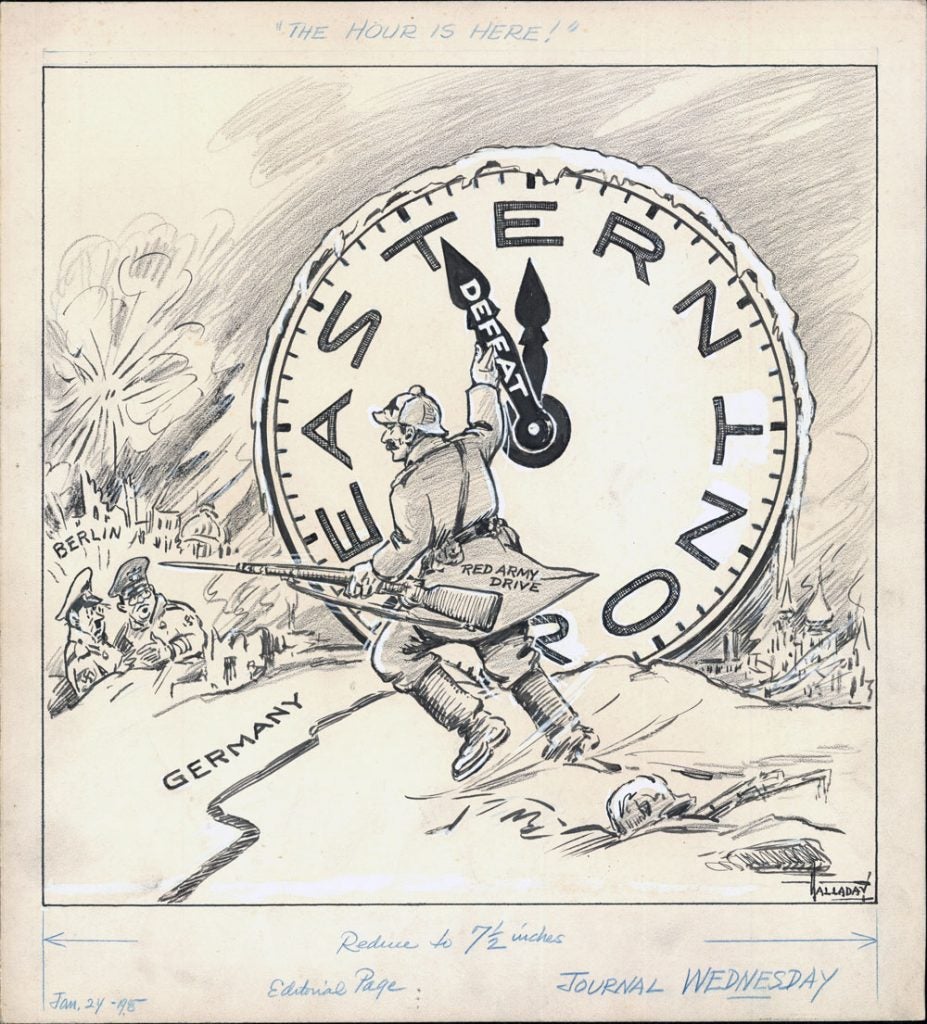

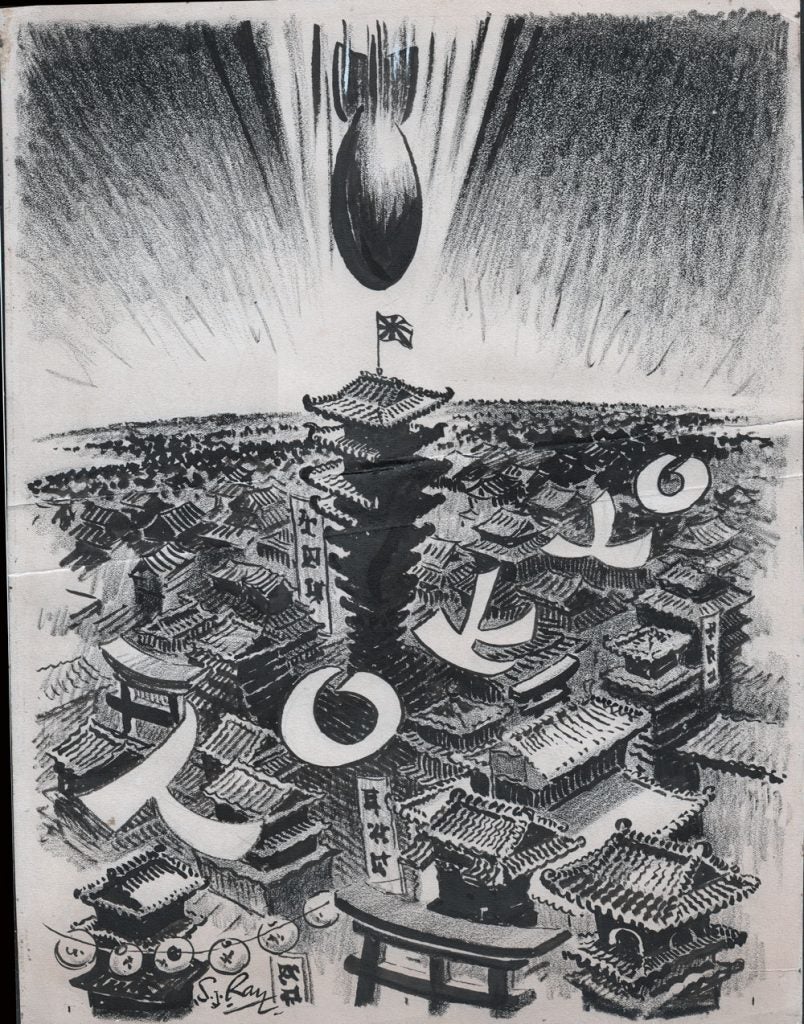

“Wings Over Europe” (March 1, 1933)

by Hugh McMillen Hutton (1897-1976)

14 x 16 in., ink and crayon on heavy board

Coppola Collection

Hugh M. Hutton (1897-1976) was an American editorial cartoonist who worked at the Philadelphia Inquirer for over 30 years.

Hugh Hutton grew up with an artistic mother. After attending the University of Minnesota for two years, Hutton enlisted in the armed forces and served in World War I. Hutton pursued coursework in art through correspondence school, the Minneapolis School of Art and the Art Students League.

He worked at the New York World from 1930 to 1932 and with the United Features Syndicate in 1932 and 1933, drawing illustrations and comic strips. Hutton relocated to Philadelphia and worked as the cartoonist at the Public Ledger in 1933 and 1934. He became the Philadelphia Inquirer’s editorial cartoonist in April 1934, where he stayed throughout his career, retiring in 1969.

Early 1933 is filled with pivotal moments.

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler begins his first government service as the Germany’s Reichskanzier (chancellor), appointed by President Hindenburg.

Many expect him to start fixing Germany’s problems.

On February 1, the new Chancellor declared “More than fourteen years have passed since the unhappy day when the German people, blinded by promises from foes at home and abroad, lost touch with honor and freedom, thereby losing all… Communism with its method of madness is making a powerful and insidious attack upon our dismayed and shattered nation.”

On February 27-28, the fire in the Reichstag was a first step towards Hitler’s dictatorship.

On 27 February 1933, guards noticed the flames blazing through the roof. They overpowered the suspected arsonist, a Dutch communist named Marinus van der Lubbe. He was executed after a show trial in 1934. Evidence of any accomplices was never found.

The Nazi leadership was quick to arrive at the scene. An eyewitness said that upon seeing the fire, Goering called out: ‘This is the beginning of the Communist revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost!’

Before he could go on, Hitler shouted: “There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down.”

The next morning, President Von Hindenburg promulgated the Reichstag Fire Decree. It formed the basis for the dictatorship. The civil rights of the German people were curtailed. Freedom of expression was no longer a matter of course and the police could arbitrarily search houses and arrest people. The political opponents of the Nazis were essentially outlawed.

On March 4, 1933:

Hitler associates Marxism with the mass starvation in the Ukraine, and he associates Marxism with both communists and Germany’s Social Democrats, blurring over the differences between these two groups, while communists were avoiding an alliance with the Social Democrats and calling them frauds and “social fascists.”

FDR took office in the midst of the Great Depression.

Many expect him to start fixing America’s problems.

The next day, March 5, 1933:

FDR closes the banks for a few days.

Hitler’s party wins 43.9 percent rather than the more than 50 percent that Hitler was expecting. He is forced to maintain a coalition with the German National People’s Party. The Nazis begin a boycott of Jewish businesses throughout Germany.

On March 20, 1933, Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s SS paramilitary leader, opens the first Nazi concentration camp, at Dachau.

And on March 23, Chancellor Hitler moves for a vote in the Reichstag that allows him to make laws without consulting the Reichstag – the Enabling Act. He describes the German people as having been a victim of fourteen years of treason while under the Social Democrats and his party, the National Socialists as also having been victimized. He claims that the Social Democrats allowed Germany to be dictated to by foreign powers. He ends his speech saying that “the first and foremost task of the Government to bring about inner consensus with his aims… The rights of the Churches will not be curtailed and their position vis-à-vis the State will not be altered.” The previous jailing of Communist delegates allows Hitler the two-thirds majority he needs for passage, and the President signs it into law.