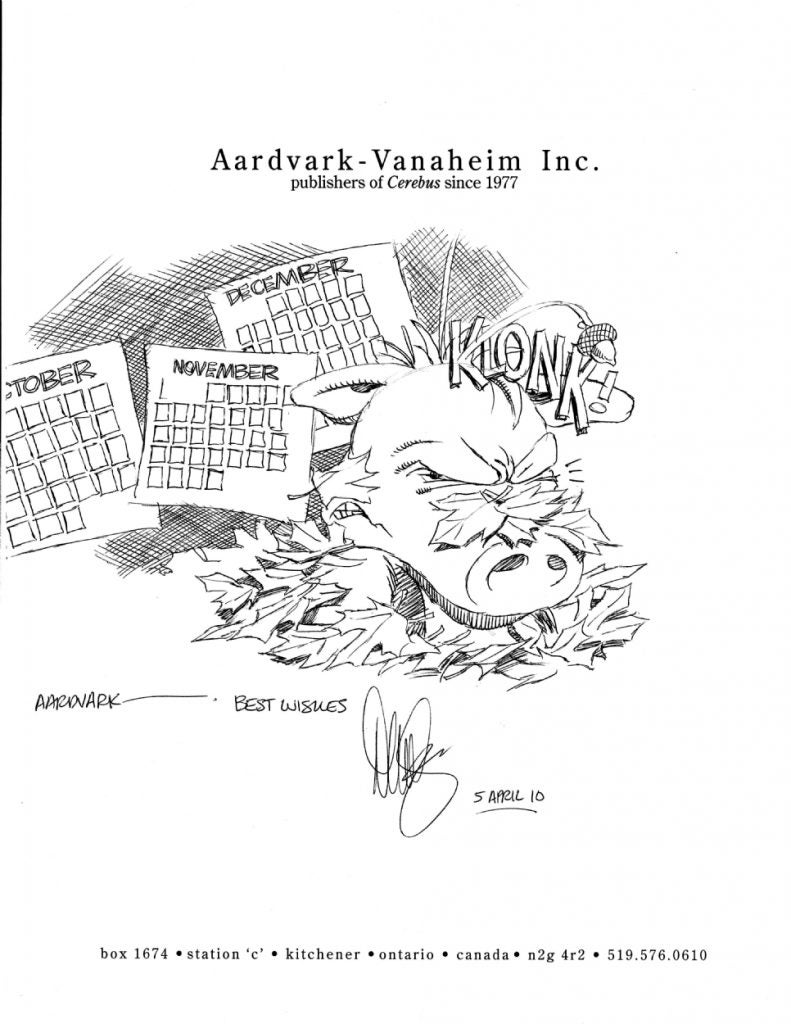

“Charley-Horse Joins the Army” (ca. early 1942) by Jack A. Warren, unpublished

by Jack A. (Alonzo Vincent) Warren (1886-1955)

15 x 20 in., ink on heavy board

Coppola Collection

Jack’s father and step-father were both involved with horses and livestock, and he worked as a cow hand. He met writer and fellow cowboy, Tex O’Reilly (1876-1946), during a horse-buying trip in Wyoming.

In 1901, the 15-year old Warren began to work as an artist at the local newspaper, The Crawfordsville Daily Journal. In 1903, he moved to Des Moines, Iowa, to study at the Cummings Art School. In 1909 he left art school and moved to New York City to seek their fortune as a commercial artist, enrolling at the Art Students League with one of his buddies. Within a year, Warren was working as a commercial artist for The New York Sun.

In 1917 The Century Magazine published a series of stories by Tex O’Reilly about a folk hero, Pecos Bill, a legendary Texas cowboy, whose tall tales were recounted in American popular culture since at least the Civil War.

In 1927 Jack A. Warren and Tex O’Reilly drew and wrote a newspaper comic strip, “Pecos Bill,” for The New York Sun.

The first bi-monthly issue of Adventure Magazine in February of 1935 had a cover painting by Walter Baumhofer of “Pecos Bill Goes Hunting” by Tex O’Reilly. The story was illustrated by Jack A. Warren.

In February of 1935 Loco Luke by Jack A. Warren appeared in New Fun Comics, which was the first American comic book to include original material.

“New Fun Comics,” May 1935, featured Loco Luke on the cover

On July 4, 1935 Jack A. Warren began to draw Loco Luke for the George Matthew Adams Newspaper Syndicate, which also distributed several other strips that had also first appeared in New Fun Comics.

Loco Luke made four appearances in New Fun Comics (February-May 1935), and 2 appearances in Popular Comics (August and October, 1938), under the title “Loco Luke and his Charley Horse.”

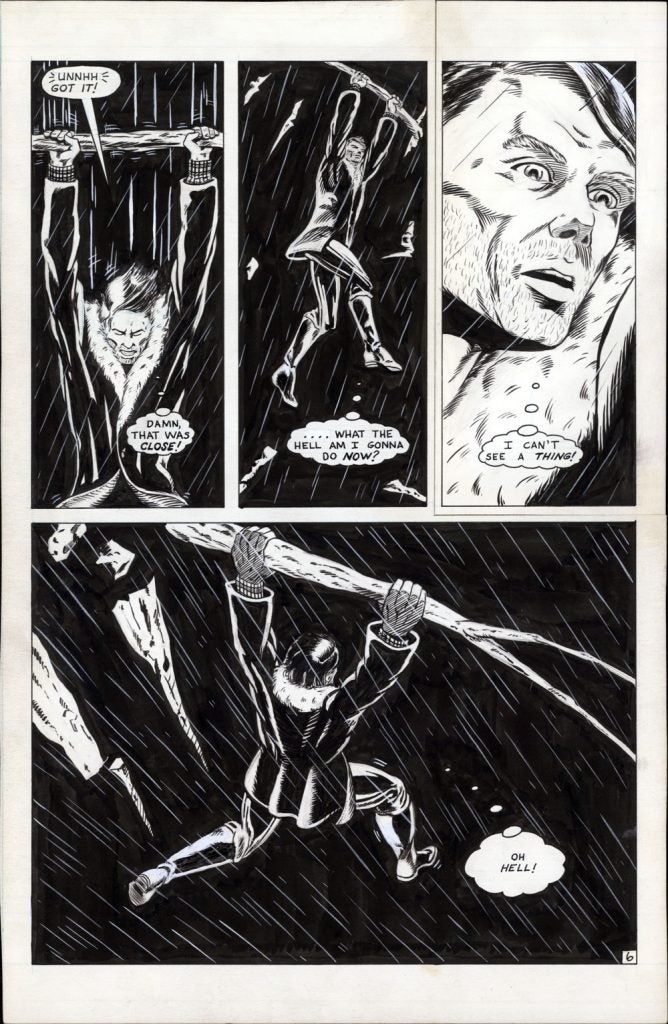

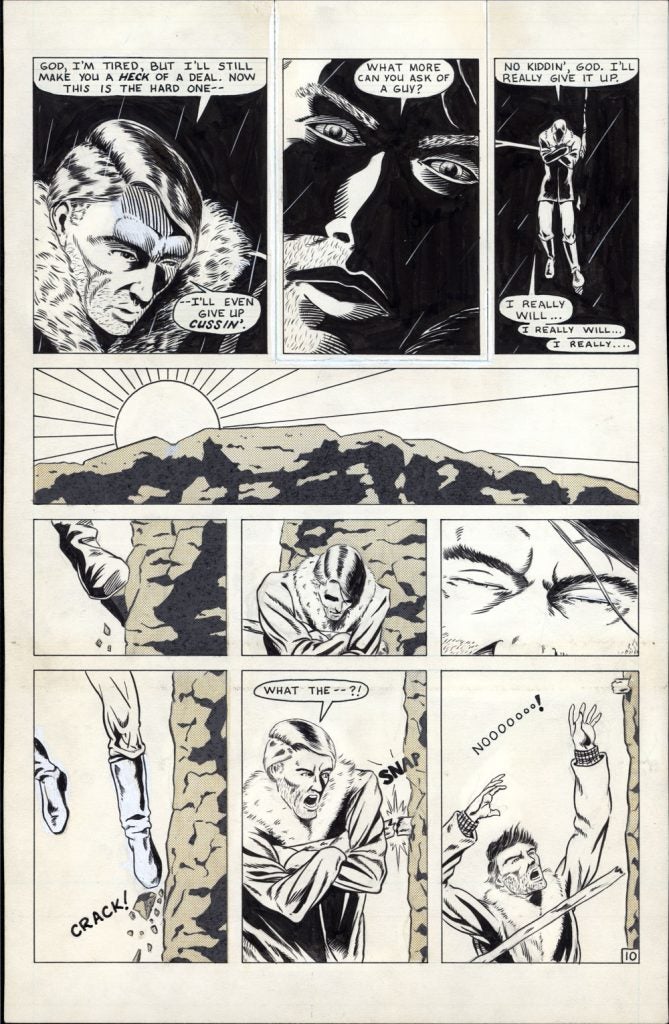

“Popular Comics” #33 (October 1938) p. 55, feature “Loco Luke and his Charley Horse”

“Popular Comics” #33 (October 1938) p. 55, feature “Loco Luke and his Charley Horse”

Loco Luke was a slapstick, zany cowboy strip. It ran in the George Matthew Adams color Sunday section from July 5 1935 to April 4 1936, the entire (known) life of the this experiment in comics publishing.

A “Loco Luke” Sunday strip

When the Sunday section ended, one of only two features to survive was Loco Luke, which was revamped into Pecos Bill, adding Tex O’Reilly as a writer. Unfortunately, Pecos Bill came and went in a hurry.

Between 1936-39, the comic strip “Pecos Bill” by Tex O’Reilly and Jack A. Warren was published in nationwide newspapers by the George Matthew Adams Syndicate. The strip rose quickly to pre-World War II fame and earned Jack a career as a western-genre illustrator and cartoonist.

In 1938, Jack Warren no longer drew the newspaper comic strip “Pecos Bill.” He instead began to draw a different comic strip, “Pecos Pete,” which was not written by Tex O’Reilly, and which ran for 2 years. This was during a squabble over the rights to ‘Pecos Bill.’ It was the same character only he had received a lump on the noggin’, and forgot who he was.

In 1940, Jack moved on into comics. He did several series that were seen in Blue Bolt Comics, such as ‘Krisko and Jasper’ and ‘Spec Pot & Spud’. Warren’s art also appeared in a number of Lev Gleason, Spotlight and Marvel titles.

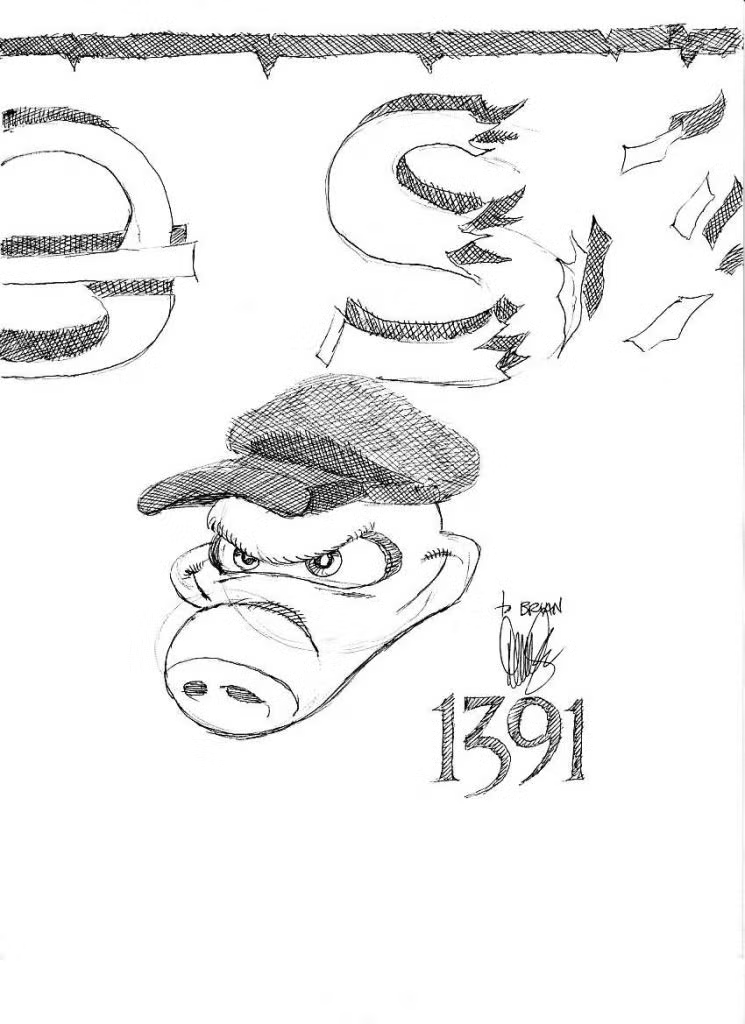

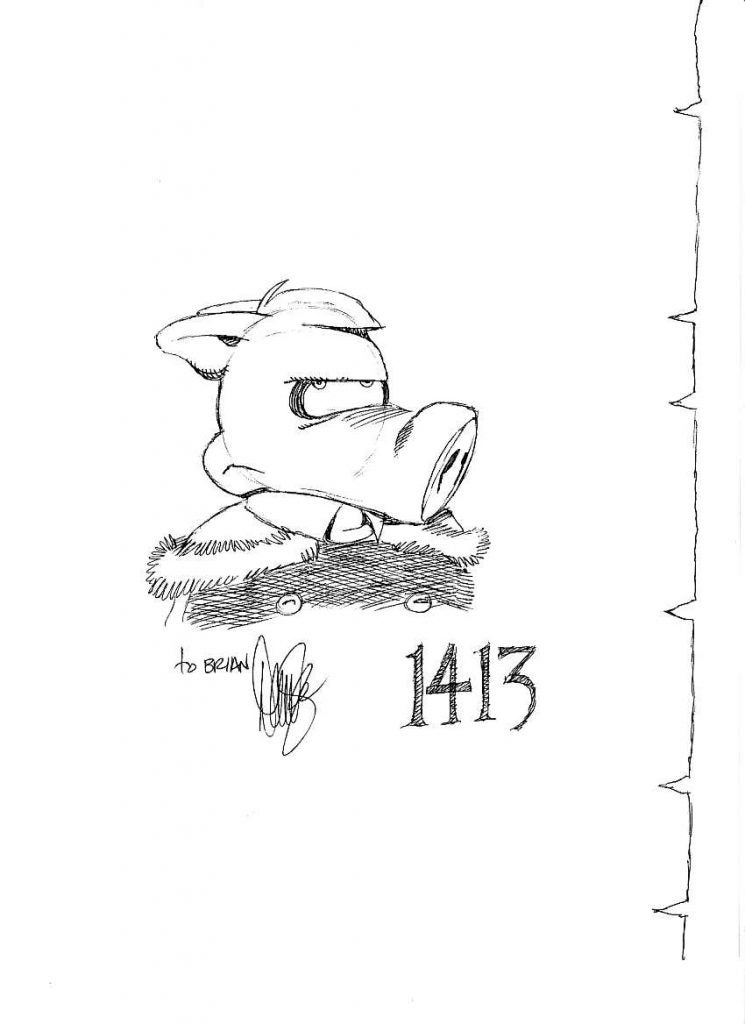

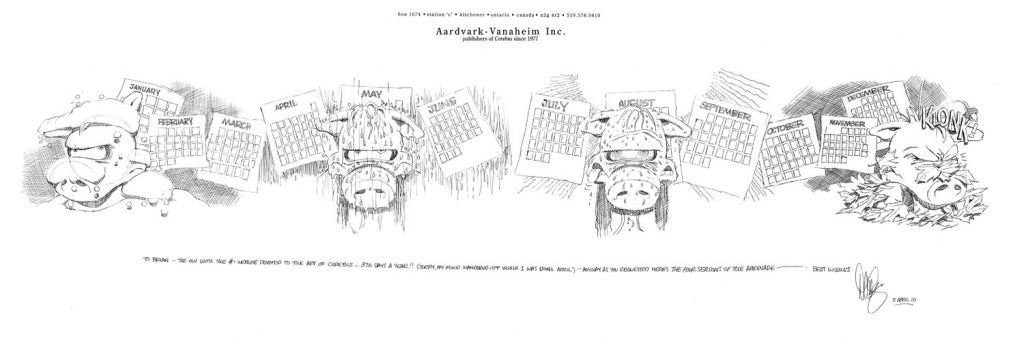

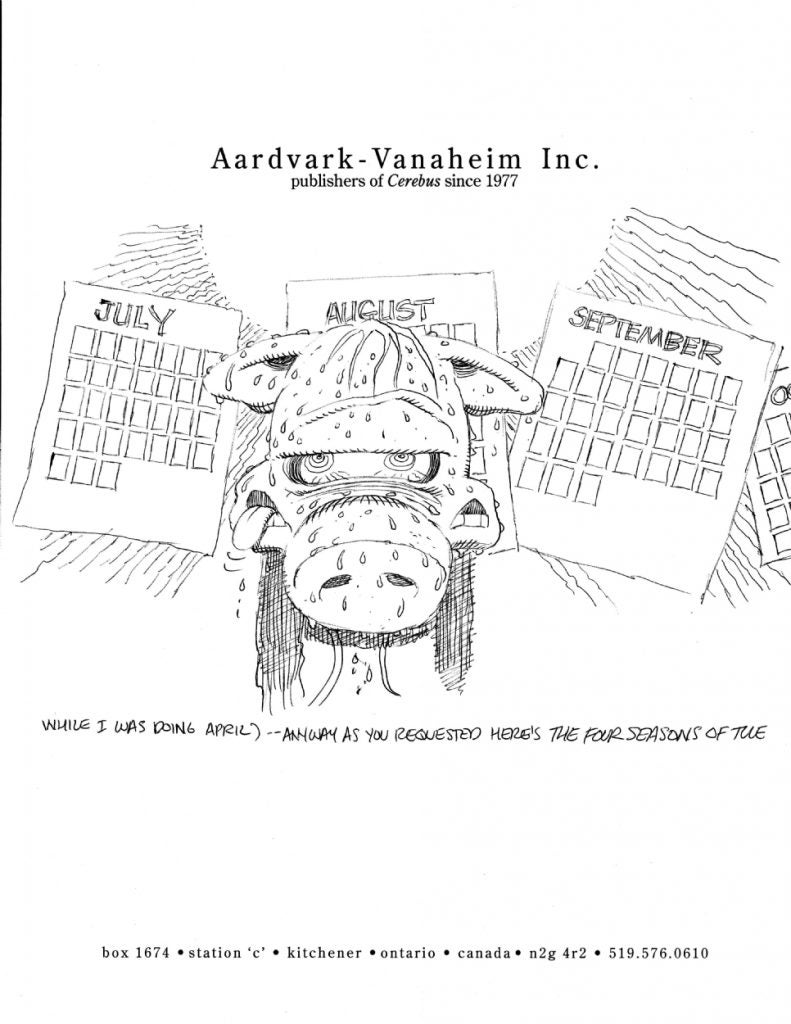

And that brings me to “Charlie-Horse joins the Army,” which was (clearly) never published. The page was drawn and inked, and the dialog put in (pencil). Warren lettered the first few panels and stopped.

A few comments: on the front, the upper left-hand corner indicates that this was meant to be a 5-page story. There is also a notation about “Maldin (sic) Bridge, N.Y.” (Warren and his wife moved to Malden Bridge in 1949). On the back, there is a note that “Richard Kraus mentions Charlie Horse” (Kraus was born in 1923 and graduated as an art major with a bachelor’s degree from City College of New York, ca. 1941, and found early work as an illustrator and editor for comic books and teen magazines. He tried to sign up for the war effort but was found ineligible for military service. He did government intelligence work in Texas during World War II). Warren was in his mid-50s at this point, so past the age for military service.

There is also a notation on the back with the name Willie Lieberson followed by Fawcett Comics, 1501 —, Paramount. Lieberson was the Editor in Chief at Fawcett Comics (located at 1501 Broadway, in the Paramount Building). Fawcett published Thrill Comics #1 (published January 1940 as an ashcan, or copyright holder) featuring Captain Thunder, which was reworked a month later into Whiz #2, featuring Captain Marvel.

One of their comics, Fawcett’s Funny Animals, went on sale in November 1942 (December 1942 cover), and ran until 1964. There would have been at least a 3-month lead time for an ongoing series, and the solicitation for this is likely to have been earlier.

So, if the notations are contemporaneous, I would guess this “Charlie Horse” comic page dates to early 1942, after Pearl Harbor (Dec 1941), given the subject matter, and before Kraus heads to Texas, and (complete speculation) that it was a pitch for the Fawcett Funny Animals book. Charley Horse had appeared twice with Loco Luke, in the 1938 Popular Comics stories, so hearing about a funny animal book might have inspired Warren to revive the horse character. It would be the first page of the pitch, with Charley approaching the soldiers to sign up.

Why did it go unfinished? Did anyone even review it?

Who knows? The topic of the war might not have fit in with Fawcett’s plans for a light-humor book. So early in the US military effort, Warren references a few things from WW1 that would not be true during WW2: there was extremely limited use of cavalry, horses did not draw cannons the way they had 20 years earlier, so the premise might have been deemed as dated.

I have taken the scan of the page, as it exists, into Photoshop, and finished the lettering using copies of Warren’s work on the page.

The unpublished “Charley-Horse” page, lettered.

Thanks to Michael Lancaster (Dirt Road Pictures, LLC., and Calliope), who has contributed a lot of biographical information about his maternal grandfather, Jack Warren, to various internet sites, and for his kind responsiveness to my inquiries.

Tex O’Reilly (1880-1946) – Wikipedia entry

Obscurity of the Day: Loco Luke (May 6, 2013) – Stripper’s Guide

Jack A. Warren – Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

Jack A. Warren – Lambiek Comiclopedia

“Popular Comics” #33 (October 1938) p. 55, feature “Loco Luke and his Charley Horse”

“Popular Comics” #33 (October 1938) p. 55, feature “Loco Luke and his Charley Horse”