Translations and Interpretations of the Chinese Folk Story “Journey to the West” (西遊記)

Link to my HathiTrust Collection: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/mb?a=listis;c=437436280

Background:

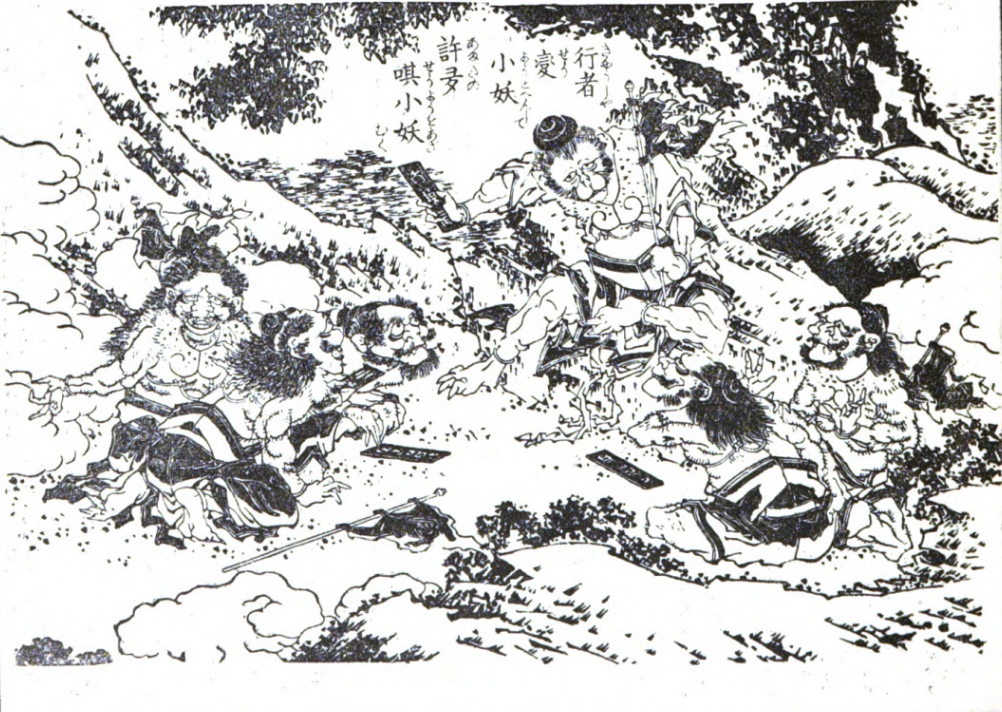

The “Journey to the West” is a 16th Century Chinese novel written by poet Wu Cheng’en which follows the journey of the Buddhist Monk Xuanzang who in the original retelling was tasked with bringing back sacred texts from the “West” (most likely Central Asia or India). Along his journey, he meets multiple anthropomorphic travelling companions. Among them the Monkey King “Sun Wukong” and the Pig Man “Zhu Bajie”. Each of the main characters in “Journey to the West” has their own extensive backstory and narrative history. Typically these separate stories like “Monkey King” are regarded as all falling under the collective umbrella of “Journey to the West”.

My Collection

The goal of my collection is to investigate the different retellings of the story through the dimensions of language and time. As a kid, we had an old VHS tape that we passed around with the neighbors that had a Chinese language cartoon of “Journey to the West”. Upon researching the original story, I was surprised how the version I remembered from my childhood differed significantly from the original retelling. This got me curious as to how the story evolved over time and the role language might have played in its evolution. As a result my collection contains versions of “Journey to the West” in Chinese, English, and Japanese with varying publication dates from the 16th century to the modern era.

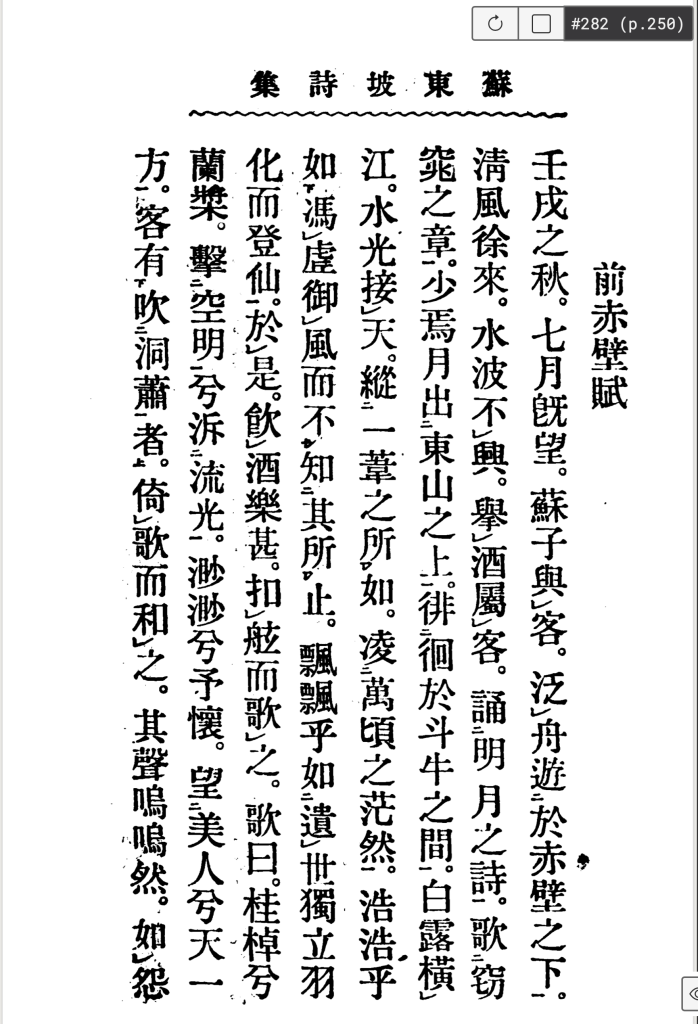

Below is a page from the first volume of a printing of the original “Journey to the West”. Note the right to left column reading convention as well as the traditional writing of the characters. What is particularly interesting is the use of modern Chinese punctuation which was only introduced in 1920 in conjunction with traditional Chinese judou markings. This is anachronistic considering the publication date given by HathiTrust of 1696 where traditional Chinese punctuation would still have been used. This raises the question of how HathiTrust determines the publication date when collecting metadata for sources. In the Sawyer Seminar, it was mentioned by librarian Leigh Billings that OCR provides the basis for a lot of the meta data generated by HathiTrust. In this case there was no indication in the Full View of the source that a publication date was provided so it raises the question as to both what extraneous sources HathiTrust relies on for metadata as well as the credibility of such sources. Much like the upside down Persian work in the Lightning Talk, this source is also mis-catalogued in HathiTrust.

I was inspired to look deeper into the evolution of Chinese writing scripts by my classmate Yao Tan’s blog post about the lingual speciation of Japanese Kanji and Chinese. Connections like these don’t seem to be picked up by OCR very frequently so it seems to be a way for humans with domain specific knowledge to find valuable connections ignored by machine learning.

Analysis:

Translations and Interpretations of the Chinese Folk Story “Journey to the West” (西遊記) Read More »

You must be logged in to post a comment.