // Transmission, per its title, comprises two chapbook-length poems: “Justice Piece,” about justice and hypochondria via The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and “Transmission,” about family history (among other topics). It’s a remarkable book; reading it is like watching someone walk a tightrope.

I was thrilled to interview Levin over Gchat; because of the slight delay in communication, some questions and answers overlapped. This made for a slightly disjointed (if organic) conversation, but I’ve tried to preserve that feel. To paraphrase Matmos’s Drew Daniel, whose Twitter account first introduced me to Levin, her work is “wild and great.”

Where are you now?

Where are you now?

I’m at Highwire, a coffee shop in Berkeley. I often work here if I’m not in an office because I tend to immediately nap at home.

Do you have a day job?

I do have a day job, or day jobs. Right now I do grant writing for Timeless, Infinite Light, a queer art, poetry, and performance collective; I manage communications for a school; and I’m a columnist in residence for SFMoma’s Open Space. I also do some social media work. And I parent.

Lord. How do you fit writing in? Any special practices worth mentioning?

I do each of those things part-time, is the short answer. And Fridays are my day for my own writing, which I try to hold sacrosanct.

That’s disciplined.

I really hold that time. But the SFMoma essays are eating a huge amount of time, so my usual routine is off-balance.

Does it work? Only writing one day a week? Or do you find yourself working on things amidst other projects?

It’s hard. It works better if I read work that’s relevant to what I’m working on at night … otherwise it’s hard to just come into the world I’m trying to build completely cold after a week of other things. I wouldn’t call my writing a strict documentary practice but I do read and research a lot so that helps me steep myself in the atmosphere I’m working on creating.

What are you working on now?

I am working on a manuscript tentatively titled Reversi, which is a book-length project that deals with Othello and the tangles it creates around gender, race, and sexuality. And more loosely about how art interacts with politics, or how art and politics both shape form and a set of formal possibilities we use to live and act in the world.

That book is written in the form of letters to my friend Em Bohlka, who died in the Ghost Ship fire. So it’s intense!

Do you see your work as being intrinsically personal? Is the poetic personal, to butcher the slogan?

Though originally it was in a way, but it didn’t come to life or activate for me until I started writing it to Em, which happened after she died. Originally it was less personal, that is.

With Reversi, the new book, I was trying to think of it as trying to write without identification. In the sense that neither Othello nor Desdemona is a figure that’s possible to identify with in a straightforward way. Which doesn’t mean that it’s not personal, but that I was trying to tackle the personal in a different way.

Interesting. Yet it’s also directed at someone you lost. How do you place yourself in relation to others without identification being the primary circuit of relationship?

Yes, definitely. Em was a trans woman and so the book also relates to me working out my thoughts about gender and sexuality.

Othello wants to set up a polemical relationship around difference in which there’s a situation of mutually assured destruction between white women and black men. Em/s trans womanhood and my own relationship to my own gender have been useful in destabilizing that, if that makes sense.

But it is very personal. It’s become a grieving book, and a book about the Bay Area. And a book about my gender, and my friend and who she was, and a million different things.

Would you say place has a larger role in the new work than in your previous? Justice Piece // Transmission wasn’t overly concerned with place.

I think of myself as someone who follows threads, as an investigative, question-based writer. I write to figure out the parameters of my questions. So in that sense I think that I write around a constellation of issues that many people in the Bay are interested in. I’m a “Bay Area poet.” But I don’t know that I’m a place-based writer in the strict sense. I’m not very visual, to be honest, so my work is something of a mental landscape maybe? Though I love visual art!

I agree that you’re an “investigative, question-based writer.” Your work seems grapple with topics, or search for them, as they progress. Is that an organic thing, just how you write? Or are you striving for that effect?

I think it’s an organic thing, tied to the way that I think. I’m a very verbal, conceptual thinker with a very sensual side; my embodiment is really important to me. I think and I touch. But I always used to be confused by long descriptive passages in novels because I couldn’t visually process them.

So the writing/length is a way of embodying ideas and processing them?

I like that idea! I’m not sure, but it feels like a fit. That I embody ideas. Does that feel right to you?

It does. Would you say you’re interested in a kind of maximalism as a writer? In covering a lot of ground?

I’m thinking. It’s an interesting question.

I ask because both Justice Piece // Transmission start with your daughter and then move on to so much more in one page — hypochondria, your father and parking, etc.

I’m definitely beholden to writers for whom that is the case. Bernadette Mayer, for whom maximalism is a political ethos of sorts … a kind of feminist messiness or excess that works in opposition to leanness as a model of perfection. I also see it as “turtles all the way down.”

Would you say that you’ve moved toward length as you’ve matured as poet? Or has this always been your thing, seemingly discursive work?

Like the part in Justice Piece where I mention how pleasurable it is to find something that works well for my book (I think that was about the Led Zeppelin symbols) but then thinking, everything is inflected by patriarchy. So to find it everywhere really requires no art. And I’m attached to Jewish traditions of answering a question with a question. Which is a kind of maximalism.

So it’s part-intellectual interest, part-upbringing.

I think it’s been part of my maturation as a poet/writer.

It’s also just how my brain works. I’m a very associative thinker. I think part of maturing as an artist is figuring out that the things that may have felt like a lack or an inadequacy can be strengths if you just double or triple down on them. Go all the way into the peculiarity and particularity of one’s own thinking.

You’re not planning to go the other direction, to begin writing hyper short haiku-esque things?

I don’t know that I’m planning to write haiku. But I am feeling a bit of a longing for poetry poetry. But it will probably still be long and discursive.

I want to return to Led Zeppelin, because I was surprised to see them in Justice Piece, given Led Zeppelin’s reputation for misogyny. Aside from the ex-boyfriend connection, can you talk about their inclusion in the poem?

Well, Justice Piece starts with Jennifer Tamayo asking me those questions. What does it mean to you to be white? How does it show up in your work? What is justice? So those questions sent me into something of a genealogical mode. A genealogy of morals. What cultural objects relate to my identity?

Led Zeppelin represents a particular kind of whiteness, and white maleness in time.

Yes, and I formed my identity around those representations, as we all do, I guess. I think that the book Disidentifications by Jose Munoz is so important to all of this. Do you know that one?

I don’t.

My brief summary is that it’s about queer people of color reading against the grain. If you don’t have representations of yourself in mainstream culture, there’s a way of identifying with pop culture that’s neither exactly with you nor exactly against you that allows you to make space for yourself.

And when you were younger you might have identified with Led Zeppelin.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show probably represents that in Justice Piece the most.

Yes, I was going to get to The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

But yes, that question of how do you identify with Led Zeppelin, the ultimate rock god male subject, if you are coded as an object? It’s inherently complicated but not impossible, you know? I think there’s something in there where I quote the book I’m With the Band on Jimmy Page’s beautiful long hair and how he’s primping.

Yes, and how nice it smelled. From Justice Piece: “He used Pantene products, and whenever I smelled them, for years // afterward, // I remembered being buried in his hair.”

There are these moments of hyper-femininity embedded within hyper-masculinity and part of the work is unearthing these moments.

Re: The Rocky Horror Picture Show: While it’s about challenging normative gender roles, etc., the sexuality in Rocky Horror is divorced from the biological outcomes of sex (i.e., children). Sexuality as a mode of self-expression vs. procreation. How do you see Rocky Horror being connected to childbirth, and more generally, to shame, as you write “being shamed in your body / shamed body events / childbirth, aging, / beauty, justice”?

That’s a complicated one. Lemme think for a sec. Well, Frank-N-Furter does make a child, right?

Yes, I guess that’s right!

If [the monster in] Frankenstein is an embodiment, in part, of Mary Shelley’s fear of childbirth and attempt to articulate what it means for the woman artist, you could look at The Rocky Horror Picture Show in that Frankenstein lineage. Or you could say that’s a bit of a stretch!

He creates Rocky, but there’s no baby.

It’s true. I found the existence of this sequel really weird for that reason. From Wikia, “Rocky Horror: The Second Coming is a failed project, a never-made stage sequel to The Rocky Horror Show by Richard O’Brien … The play would be set nine months after the events of The Rocky Horror Show and would feature a pregnant Janet carrying either Frank’s or Rocky’s child.”

That would have been interesting (for our conversation at least). Frank creates Rocky but it’s divorced from sex. In the movie, sex is a way for characters to express and find themselves.

Hmmmmm. This isn’t something I’ve really clearly articulated for myself. There’s definitely a strain in Justice Piece about reproductive labor and how it’s assigned. There’s a classical definition of justice as being the way in which each person or group is “served” the proper portion, the portion they deserve. Of course historically, racism and misogyny and resentment have done a lot of that “assigning.” So I suppose I’m interested in works of art and popular art/culture that detach what you receive or how you are allowed to be from what you “deserve.”

What about shame — The Rocky Horror Picture Show on shame/not being shamed — and how you see shame in your work?

The Rocky Horror Picture Show does that in a sense by disarticulating gender.

It does. That’s Frank-N-Furter’s role in the story, right? Though of course he’s also a menacing space alien.

And seeing sex and gender play as vehicles for liberation. Frank-N-Furter makes a child but has sex with it rather than taking care of it!

So he’s both liberating and threatening. But not exactly dad of the year.

I never saw Frank-N-Furter as threatening, which maybe is why I’m interested in it. For me, it was purely libidinous. Like David Bowie/Jareth in Labyrinth!

But as I write in the book, my take on The Rocky Horror Picture Show did not translate to my partner — he saw the movie as an unintelligible mess — and that interests me, too. These personal reads and mythologies on artworks, our own disidentifications. Can I loop back to another element of your question?

Please do.

When I said that I was trying to think about justice and how it’s an idea that each one gets their just desserts and in the shitty normative form of that, it often means women “get” the housework or the emotional labor, black people “get” police brutality and environmental racism, etc. — the short end of the stick in all regards, in our white supremacist culture. There are different ways to try to disrupt that process or think about justice differently. The Rocky Horror Picture Show is one way.

And do you think of your work as a way to disrupt that too?

I would like to.

Do you think of your writing as a form of activism?

I was just thinking that The Rocky Horror Picture Show is trying to disrupt gender (albeit in a commercial way). So messing with what a man or a woman is. Why should being a man or a woman or both or neither be connected to doing housework? Or getting attacked by police? I’m trying to think about both “ends” of that justice equation, as it were.

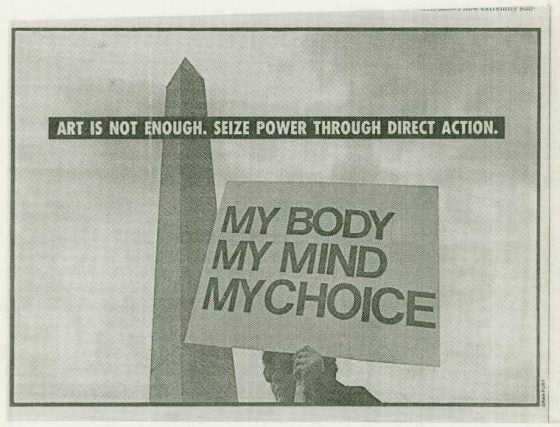

I think my writing is connected to my politics and ethics and to my desires. I see it as a way of trying to articulate forms to make my desire and my life possible. And I would love for it do that for others, if others find that in it. But I don’t see it as sufficient. I mean, it’s not getting children out of cages. But I think all art is political, I suppose.

So you don’t see art as a replacement for other forms of activism or resistance?

I don’t see it as a replacement but I also don’t see it as inadequate — it just has a certain repertoire. I have no problem with anyone saying my work is activist or political.

That makes sense.

I mean, it is. I just don’t want to make grandiose claims about what art can do. I love it beyond measure but that’s because I’m an artist/writer. But I have needed it. Do need it. And I get life from the work of my friends.

I want to get to my last big question. While reading Transmission in particular I thought about how “true” your work is; it’s a strikingly honest poem, and seems not to dissemble at all.

So: do you see your speaker as a “speaker”? Or do you see the work as you, working things out on paper? And are you intentionally fudging details? And why are some things out of bounds (shitting after giving birth) when little else seems to be?

Well, first let me offer a P.S. to the last question: Gran Fury’s “Art is Not Enough.”

I have an interest in verisimilitude and in artifice, in the sense that any written work or artwork is constructed, however artless it appears — or feels to the person who makes it, for that matter. There are ways of disrupting the entrance of personality into the work, like chance operations or documentary practice. But then in a sense you’re just stepping back from the entrance of personality one remove.

So your speaker isn’t a half-fictionalized Lauren Levin, a la Knausgaard?

As in, the artist’s personality enters in the choice of operations, or the stitching together of collage material. On the other side, “confessional” material is also constructed by the artist, which doesn’t mean that it’s not also “honest.” But am I honest with myself?

How do you feel about that label? Confessional? It’s gone out of vogue.

I think it’s a “both/and” kind of answer. The narrating voice is me and also not. And I kind of love the label confessional because it is out of vogue.

I’ve never had an issue with it.

Think of me as a kind of forensic scientist of myself and everything else.

Plus so much writing these days is really stripped of artifice.

One of the things I said about writing Transmission was that it’s asking, “If I am the symptom, what is the cause?” So in that sense nothing I’m putting across is natural, even though it’s all (or most of it is) true.

I’m trying to think about what occasioned and occasions me. The constraints (political, historical, personal) that give rise to my personality. “Now I am quietly waiting for the catastrophe of my personality to seem beautiful again, and interesting, and modern.” (Note: Levin is quoting Frank O’Hara’s “Mayakovsky.”)

Was Transmission a hard poem to write? Or publish?

Um, yes. Both. It was so hard/painful to write. And I think I’m kind of pretending that I’m not publishing it. LOL/sigh.