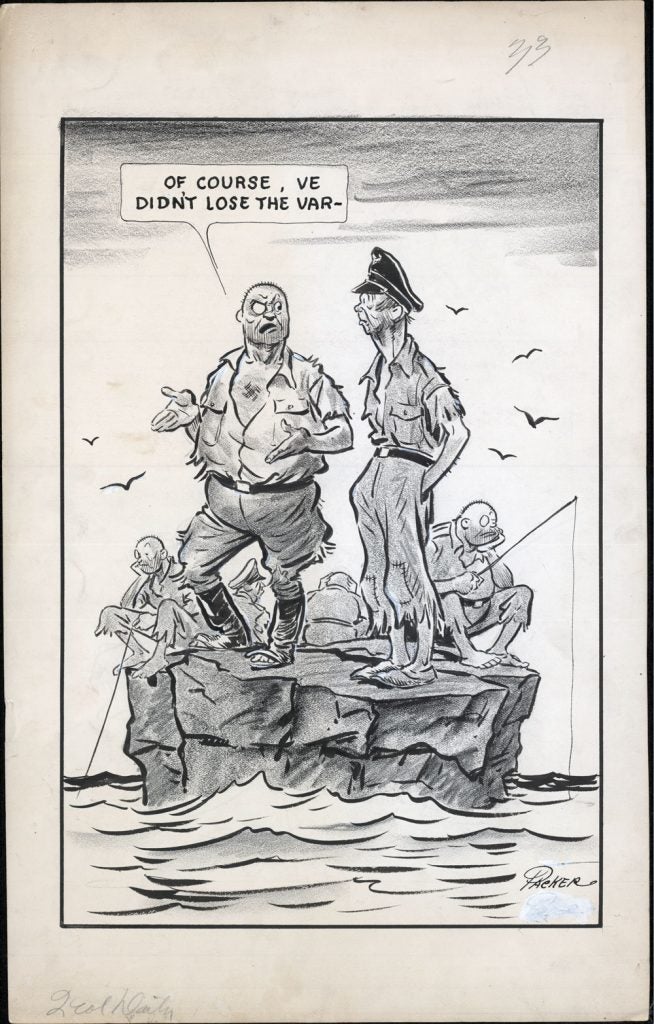

“Of course, Ve didn’t lose the var – ” (ca. 1945)

by Frederick Little Packer (1886-1956)

15 x 23 in., ink on heavy paper

Coppola Collection

Packer worked at the LA Examinerfrom 1919-1931, and then moved to the New York Daily Mirrorin 1932.

His cartoons and posters for the World War II defense effort earned him citations from the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize on May 5, l952 for his Truman Cartoon, “Your Editors ought to have more sense than to print what I say,” which appeared in the “New York Daily Mirror” of October 6, l951.

In August 1953, he was invited by the Library of Congress to make a gift of his original drawings to its permanent collection.

Between October 17 and February 5, 1945, the total of German POWs taken in northwest Europe increased to 860,000, including 610,541 German soldiers who surrendered on the Western front. By no means the caricature of inferiority that the propaganda painted, the capability of the German army was substantial.

Max Hastings, writing in “Their Wehrmacht Was Better Than Our Army” (The Washington Post, May 5, 1985), notes that tt was the superiority of Allied numbers that was ultimately decisive. The Second World War in Europe was a victory of quantity over quality.

The final German armed forces communique, issued on May 9, 1945, read: “In the end the German armed forces succumbed with honor to enormous superiority. Loyal to his oath, the German soldier’s performance in a supreme effort for his people can never be forgotten. To the last, the homeland supported him with all its strength in an effort entailing the heaviest sacrifices. The unique performance of the front and homeland will find its final recognition in a later, just judgment of history. The enemy, too, will not deny his respect for the achievements and sacrifices of German soldiers on land, at sea, and in the air.”

After the war, Winston Churchill commented on the conflict more truthfully then he had while it still raged. In his memoirs, he compared the record of British and German forces in the Norway campaign of April-June 1940 — the first time during World War II that soldiers of those two nations faced each other in combat. “The superiority of the Germans in design, management and energy were plain,” Churchill wrote. “At Narvik a mixed and improvised German force barely six thousand strong held at bay for six weeks some twenty thousand Allied troops, and, though driven out of the town, lived to see them depart. In this Norwegian encounter, some of our finest troops, the Scots and Irish Guards, were baffled by the vigour, enterprise and training of Hitler’s young men.”

“Unfortunately we are fighting the best soldiers in the world – what men!,” exclaimed Lt. Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 15th Army Group in Italy, in a March 1944 report to London.

artillery lieutenant Eugenio Conti, who was deployed along with units of other European nations in the savage fighting on the Eastern front in the Winter of 1942-43, later recalled: “I … asked myself … what would have become of us without the Germans. I was reluctantly forced to admit that alone, we Italians would have ended up in enemy hands … I … thanked heaven that they were with us there in the column … Without a shadow of a doubt, as soldiers they have no equal.”

Milovan Djilas was a senior figure in Tito’s anti-German partisan army, and after the war served in high-level posts in Yugoslavia. Looking back, he recalled the German soldiers’ endurance, steadfastness and skill as they slowly retreated from rugged mountainous areas under the most daunting conditions: “The German army left a trail of heroism … Hungry and half naked, they cleared mountain landslides, stormed the rocky peaks, carved out bypasses. Allied planes used them for leisurely target practice. Their fuel ran out … In the end they got through, leaving a memory of their martial manhood.”