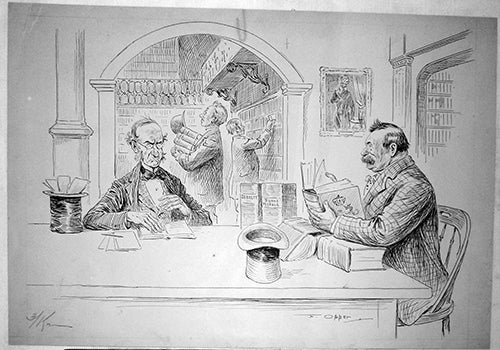

Illustration from Puck(?) ca. 1880-90

by Frederick Opper (1857-1937)

12 x 18 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

I got this inquiry from an academic program director earlier today:

We are concerned because [a student] received a C- in your course without a single progress report getting filed, alerting us to [the student’s] apparent difficulties. We have no concerns about the legitimacy of the final grade, but we are trying to understand what happened, particularly the lack of any red flags to [the student’s] academic advisors to intervene.

I would be grateful for a prompt response to this query.

I do love this question. Here was my reply:

Honestly, “C-” is a passing grade, and [the student] had a C/C- borderline performance throughout the term, and went down a bit on the final, which glued in the final grade. But it could have gone either way.

I would not start even think about making reports unless things are falling under the “D/E” (failing) threshold.

There are no other graded components other than the exams, so the TAs have no access to individual student performances and would not have been in a position to issue any report, regardless.

Much more to the point, though:

I’d be quite interested in following up, sometime, on the benefits and detriments of proactive interventions on the educational experience of our students. The late Professor Emerita Seyhan Ege and I had a delightful and ultimately unresolvable disagreement about this choice, and I miss the lively debate about it since her passing.

We both agreed that the conversation with the faculty member was the most important thing for the student who is in academic trouble… no debate on that. We disagreed on the path.

Seyhan contended that the conversation was the most important thing, so anything to get it to happen was necessary. She wrote personal notes on the exam papers of the students below a certain value, urging them to her office. I have never done this. And I argued that it was detrimental.

I contend that the decision to acknowledge the need for the conversation is the most important thing, so as long as my openness to make appointments and talk is well known, then admitting to one’s self that the appointment is necessary is a significantly more long-lasting educational lesson, in the long run, than the conversation itself.

Seyhan and I agreed that there were students we were each throwing under the bus because of our position. Some of her students lost the rare opportunity to learn how to self-regulate, while at the same time others benefitted from the interaction in her office. I sometimes see students who finally show up – yes, in desperation – and then who end up kicking themselves for not having come in earlier (remember the last line spoken by the Deanna Troi character in the ST:TNG finale, ca. 1994… “You were always welcome.”).

Anyhow, it’s a great topic.

I know this program director well, so I was not at all worried about opening this debate. The response:

You raise really important questions, which is partly why I am pursuing this. I’m interested in figuring out how effective long-term support (as opposed to just ensuring students get good grades) might get provided. My query was prompted by the fact that in this particular student’s case, not a single red flag was raised, in courses across the curriculum, although in retrospect it’s clear they should have been. We might reasonably disagree on where to draw the line of concern; maybe it’s my weak-kneed social-science/humanities attitude that anything below B- is a concern, but that’s a minor quibble.

The bigger issue is exactly about proactive interventions. So let’s revisit that question over coffee sometime.

In reply, I could not help but make sure the point was being made:

I am 100% sympathetic to the dilemma, particularly the unasked question.

Why wasn’t the student at my door… at your door… at the advisors’ doors… if the situation was so uniformly dire? My own concern is that the student’s instructors were the second-most important people who were not raising red flags. [The student], to me, is the first most responsible and has not yet learned that.

“But officer, I speed all the time and no one has ever pulled me over, so I thought it was OK.”

Or, is this really about someone who does not know how to swim – and does not know that they do not know, because they see everyone around them swimming just fine – and jumps into the deep end, figuring that surely, if I start to drown, someone will notice and rescue me.

“The Great Stone of Sardis” (1897)

“The Great Stone of Sardis” (1897) “In the Parlor” (tent) 1895

“In the Parlor” (tent) 1895

Opening up my curmudgeonly bag for a moment (does not seem like this image would imply that, would it?).

Opening up my curmudgeonly bag for a moment (does not seem like this image would imply that, would it?).

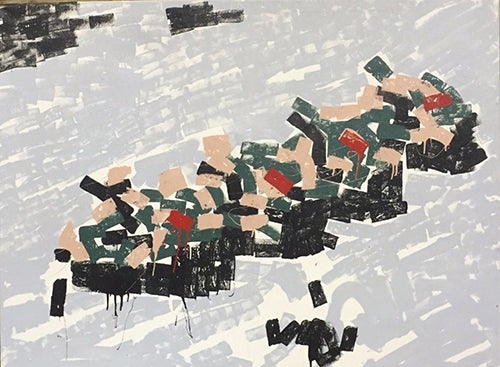

“Tank Man” (2015)

“Tank Man” (2015)

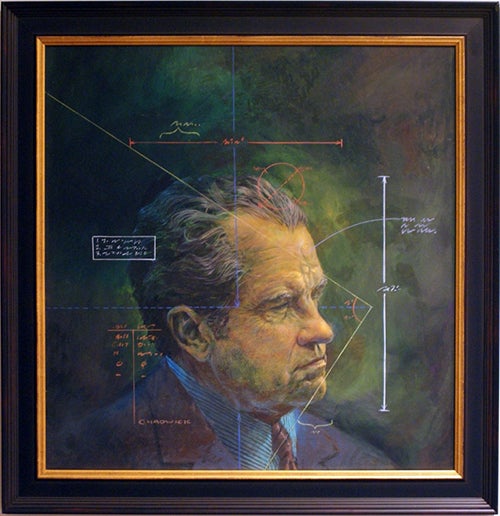

“Richard Nixon Portrait” (ca. 1978-79)

“Richard Nixon Portrait” (ca. 1978-79)

“Still Life with South Korean Bowl with Asian Pears” (2017)

“Still Life with South Korean Bowl with Asian Pears” (2017)

“Blood Moon” (2016)

“Blood Moon” (2016)