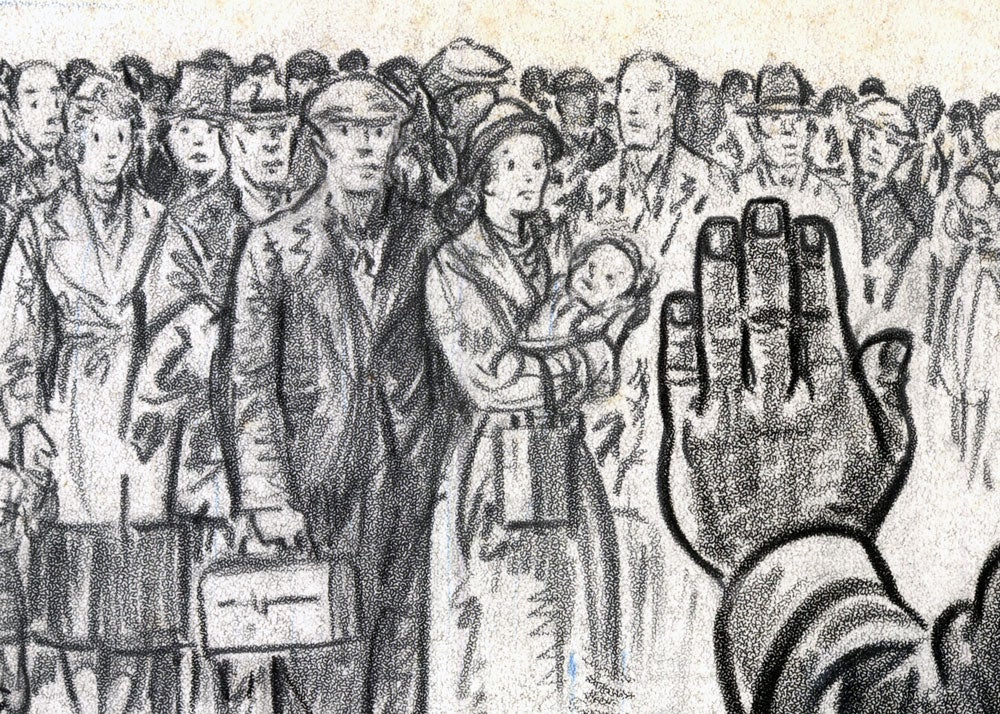

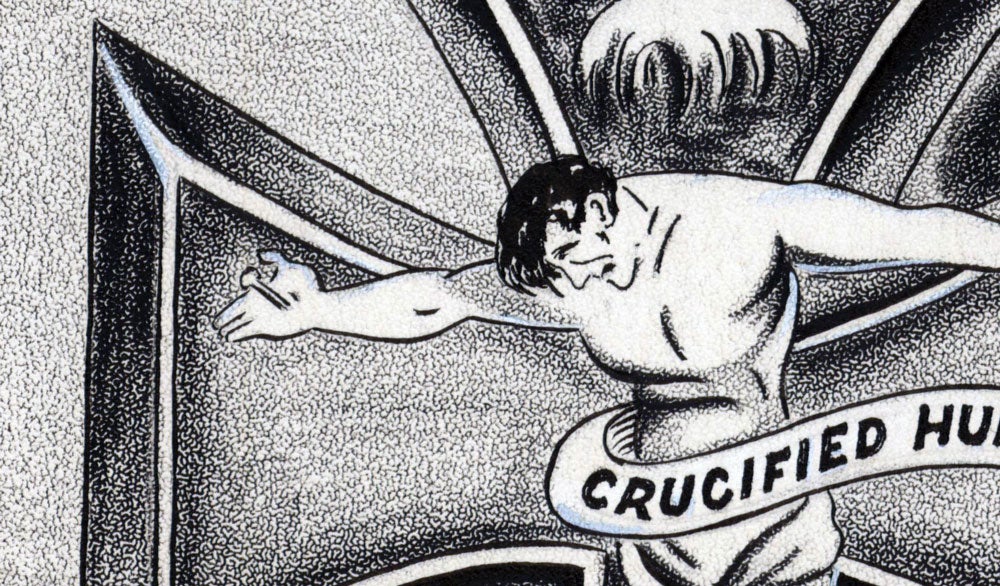

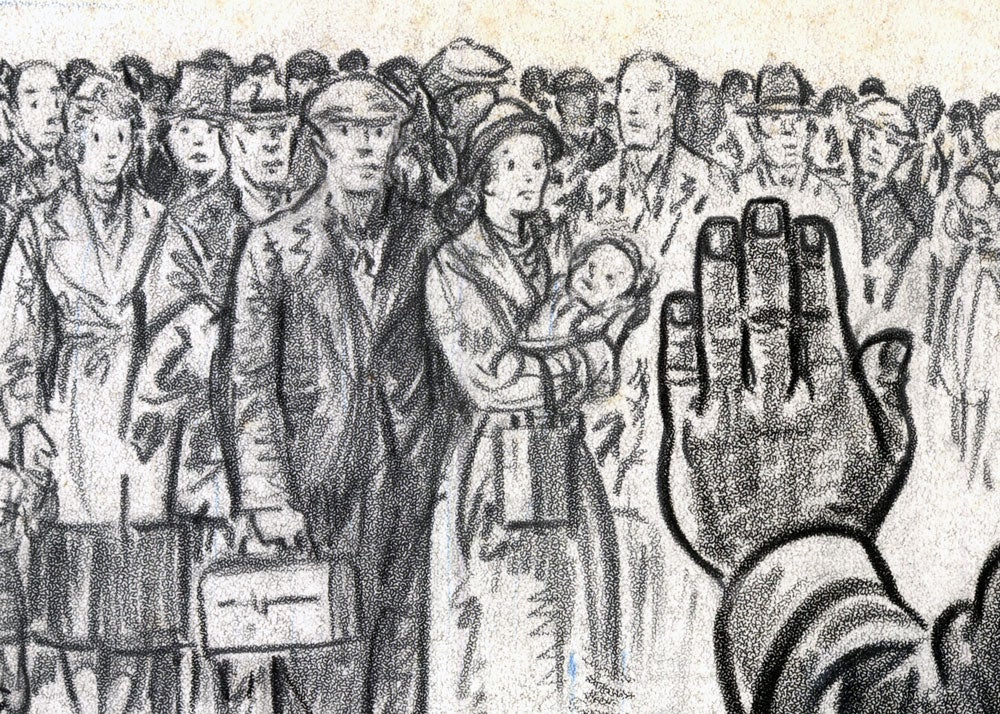

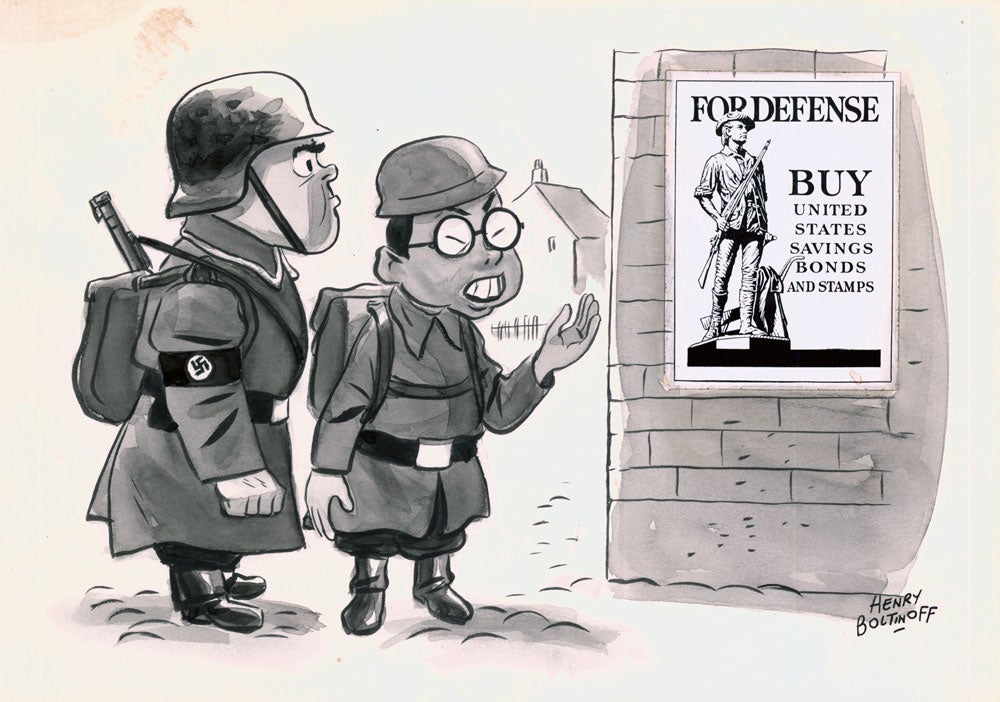

“The Disenfranchised!” (undated)

by Burris A. Jenkins, Jr. (1897-1966)

14 x 22 in, ink wash and crayon on board

Coppola Collection

Burris Jenkins Jr. was the son of a prominent Kansas City minister, war correspondent and newspaper editor. Jenkins Jr. was a popular sports cartoonist, whose work appeared in the New York Journal-American from 1931. His humorous published verses were also popular. Although best known for his sports themes, Jenkins was also a skilled courtroom illustrator and editorial cartoonist.

Jenkins was not afraid to provoke, and he has some strong WW2 examples, including one of the rare direct commentaries on concentration (death) camps. Among his best-remembered cartoons are his angry piece on the discovery of the dead Lindbergh baby, and his sentimental image of Babe Ruth’s farewell to Yankee Stadium.

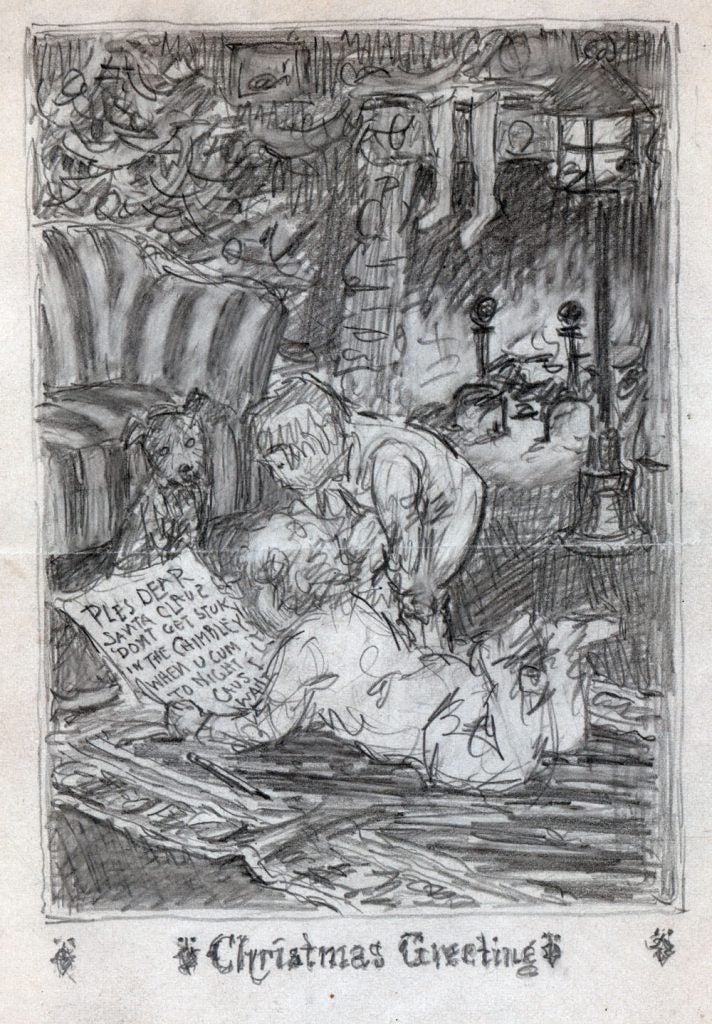

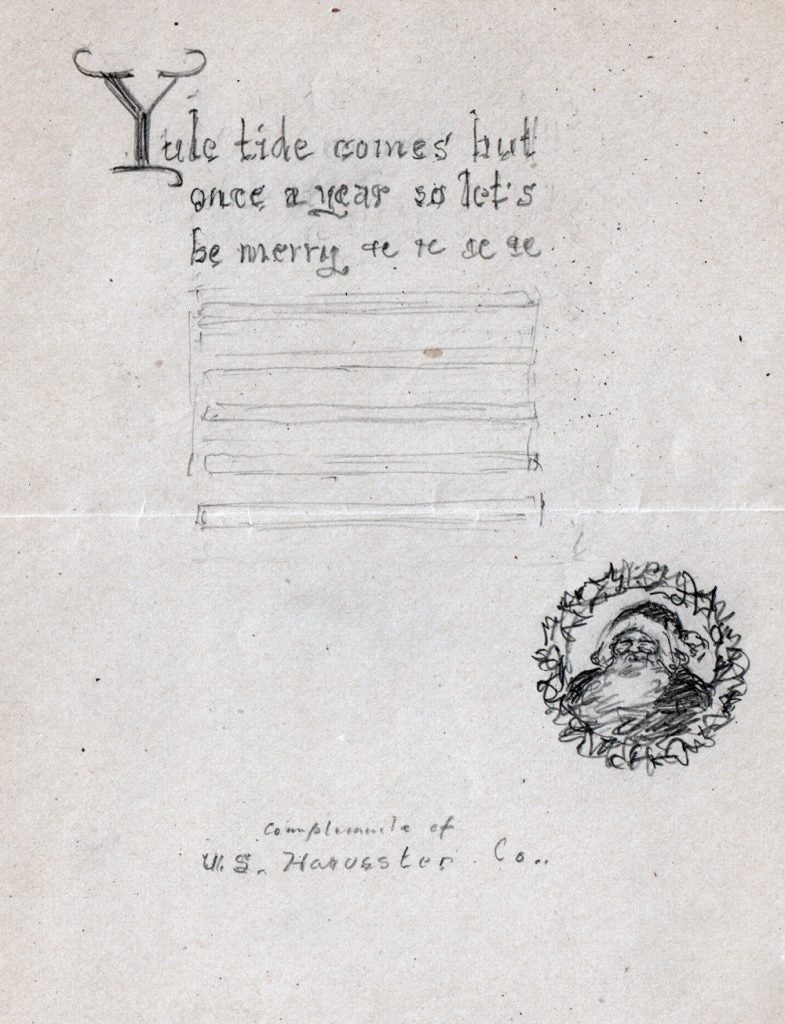

He was fired from his first job at the Kansas City Post for a series of pessimistic Christmas cartoons, a firing that prompted his father’s resignation from the same newspaper.

His father was an interesting guy. Jenkins, Sr (1968-1945) was ordained in 1891 and served as a pastor in Indianapolis. He received advanced degrees from Harvard and went on to serve as a professor and president of the University of Indianapolis and president of Kentucky University. He left Kentucky to return to Kansas City as pastor of the Linwood Boulevard Christian Church. The church burned in 1939, and Jenkins chose Frank Lloyd Wright as the architect for the church’s new home overlooking the Country Club Plaza.

Jenkins served as editor of the Kansas City Post from 1919 to 1921, hoping to fight for the establishment of the League of Nations. The Jenkins, Sr., biography tells the story about his leaving the Post slightly differently that for the son: “After two years, it became necessary for him to choose between the newspaper and his pulpit and, without hesitation, he resigned from the Post.”

“Live dangerously!” Jenkins would thunder from the pulpit, embracing his own philosophy against all adversaries. Unconventional in nearly every aspect of his chosen field, Jenkins often preached from non-Biblical texts, such as the latest book or his travels abroad. The church frequently hosted motion pictures, dances, card games, and fundraising boxing matches. These activities led to opposition to Jenkins and his Community Church from other churches in the city.

Citizens without time enough to vote.

Disenfranchisement has been around longer than the right to vote, and as voting rights were granted, the ante was upped to continue to find disenfranchisement methods.

Literacy tests, poll taxes, and extensive residency requirements were used to disqualify black and poor white voters. In 1944, for instance, the Supreme Court struck down the use of state-sanctioned all-white primaries by the Democratic Party in the South. States then developed new restrictions on black voting; Alabama passed a law giving county registrars more authority as to which questions they asked applicants in comprehension or literacy tests.

For years, you could only vote on Election Day, hence the cartoon commentary, as lots of working people were excluded.

Early voting is relatively recent and not at all universal. Early voting in person is allowed without excuse required in 33 US states and DC. Absentee voting by mail without excuse is allowed in 27 states and DC. In 20 states, an excuse is required.