“And what, sir, are your intentions…?” (1940)

“And what, sir, are your intentions…?” (1940)

by William “Bill” Crawford (1913-1982)

19 x 22 in., ink and crayon on Glarco Illustration Board

Coppola Collection

Although we rely on our historians to tell us these stories, my interest in these political cartoons continues to be inspired by just how informed at least some people were about the comings and goings related to the beginnings of WWII. Here we have a character (Sumner Welles) interviewing a weaponed-up Hilter. The date is March 1940, and we see a series of military victories summed up from the last five years. The question “what are your intentions?” is clearly naïve, and Sumner a fool, correspondingly, for note seeing what is front of his face. In case there is any question, the answer is there: peace is not in the cards, there are only pigeons (the marks in a scam) to be had by whatever might be said by the gentleman from Berlin.

Why does this sound so vaguely familiar in 2016?

The story of March 1940 is important to the War. Coming off the first land grabs by the Nazis in 1939, the next wave of invasions was just months away. Italy was hanging back, still, and the US was sending a diplomat to Europe for meetings with all the principals.

Benjamin Sumner Welles (1892 –1961) was a major foreign policy adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and served as Undersecretary of State from 1936 to 1943, during FDR’s presidency.

The secret protocol contained in the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union had relegated Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to the Soviet sphere of influence. Mussolini remained “non-belligerent” (the Duce hated the term “neutral”), which annoyed Hitler, and particularly because Italy did not join the September 1939 invasion of Poland.

On February 9, 1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the following statement at his regular press conference: “At the request of the President, the Under Secretary of State Mr. Sumner Welles, will proceed shortly to Europe to visit Italy, France, Germany and Great Britain. This visit is solely for the purpose of advising the President and the Secretary of State as to conditions in Europe.”

On 1 March 1940, Sumner Welles arrived in Berlin. He had just visited Mussolini in (neutral) Italy and would be going on to London and Paris afterwards. His instructions from President Roosevelt, as far as we know, were to seek a basis for peace and to offer the United States’ services as mediator.

Unfortunately, World War II was not about to end that easily. Hitler was in no mood to give up the conquered territory in Poland, or Czechoslovakia, or anywhere else. Welles was fluent in German and needed no interpreter when talking with Hitler, whom Welles found to be ‘dignified.’

On the same day (March 1, 1940) Hitler received a break that would end up leveraging Mussolini. That day, the British had announced that they were cutting off shipments of German coal to Italy. This was a heavy blow to the Italian economy and threw the Duce into a rage against the British – warming his feelings toward the Germans, who promptly promised to find the means of delivering their coal by rail. Taking advantage of this circumstance, Hitler got off a long letter to Mussolini on March 8, which Ribbentrop delivered personally in Rome two days later.

The day before March 1 (February 29—it was a leap year) Hitler had taken the reportedly unusual step of issuing a secret “Directive for the Conversations with Mr. Sumner Welles.” It called for “reserve” on the German side and advised “as far as possible, Mr. Welles be allowed to do the talking.” It then laid down five points for the guidance of all the top officials who were to receive the special American envoy. The principal German argument was to be that Germany had not declared war on Britain and France but vice versa; that the Fuehrer had offered them peace in October and that they had rejected it; that Germany accepted the challenge; that the war aims of Britain and France were “the destruction of the German State,” and that Germany therefore had no alternative but to continue the war. A discussion [Hitler concluded] of concrete political questions, such as the question of a future Polish state, is to be avoided as much as possible.

Hitler received Welles and insisted that the Allied war aim was “annihilation,” that of Germany “peace.” He lectured his visitor on all he had done to maintain peace with England and France.

Remember the pigeon.

“Hitler is taller than I had judged from his photographs,” Welles remarks. “He has, in real life, none of the somewhat effeminate appearance of which he has been accused. […] His voice in conversation is low and well modulated. It had only once, during our hour and a half’s conversation, the raucous stridency which is heard in his speeches–and it was only at that moment that his features lost their composure and that his eyes lost their decidedly “gemutlich” look. He spoke with clarity and precision, and always in a beautiful German, of which I could follow every word […]”

Welles met with Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, the former finance minister who was then out of favor: “He gave me to understand that a movement was under way, headed by leading generals, to supplant the Hitler regime. [….] Dr. Schacht referred to Hitler as the ‘greatest liar of all time,’ and as a genius, but an amoral, a criminal, genius. […] Dr. Schacht further said that the atrocities being committed in Poland were far worse than what was imagined, as to beggar description.”

Again, something familiar-sounding about some of that.

Sumner Welles returned to London on March 10, and argued (in vain) with Chamberlain that the only pathway was disarmament. Welles headed back to Rome on March 15, but the Germans had already made their move to consolidate the Axis. Ribbentrop discussed the Welles mission with Mussolini: “As the Führer had already told the Duce, Sumner Welles’ visit to Berlin did not yield any new elements.”

The meetings that the Nazis held with Mussolini, inspired by the coal embargo and the salvation from Germany, ended up as not a matter of “if” Italy would enter the war, but “when.” An urgent, face-to-face meeting of the dictators was arranged at the Brenner Pass on March 18, and Hitler pressed Mussolini into nominal service to the Axis alliance.

In retrospect, the Germans had been worried that Welles would return from Paris and London with some secret proposal for Mussolini precisely when Germany was gearing up for two major military offensives: the invasion of Denmark and Norway (April 9), and the attack into Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg (May 10) that would lead to the invasion of France.

On July 23, 1940, with Europe falling away, the US was still only testing the waters of public opinion towards engagement. Even the UK, with Germany barking at the door, was still under Chamberlain’s dogma of appeasement. Welles issued the “Welles Declaration” which condemned Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. Roosevelt used Welles’s stronger public statements as experiments that would test the public mood in regard to US foreign policy. Churchill finally changed things in England, while it took Pearl Harbor to engage the US.

And 1940 was not over for Welles, by any means. By September, Welles had resigned in the aftermath of a homosexual scandal involving Welles and two black Pullman car porters on a train from Alabama to Washington.

“Heartline” (2018)

“Heartline” (2018) “Stone Circle” (2014)

“Stone Circle” (2014)

‘Of Dust and Blood (NBM Cover)” (2018)

‘Of Dust and Blood (NBM Cover)” (2018)

“And what, sir, are your intentions…?” (1940)

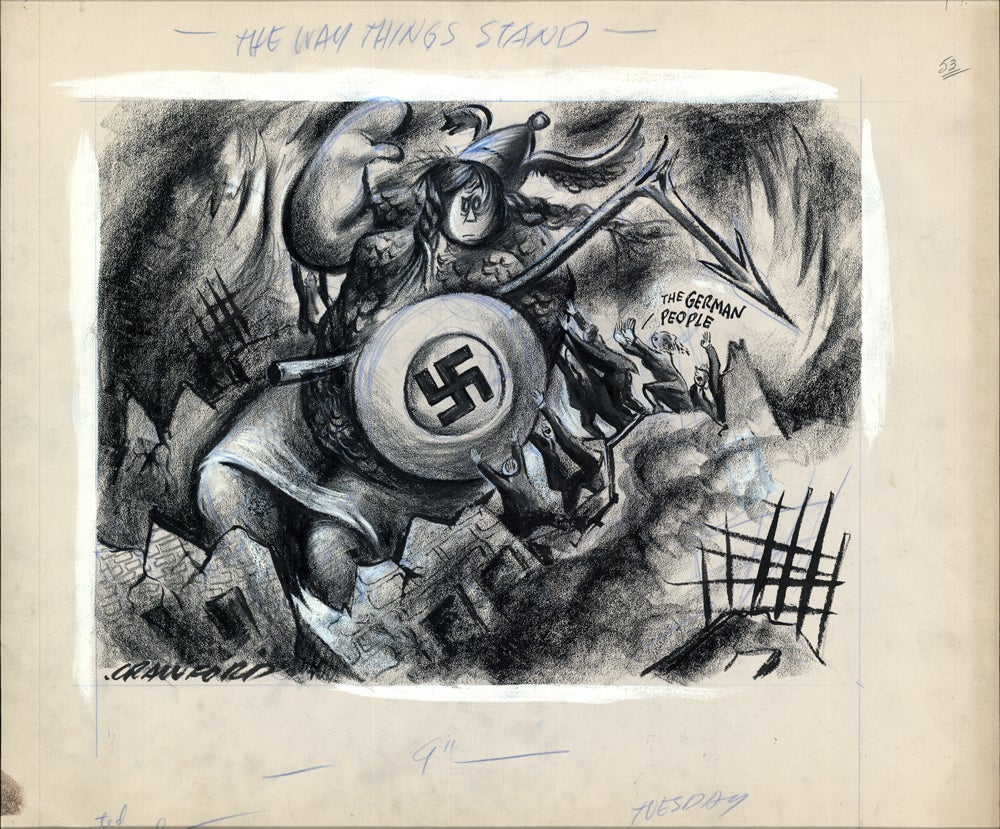

“And what, sir, are your intentions…?” (1940) “The Way Things Stand” (ca. 1940s)

“The Way Things Stand” (ca. 1940s) “The Chemist” (ca. 1950)

“The Chemist” (ca. 1950)

“I Haven’t Lost Anything…” (1965)

“I Haven’t Lost Anything…” (1965)