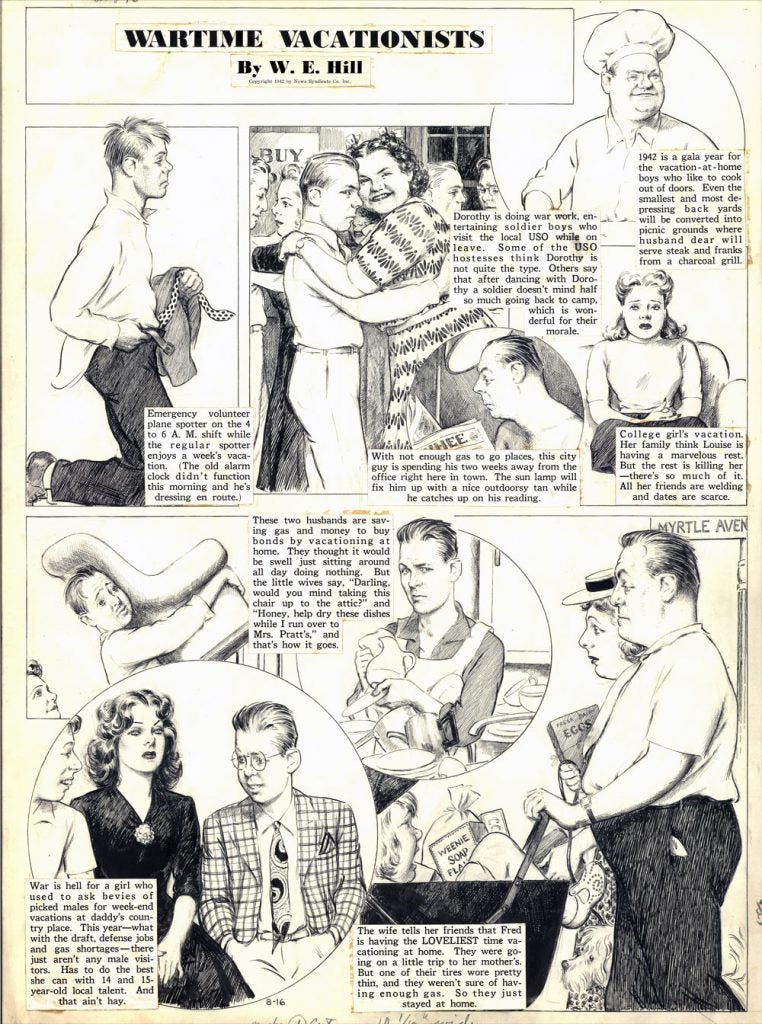

“Say A-Ah…” (May 25, 1945) 1/17

by Frederick Little Packer (1886-1956)

14 x 22 in., ink on heavy paper

Coppola Collection

Packer worked at the LA Examiner from 1919-1931, and then moved to the New York Daily Mirror in 1932.

His cartoons and posters for the World War II defense effort earned him citations from the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize on May 5, l952 for his Truman Cartoon, “Your Editors ought to have more sense than to print what I say,” which appeared in the “New York Daily Mirror” of October 6, l951.

In August 1953, he was invited by the Library of Congress to make a gift of his original drawings to its permanent collection.

The campaign for some form of universal government-funded health care has stretched for nearly a century in the US. On several occasions, advocates believed they were on the verge of success; yet each time they faced defeat. Remarkably, the conservative lobby uses the same argument every time: the programs are a slippery slope towards institutionalized socialism.

Between 1906-1915, the “American Association of Labor Legislation” and the “American Medical Association” partnered on a bill. Rallying against it: the AFL repeatedly denounced compulsory health insurance as an unnecessary paternalistic reform that would create a system of state supervision over people’s health. They apparently worried that government-based insurance system would weaken unions by usurping their role in providing social benefits. The commercial insurance industry was also opposed. This effort came to an end when the US entered WWI and anti-German fever rose. The government-commissioned articles denouncing “German socialist insurance” and opponents of health insurance assailed it as a “Prussian menace” inconsistent with American values.

The Great Depression did not help for passing compulsory health insurance in the US. With millions out of work, unemployment insurance took priority followed by old age benefits. The FDR administration feared that including health care would jeopardize the entire Social Security legislation.

The Wagner National Health Care Act (1939) was introduced after the 1938 election put a resurgence of conservatives into office, and it died on the vine. Interestingly, a version of it was introduced for the next seven years.

The next major attempt, in 1943, was the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill. Although there was always a lot of debate, the coalition of organized labor, progressive farmers, and liberal physicians were constantly red baited as supporting socialist ways.

After FDR died in 1945, and Truman became president, the health care issue moved into the center arena of national politics and received the unreserved support of the new president. But the opposition had acquired new strength in the post-war world. Compulsory health insurance became entangled in the Cold War and its opponents were able to make “socialized medicine” a symbolic issue in the growing crusade against Communist influence in America.

On May 24, 1945, Wagner introduced, with Senator Murray, S. 1050, entitled “The Social Security Amendments of 1945.” The bill provides for “the national security, health and public welfare.” Representative Dingell of Michigan introduced a companion bill (H. R. 3293) in the House at the same time. Wagner: “I particularly invite your earnest study of the provisions of the bill relating to health. There is absolutely no intention on the part of the authors to ‘socialize’ medicine, nor does the bill do so. We are opposed to socialized medicine or to state medicine.” The bill never made it out of the Senate.

In 1945, the AMA spent $1.5 million on lobbying efforts, which at the time was the most expensive lobbying effort in American history. They had one pamphlet that said, “Would socialized medicine lead to socialization of other phases of life? Lenin thought so. He declared socialized medicine is the keystone to the arch of the socialist state.”

The birth of the People’s Republic of China (1948), the growing threat of the Soviet Union, the Korean conflict and the backdrop of the McCarthy era, all combined to kill national health care as an issue until the focus on the elderly emerged as an action item in LBJ’s New Society, resulting in Medicare and Medicaid (1965).