Glass Poetry Press is a micro-press in Toledo, Ohio publishing four to six hand-bound poetry chapbooks per year. To date, the press has produced twelve chapbooks, including titles such as What Is Not Beautiful, by Adeeba Shahid Talukder, To My Body, by Steven Sanchez, Bad Anatomy, by Hannah Cohen, and more. In addition to the press, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, publishes poems online in monthly issues. In this latest installment of our Small Press Series for MQR Online, poet and founding editor Anthony Frame shares why he started Glass Poetry, what he looks for in a poetry submission, and recommends upcoming titles from outstanding Glass writers. This interview was conducted over email.

Could you tell us a bit about the founding of Glass Poetry? What inspired you to start it, and what was your original mission? What could Glass add to the literary journal conversation that had never been heard before?

Glass: A Journal of Poetry started in 2008 as an online poetry journal that released three issues a year. Over the years, it evolved quite a bit, but its general idea was to make great poetry available for free online. My wife, Holly Burnside, and I started it and we coedited it for six years. When we were thinking about starting a journal, a few of our own poems had been published in new, online journals that then closed and disappeared from the web within a month or so of our work appearing on their site. In a lot of ways, it was out of frustration that we decided we wanted to start a journal that wouldn’t disappear within a year.

It’s kind of hard to remember what early 2008 was like — George W. Bush was still President, the war in Iraq was on everyone’s minds, and the Great Recession hadn’t yet happened. Online journals were still a fairly new thing. When we started Glass, we often had poets respond to our acceptances asking if there was a print version because they weren’t interested in their work being limited to pixels. Obviously, now the online literary scene is a vibrant and exciting part of the literary community and I’m proud to be a part of that. But our goals were, and my goals remain, simple: make great poetry available for free on the Internet. The journal’s explicit mission has evolved to also seek to be a space where historically underrepresented writers will be treated with as much respect as poets who look and live like canonized poets. Even in 2008, that was a part of our mission, though we didn’t necessarily say it then explicitly.

In 2014, Glass: A Journal of Poetry ceased publication. In 2016, Glass Poetry Press began printing chapbooks, and one year later, the journal reopened. What informed these administrative decisions?

Holly and I kept the journal going for six years but, in 2014, as we were working on what would become our last issue, we had to think seriously about whether we were going to be able to continue to publish the journal. Our submission response times were getting really long and our other responsibilities in life were growing. We were each making career changes and we simply felt, at that time, that we weren’t able to give the people who were submitting and who we were publishing the amount of attention and care that we would want from a journal. We made the difficult decision to cease publication, but we also made a commitment to our poets that we would keep their work available online for as long as we could.

After we closed the journal, I still wanted to be an editor. I still wanted to work with other writers and provide a space for the work that I loved. In 2016, I won an individual excellence award from the Ohio Arts Council and decided that I wanted to use a portion of that grant to give back to the poetry community. So, I developed the Glass Chapbook Series. I started soliciting the first five chapbooks shortly after I learned I had won the award and pretty quickly scheduled Ariel Francisco’s Before Snowfall, After Rain, which came out in August 2016. I loved the idea of working on chapbooks because I love the short form poetry collection and I wanted the chance to work closely with an author on a collection of poems, rather than just one or two of their poems, like we did in the journal.

I also got a little antsy because it took quite a while to gather those first five manuscripts and to figure out how to turn them into chapbooks that I and the authors would be proud of. Since I had the Glass website, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry still had a bit of a reputation, I decided I might as well reopen the journal. I also thought the journal would be a nice partner to the chapbook series — that they could comment on and drive interest in each other.

In June 2016, Glass returned as an online journal that published a single poem (occasionally two) each week. As with everything, I’ve tried to let the journal evolve and, because I was receiving so many submissions that I absolutely loved, in 2017 I retooled Glass into a monthly journal, which lets me publish ten to fifteen poems each month instead of just four. I loved the weekly focus on just a single poem, but I also love the way the poems in each issue create a conversation among themselves. In the end, I’m very happy with the decision and with the overall evolution of the Glass project.

Editorially speaking, what makes a book a Glass chapbook? What are its necessary ingredients?

I’m hesitant to say too much in regards to what makes a chapbook a Glass chapbook because every time I do, someone sends in a manuscript that is completely the opposite and is absolutely brilliant. Certainly, if someone had asked me this when I started Glass, I would never had said that I was looking for a weird collection of cooking recipes hiding as love poems from a young Nigerian poet, but during my first open reading period, Logan February sent me exactly that, and How to Cook a Ghost is possibly the chapbook I’m most proud of publishing (because I’m not sure how many other publishers would have taken a shot on it).

I tend to be drawn to chapbooks where the poems feel like they are meant to be together — as opposed to just a collection of the poet’s best pieces. I think coherence is really important for chapbooks because they are, in a lot of ways, meant to be read in a single, immersive sitting. I’d also say that I’m drawn to manuscripts that feel finished. There are chapbooks that feel like they are one section of a full length and there are chapbooks that feel like they are intended to be their own thing. I find myself drawn to the latter. I think Jennifer Givhan’s Lifeline is a really interesting example. I remember when she offered that manuscript, I thought how clearly these poems were speaking to each other in an obvious and consistent way. She’s since had three full lengths released and I’ve been fascinated to see the poems from Lifeline appear scattered within these three full lengths in completely new contexts.

The main thing is that I am always looking to be surprised. I’m always looking for the manuscript I never expected. And I’m looking for the manuscript that knocks my socks off while I’m reading it, after I’ve read it, and while I’m rereading it. Long story short: I’m looking for what I haven’t seen before. I’m looking for what I don’t know I’m looking for.

As a small and independent press, what can you do that bigger publishers can’t?

I think the smallness of Glass gives it a lot more flexibility. I don’t want to assume what bigger publishers can and cannot do, but my experience with Glass is that I am able to take each project and adjust my role based on its needs. I’m able to develop a project like Pulsamos, our special issue of poems by LGBTQ poets in response to the massacre at Pulse Nightclub, and put it together quickly (Pulsamos was released around six or eight weeks after the shooting). Similarly, I’m able to curate a similar special issue focusing on the upcoming midterm elections, which will be released on the morning of the elections, and with that, I can move much more slowly, soliciting work and allowing the poets to take their time to consider how they want to respond to our current political/cultural moment.

With the chapbooks, I can adjust how the press approaches each manuscript. I can adjust how we approach the cover design and development, allowing the author a lot of input into choosing the cover art. I’m able to approach the interior layout of each chapbook differently. Basically, I can reinvent the press for each chapbook, if needed. For example, when Jenn Givhan sent me Lifeline, I looked at her poem “Girl with Death Mask,” a brilliant poem with long lines and separate block texts inserted into the lines. I could have decided that my limitations as a small press were unable to do some of the amazing centerfold poems we sometimes see in Poetry Magazine. I could have told Jenn that “Girl” was simply not possible and we’d have to cut it. Instead, I started playing around with the layout template and found that I was able to spread the poem across two facing pages, almost like a double splash page sometimes seen in graphic novels. I sent it to Jenn to see if she was okay with the decision and she loved it. And then, we were able to look at the exact places where I was placing the page fold so that we could use that forced margin as a new internal line break, allowing Jenn to add additional emphasis on certain images because of the design choices we were making.

I found myself in a similar situation when Jennifer Met sent Gallery Withheld, a collection of concrete/shape poems. Most of the poems wouldn’t fit the page size I’m forced to work with so, in addition to spreading some poems across multiple pages like we did with “Girl with Death Mask,” we also started looking at ways to rotate the poems on the page. The final result was a manuscript that the reader has to physically turn in order to read the poems, and that flipping of the book became part of the experience of reading the poems. Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib described it as “the page itself is made into a new machine, a vehicle for a grander experiment.” I think this flexibility is probably the greatest benefit of being a micro-press and it’s one of the reasons I try to limit my projects so I’m able to give each project enough attention and fully exercise that flexibility.

Are you ever concerned about staying competitive with the Big Five publishers?

Not at all! Honestly, I probably can’t name many of the Big Five. Those kinds of publishers are simply working in a very different space than I am and they’re doing very different things than I am. Because of that, I don’t think of myself as being in competition with them. In my mind, that would be like the Detroit Tigers thinking of themselves as competitive with the Cleveland Cavaliers. None of this is a condemnation of what the Big Five are doing and it’s not a statement of my superiority either. We’re just playing in very different fields with very different equipment and, where our readership overlaps, I don’t think it’s a matter of someone saying, “I can either buy Adrian Matejka’s new book from Penguin or I can buy the new Glass chapbook.” I tend to think that readers will buy both when they’re able to buy each. And, for what it’s worth, Matejka’s new book is phenomenal!

How does competition play into the micro-press scene?

Publishers like Hyacinth Girl Press, Damaged Goods Press, and Seven Kitchens Press run in very similar ways as mine, publish similar or the same authors as I do, and have the same audience as Glass. They are on the same field and are using the same equipment, yet I don’t feel like I’m in competition with them either. I one hundred percent feel like the work Glass does is in conversation with these other small and micro-presses. I’ve learned so much from them (in fact, my entire publishing model is directly inspired by Hyacinth, and Margaret Bashaar has been a constant champion of Glass) and I hope that I am able to help them in any way needed. With small presses, I definitely feel like we’re all in this together and my experience has been that we are a community rather than a group of competitors.

In terms of Glass: A Journal of Poetry, what are you looking for in poetry submissions? What kind of poems excite you?

I’m really looking for beautiful poems. They can be lyric, narrative, or experimental, but I’m always drawn in by a series of beautiful images. This is probably the first thing that helps a poem rise above the rest of the submissions. I’m also looking for a poem that feels cohesive, that feels in some way consistent from start to finish, and that feels like these words/images/lines are meant to be next to each other.

I’m finding myself drawn to poems that have a sense of awe. This can be positive and negative — I think there’s a decent balance in the Glass poems that focus on joy and those that focus on sorrow (and probably the majority rely on both) — but I think that awe is definitely there. Much like the chapbooks, a journal submission that makes it through the reading process for me is one that I keep coming back to over and over, one that sticks in my mind even after I’ve started reading another submission. I think it is that awe that causes a poem to attach itself to my brain.

Beyond that, I’m usually pretty aware of my independence — of the fact that I don’t have to answer to anyone except for myself, the readers of Glass, and the poets I’m publishing, which gives me a lot of freedom that some other editors don’t necessarily have. I think this draws me to those poems that I love but I’m not sure another editor or editorial team would say yes to easily. The thing I’ve been telling people who ask what they should send to Glass is that they should send their weirder poems, the ones that they love, but that don’t feel like a poem other journals are likely to be interested in. Nothing excites me more as an editor than reading through a packet of poems and suddenly being hit with a piece that looks/feels/sounds/moves unlike anything I’ve seen before.

What are your goals for Glass Poetry Press in the next five years?

I definitely plan to keep doing what I’ve been doing — a monthly online journal and five chapbooks each year. I have big ideas all the time about what I’d love to do with the Glass project. I would love to do a broadside series, but I would want to do it old-school Gutenberg-style with a hand press, and that would be a major investment of both money and time, and I don’t really have either. I’d love to start a reading series here in Toledo that brings in national poets. In my dream, we’d host the readings in the Great Hall at the Toledo Art Museum, which is where they display all of the giant, ten-foot-tall paintings. But again, that would require money and time I don’t have. I’ve also been playing around with the idea of a podcast. My idea is to have these very casual conversations with a poet where we read poems we love and then chat about them, which wouldn’t require much, if any, financial investment, but the time factor would still be an issue (and my general shyness would also be a bit of a barrier).

More than likely, in five years, Glass will look a lot like it does right now. I’d rather keep the scope of the press the same and maintain the quality than try to take on too much and risk lessening the quality of the work and the final product.

You are an artist as well, with one full-length book (A Generation of Insomniacs) and four chapbooks (To Gain the Day, Where Wind Meets Wing, Everything I Know…, and Paper Guillotines) to your name. How does running Glass influence your own career as a poet?

Every time I read a submission, I learn something. Every time I work through a manuscript with an author, I learn something. All but my most recent chapbook came out before Glass became a press and I can definitely say that my approach to putting together my most recent chapbook, Where Wind Meets Wing, and my pre- and post-production approach were heavily influenced by my work on Glass. Being able to see what happens behind the scenes, being able to see in real time how much social media affects pre-sales/sales, understanding how decisions are made and how some of those decisions are determined by what the press is technically able to do — all of these played a part in how I put that chapbook together, how I went about submitting it, and how I went about promoting it.

Whenever I read a submission, either for the journal or the chapbook series, I have to think very consciously about what is attracting it to me, what is making me less interested, etc. Ultimately, these are aesthetic preferences, but they’re also craft lessons for me. If I unpack a series of images in a submission and make judgments on why they are or are not working, then later on when I’m working on my own poems, I’m going to do the same thing with my work.

Can you recommend a few upcoming Glass titles we should keep on our radar?

We just had two titles come out that are phenomenal. In August, we released Anna Meister’s As If, which is one of my absolute favorite chapbooks ever. In it, Meister has created a single, chapbook-length exploration of mental health and PTSD, with gorgeous images and language. I’m also extra thrilled by this chapbook because I’ve long loved Meister’s work and solicited As If during a conversation with Anna on Twitter. I was shocked and thrilled when she replied, “Yes.”

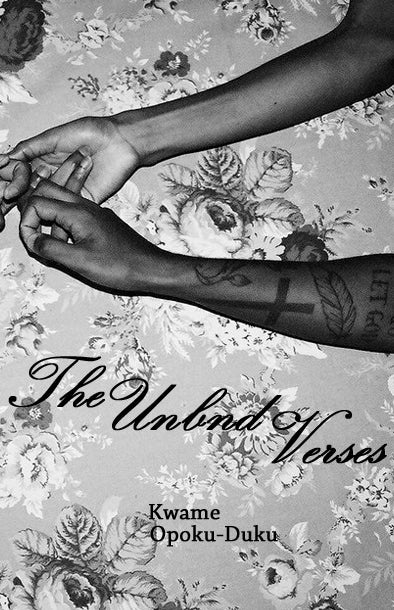

Just a couple of weeks ago, we released Kwame Opoku-Duku’s The Unbnd Verses. I remember when this manuscript came in as a submission and how absolutely blown away I was by it. The Unbnd Verses is one of those manuscripts that reminds you of the holiness of verse. Kwame has created, in brief, a new Biblical book — one that is fully modern, fully honest, fully raw, and fully drop dead gorgeous.

Then, over the next few months, we’ve got three more chapbooks coming. Praise for Lesser Gods of Love by Noor Ibn Najam (January 2019), Diary of a Ghost Girl by Shay Alexi (March 2019), and dolores in spanish is pain, dolores in lolita is a girl by Ashley Miranda (May 2019). I really can’t speak highly enough about each of these — I’m so excited to start sending them out into the world. Praise… deals with being both transgender and a part of the Arab Diaspora community. Noor’s poems are intensely beautiful and powerfully crafted. Diary… is a fantastic exploration of gender, identity, and culture, and it is unquestionably brilliant. Shay also has roots in spoken word poetry and I love the influence that has on this manuscript. Lastly, Ashley Miranda’s dolores chapbook approaches the topic of rape/sexual assault/abuse by deconstructing the character Dolores Haze from Lolita. Ashley is a fierce critic of rape culture and the effects it has on girls. She navigates us through her subject matter in poems that perfectly balance the rawness of survival and the strength needed to survive, all in stunning language. I seriously cannot wait for readers to get their hands on these chapbooks.

What books are in your personal TBR stack?

Kaveh Akbar has been saying for more than a year that we are living in a golden age of poetry and he’s so very right (and his chapbook, Portrait of the Alcoholic, and his full length, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, are definitely on my To Be Reread list). A few in my stack: Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About The Trees Without The Blood, Fatimah Asghar’s If They Come For Us, Joshua Jennifer Espinosa’s Outside Of The Body There Is Something Like Hope, Jennifer Givhan’s Girl with Death Mask, torrin a. greathouse’s boy/girl/ghost, Emma Bolden’s House is an Enigma, Julian Randall’s Refuse… I could go on and on. I’m also really looking forward to Lisa Fay Coutley’s Tether (forthcoming 2020), as well as Adeeba Shahid Talukder’s Shahr-e-jaanaan: The City of the Beloved (forthcoming 2019).

It’s clear the poetry gods are going to continue to bless us for a long time.